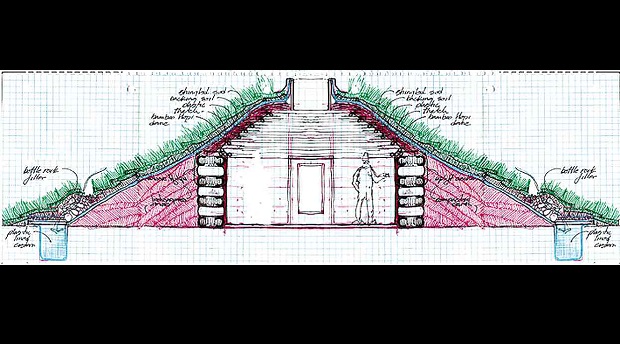

A ROUGH sketch of a biotectural design for a windproof structure. Photo from https://earthship.com/philippines

It’s been more than a month since disaster struck central Philippines. While relief operations are still ongoing, the slow rebuilding process is, or will soon be at hand. People who have closely watched the news and read the articles have probably heard of how this should be handled. There is a lot of good information to be taken from them.

My worry is that, from what I’ve seen so far, they have been very acute—specifically written with Leyte and Supertyphoon “Yolanda” in mind. That is not without good reason. But after immersing ourselves with this information and recent events, it’s easy to lose sight of the fact that there is a bigger picture to consider.

Ring of Fire

We’ve always been a country constantly beset by natural calamities. One big reason is our inclusion in the Ring of Fire, an area around the Pacific Ocean prone to a large number of earthquakes and volcanic eruptions. (See map.)

The second reason is very fresh in our memories. A large number of storms, perhaps the most out of all other countries, pass through the Philippine area of responsibility. In some ways, we also act as a cushion for neighboring areas, such as Hong Kong, Taiwan and Vietnam.

This predicament is not new to us. But why is it that it feels like we have never felt so vulnerable to disaster until recently? I believe most of it has to do with the intensity of these recent typhoons. Five out of the 10 cyclones with the highest death tolls ever to hit the country occurred within the last 10 years. This also correlates with the cost of rebuilding the damage these typhoons inflicted.

Reports vary, but Yolanda is on track to becoming the costliest typhoon in Philippine recorded history in terms of damage to infrastructure and agriculture. [Using UN’s definition of loss and damage, government placed the total cost at P571.1 billion, of which P325 billion was in housing.]

Times a (climate) changing

I believe that we have to come to terms with the fact that our climate is no longer quite what it used to be. It’s become harsher. Dry seasons have seemingly become hotter. The wet seasons bring harder rain, which unfortunately comes in the form of violent storms, at times.

Nature has undoubtedly changed the playing field. Are any of us confident that a typhoon the scale of Yolanda will never hit us again? Can anyone be sure it won’t happen again next year? Never mind the climate change debate and what may or may not happen 20 to 25 years down the road. We’re already facing big problems right now. And we have to find ways to deal with it.

Perhaps for some, this will be a callous thing to say, but one thing Tacloban and other areas in the Visayas have going for them is that they have the opportunity to start from scratch. Limited resources aside, the field is wide open, so to speak. And already, we hear a lot of people telling us all sorts of things, pointing out all the wrong things that happened and how they are to be rectified.

When relief operations wrap up, the slow and painful rebuilding process will go full swing. Determining the right way to do it will undoubtedly be awfully complicated as there are so many things to consider.

VENICE gates against storm surges. Photo from https://class.coursera.org/designingcities-001/lecture/33

Holistic

When I was a kid, one of the most important lessons my dad ever taught me was that no man is an island—a truth I realized time and again as I grew older. As a graduate student, I learned that the same lesson applied in environmental science.

We were taught that solutions to any environmental issue required an analysis of multiple aspects that inevitably relate to each other. This is the so-called holistic perspective which we hear about regularly, but may not necessarily understand. (See Venn diagram of sustainable development.)

Resistance, resilience

There are two attributes to keep in mind when talking about ecological stability: resistance and resilience. This is a very interesting discourse especially with all the different meanings they connote. But for now, I’ll keep it simple and treat them as two different attributes.

There are few things that can explain resistance and resilience more succinctly than that parable of the acacia and bamboo trees. In the face of a strong wind, the acacia stands firm and tall, while the bamboo bends and sways accordingly.

Think of resistance as the ability to continue to function normally despite disturbances. I’ve seen comments and articles through social media advocating how effective it would be to have bomb shelter-like buildings for evacuation centers instead of the usual low-cost multipurpose halls in saving lives. These friends of mine are thinking about resistance against extreme conditions. It’s a good idea. It would also seem that resistance is usually the first thing that comes to mind among people in Yolanda’s wake.

Ability to adapt quickly

Resiliency is an interesting term, but sometimes misunderstood. I also don’t understand how some people scoffed at how people around the world referred to us as being resilient. It doesn’t assure walking out of any disturbance or adversity unscathed. But if you do survive, it gives you the ability to recover and adapt quickly and effectively in the aftermath, like the bamboo that reassumes its normal position after a strong wind. You go down like the rest of the afflicted.

Resilience makes recovery easier and perhaps even helps develop resistance against the same disturbance in the future. In severe adversity such as being in the middle of the strongest typhoon in written history, resistance is nearly futile. It’s the recovery process where you can do something. And it is never a bad thing to be good at that.

Of course, it is ideal to excel in both attributes. Sometimes they go hand in hand. But like everything else in life, the reality is that you can’t have them all. We also have to understand that one is not necessarily better than the other. Resiliency isn’t worth anything if you don’t survive in the first place. But what use is survival if you can’t adjust to any new condition or predicament introduced in the wake of a disturbance.

Rebuilding the right way

The problem with figuring out what should and what should not be done is that there are so many things to consider. Conventional fast-track rebuilding may no longer be a good medium to long-term solution. We’ll just keep on repeating the process and waste a lot more resources in the long run. We need to take a long hard look and study the predicament we’ve found ourselves in.

I do not subscribe to the school of thought where the government is blamed for everything. Hurricanes “Katrina” and “Sandy” in 2004 and 2012, respectively, illustrate how a mix of government complacency and sheer force of nature can render even the most powerful of nations helpless. Imagine what would have happened to New Orleans and New York had both been Category 4 as Yolanda (aka Haiyan) was. However, I do concede that they play a crucial role in facilitating the rebuilding process.

No-build zones

While it does seem like another one of those knee-jerk reactions, barring the construction of an elaborate and expensive series of gates and barriers, declaring coastal areas “no-build zones” is arguably as good a first move as any. It was obviously meant to keep safe against tsunamis and storm surges.

But what the news and the politicians didn’t seem to have mentioned is that in the long run, it will also serve as leeway against rising sea levels. While the amount of protection it can provide against tsunamis and surges is a point of debate, the rehabilitation of mangrove areas will potentially be a boon for biodiversity. And with little or no occupants along the coastal zone, waste management may also become easier. One can only hope that all these benefits are worth the cost they entail, as property and livelihood will inevitably be affected.

New city designs

Venice employs a series of floodgates to protect itself from surges. (See Venice gates photo.)

This may as well be an opportunity to explore the employment of new city designs and infrastructure. Perhaps now more than ever, finding ways to work with nature and not in spite of it is important. This will undoubtedly pose its own set of challenges. That is why developers must be given a good reason to go ahead with this.

Green building movement

Sustainability has always been one of the main selling points of the green building movement. It also addresses more mundane parameters, like heat, lighting, acoustics and ventilation.

But with recent tragedies still fresh in our memories, this is a good opportunity for the movement to gain more traction. Green building designs have to be able to prove that it can be of benefit in extreme conditions. Buildings need to handle rough environmental conditions, or at least help ensure the safety of their occupants when they reach breaking point due to the sheer strength of a disturbance, like earthquakes, torrential rain, floods, and yes, storm surges and 270-kph gusts that mercilessly pummeled the Visayas.

Stone house, biotecture

Traditional designs such as the stone houses of Batanes and the use of stilts have been highlighted as solutions. Experts have also weighed in as to how typhoon-resistant buildings ought to be built. I think these are good ideas, but are by no means the only ones we have available.

In mainstream media, I have yet to see people talk about the possibility of incorporating information and communication technologies, which have been proven elsewhere to be invaluable in disaster risk reduction and environmental management. It would also be good to see farther out-of-the-box thinking like getting into biotecture. (See biotecture illustration.)

Individually, they may or may not be appealing or even plausible for people. But in the case of the latter, perhaps the best possible plan can be formulated by somehow incorporating the best elements from all available ideas.

All in this together

We will have the usual excuses. I have heard and read them—we don’t have the resources or we have a corrupt government run by either self-serving or downright weak-willed and incompetent people. Or maybe what we come up with is just plain unrealistic for any other reason.

True enough, even the soundest of plans and designs won’t mean squat in the face of substandard materials and spotty execution—things popularly associated with unscrupulous private parties and government corruption.

Laying blame is sadly commonplace. But the truth of the matter is that we as individuals must own up to a certain amount of accountability ourselves. Even more importantly, we have to understand that no matter how good a master plan turns out and even if the government does its part, the whole thing won’t succeed without public support.

Interrelationships

Nature is a network of interrelationships wherein we are an important entity. For that to happen, we have to be educated. This may well be the most important thing above everything else. Thanks to social media and open information, it has never been easier to arm ourselves with all sorts of knowledge.

The challenge is to separate what’s useful from what’s not. That is what still makes educational institutions relevant. Open education resources and massive open online courses touching on the things I have mentioned abound, ripe for the picking with no strings attached.

Media

Even though recent events have sullied their general reputation, nongovernment organizations also excel at bringing the knowledge to the people who otherwise would not be able to attain them on their own. And of course, there is mass media. It is still arguably the best means of dissemination to the largest audience and wielding enough credibility for people to heed.

Yes, the whole thing is complicated and will very likely take a long time, a significant amount of resources and a high level of coordination to achieve. I am also sure that there are even more facets which I have failed to cover. Nature is not a closed system. If we want to learn how to work with it best, there is no avoiding it—we have to take a holistic approach going forward.

(Al Francis D. Librero is a member of the faculty of University of the Philippines Open University. He is a generalist deeply interested in bridging ecology, and information and communication technology, as influenced by degrees earned in Agriculture, Computer Science and Environmental Science from UP Los Baños.)