TYPHOON PROOF An Ivatan house, constructed with mortar and cobbles, has walls as thick as one meter and concrete slabs for roof. Narrow doors and windows are designed against strong winds. CONTRIBUTED PHOTO

Batanes, the northermost part of the country, lies in the path of most of the 20 or so tropical cyclones that enter the Philippine area of responsibility every year.

Without a background on the Ivatan, the people of Batanes, one could hardly imagine how they live with the impact and continuing threat of tropical cyclones; how their houses and crops could resist strong winds.

But the Ivatan learned to live with cyclones. There are extant proofs that they have long known about disaster risk reduction and management, at least in dealing with typhoons.

TORN OFF A boy sits on what used to be the roof of a house damaged by Supertyphoon “Yolanda” in Barangay Baras, Palo, Leyte. RAFFY LERMA

They designed and constructed houses that could withstand winds blowing at least 250 kilometers per hour, now dubbed supertyphoons.

Agriculture is regulated by adopting wise land-use practices.

Root crops

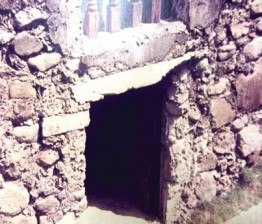

ENTRANCE to lower ground floor where root crops and other essential food items are kept. In another section, livestock are sheltered during bad weather. CONTRIBUTED PHOTO

The high frequency of storms passing through Batanes and the difficulty of transporting rice and other commodities from the mainland taught the Ivatan to tap root crops, which can be grown in spite of strong winds, as their staple.

Rice, bananas and other plants are grown but in the leeward side of fields. Cattle and other livestock are also bred and raised on the islands.

Houses, particularly the old ones, constructed with cobbles and mortar, have walls as thick as 80 centimeters to one meter.

Concrete slabs

Roofs are made of concrete slabs or cogon. The thatch, usually 30 centimeters thick, is protected with fishing nets or bamboo trellis against strong winds during the typhoon season. A cogon roof lasts more than a decade.

Doors and windows, made of hardwood planks, are exceptionally narrow and short compared with those of standard houses. For bolting doors and windows, hardwood bars are used.

Large kitchens

The kitchens of most typical Batanes houses, built separate from the main structures, are exceptionally large compared with ordinary houses elsewhere in the Philippines.

In many kitchens, one would find bundles of dried fish, garlic and onions, and in some houses, earthen jars hanging above the stove areas. The jars contain palek, the native toddy from sugarcane.

Food storage

INTERIOR of an Ivatan kitchen and storage structure. Note stocks of dried fish, onions and garlic. Stored elsewhere are root crops. CONTRIBUTED PHOTO

Almost every family in the community stores large supplies of food and other household needs that can last for days, even weeks, as preparation for harsh weather that the Ivatan are very much aware of and have learned to live with.

Especially designed houses of affluent Ivatan consist of two rectangular two-story structures connected by an open concrete platform.

One of the structures is divided into a living room, a dining area and a kitchen. Its lower ground floor is used for storage of root crops, like camote, cassava, ube, firewood and other household materials.

Sleeping quarters

The second structure serves as sleeping quarters and bathroom. Its lower ground floor is for securing livestock during bad weather.

And so, it is in Batanes, where tropical cyclone disaster is virtually unknown. Batanes, indeed, could very well be a model community for tropical-cyclone mitigation and preparedness.

(This article is an appendix to Chapter 3, “Surviving from the Wrath of Scourging Winds,” of a forthcoming book, “Stop Disasters: A Handbook on Natural Disaster Risk Reduction,” by Rolando G. Valenzuela, MNSA. A former seismologist at the Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration, he used to be into “chasing earthquakes” as far as the Canadian Baffin Island at the Arctic Circle, near Greenland.)