Filipino name for storm surge

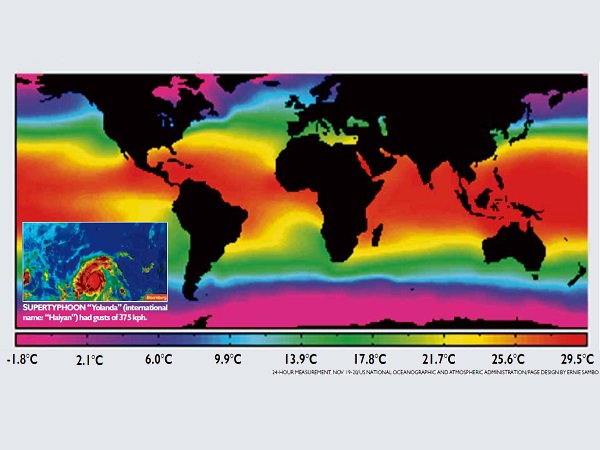

A study conducted by the US National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration shows the Earth’s sea surface temperatures. Notice the dark red portion on the right side of the map? There lies the hottest sea surface temperature. Notice which country lies right in the middle of it? Isn’t that our precious chain of 7,100 islands known as the Philippines? So what does this map mean?

This means that:

Article continues after this advertisement- Warm water is the fuel of typhoons. The hotter the sea surface temperature, the greater the fuel for typhoons. This is the cause of the more frequent and more intense typhoons in the Philippines.

- The warmer the seawater, the greater is the evaporation. The greater the evaporation, the more water vapor collects in the clouds, the process called condensation. Since everything that goes up must come down, this explains the much greater volume of rainfall in the Philippines and in Asia, resulting in more and more flooding.

- The sea east of the Philippines is also experiencing the highest rate of sea level rise. This was verified by a 15-year study by the US National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

This is not rocket science. It is common sense. Clear and simple science tells us that this is the new reality. The Typhoon Yolandas and Pablos, Tropical Storm Ondoys and even habagat (southwest monsoon) that bring heavy rains and flooding are not isolated atmospheric events. They are the new reality and will get worse as the atmosphere of the Earth continues to heat up.

It is like having diabetes. When we are diagnosed with it, the first order of business is to accept it and then commit to reverse it, or live it with the least inconvenience to our well-being.

Unless we understand this and accept this new reality, we will continue to be the victims of these (un)natural calamities. They are not natural calamities. They are all caused by the creature that claims to be the wisest animal on Earth: humans.

Article continues after this advertisementSo what do we do?

Rain gardens

Why is there flooding? Quite simply because excess water has no place to go. Since flooding is the new “state of the world,” we must find a place for the excess water to go. In the natural state, that is the function of lakes, ponds and wetlands. But what did the smart humans do? We filled them up and paved them over with concrete. And then we complain of floods.

To reverse this, we must open up lands, even small portions, to put up rainwater catchment ponds, wetlands and rain gardens.

First, these will only capture and store excess waters that cause flooding. Then, it will restore the water into the underground water table, also known as the aquifer.

As we know by now, land is subsiding because we have been sucking out too much water from the groundwater table without replenishing it. This is exactly what rain gardens can do. It replenishes the groundwater table, the aquifer.

Filipinizing storm surge

Those of us in the field of environmental studies have long known about storm surges, at least in theory. They are tsunami-like waves caused by powerful winds.

However, the reality did not dawn upon me until December 2009. During an amihan (northeast monsoon), the waves of the sea in front of my little house on the coast of Bantayan Island washed up to shore and went all the way up to the road, about 200 meters inland.

Knowing this and seeing the more intense flooding occurring on the island, we decided to rebuild our home with a hundred-meter setback from the shoreline. We call it the Climate Change House. We also dug a man-made mangrove area, and wetland and rainwater catchment pond between the shoreline. More on this later.

Tsu-alon, tsu-balod

When the Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration warned about Yolanda’s “7-meter storm surges,” no one understood what it meant. The people of Tacloban are used to storms and typhoons. But they had no idea they faced tsunami-like waves.

We should coin a word for storm surges. For lack of a better word at the moment, the Tagalogs can call it tsu-alon. For us Bisayans, we can call it tsu-balod. It can mean “a wave (alon or balod) that is like a tsunami.”

Call it by whatever term, but what is important is that it has a name understood by our minds and hearts. Only then can we prepare for it.

Secure water, food sources

Our total dependence on piped running water makes us most vulnerable to electrical shutdowns caused by floods or typhoons. We must go back to basics. The old-fashioned atabay (in Bisaya) or balon (in Tagalog) must be a mainstay in all communities.

In the event of ever-frequent emergencies, they will be a most valuable source of life—water.

THE CLIMATE CHANGE HOUSE was the only structure relatively intact in the School of th SEA in Bantayan Island, Cebu province, after Supertyphoon “Yolanda” struck on Nov. 8. The structure is on stilts as a measure against storm surges. CONTRIBUTED PHOTO

Rice vs root crops, vegetables

One of the greatest myths of human civilization is the myth of rice. It is not only nutritionally useless, it is also very harmful to health. Nutritionists tell us that one cup of rice has the sugar content (aka the glycemic index) equivalent to eight spoons of sugar. That is why people who have diabetes are not supposed to eat rice.

The ecological costs of cultivating rice are extremely high. Wetlands, which are supposed to absorb excess waters, are converted into rice paddies that emit methane—a gas that is one of the causes of the global heating.

In addition, there is the intensive need for water to irrigate paddies, the constant poisonous chemical inputs from fertilizers and pesticides, and the backbreaking labor needed to grow and process rice.

Rice is also very vulnerable to the uncertainties of the weather. If it is too hot, it dries up. If it is too wet, it is soaked and dies. If it is hit by strong winds, the grains are blown away. And in the event of an emergency, rice is very difficult to transport and cook.

Look at our brothers and sisters in the Batanes Islands up north. They are so used to powerful typhoons that they plant root crops for their staple. Camote (sweet potato) is one of the most nutritious and highly resilient root crops. Its leaves and its roots are edible, even raw if necessary. As the Spanish say, “en tiempo hambre, no hay mal pan.” In times of hunger, there is no bad food (bread).

Resilient houses

We like the picture of the bahay kubo—the quaint thatched-roof structures made of bamboo or sawali (woven bamboo mat) and other light materials.

However, that age is gone, forever, especially in coastal areas. Between the more intense typhoons and storm surges, flimsily built houses is one sure way of getting ourselves killed.

We need to reengineer our cities and human settlements far away from the coast. Also, let us understand that single-detached housing, especially for the poor, is neither safe nor cost-effective. It is time to build multifloor, medium-rise, collective and climate-resilient housing.

The biggest cost of a building is the land. The government can buy this.

National design contest

To design climate-resilient dwellings, we can launch a nationwide competition among architecture students and architects. These designs can then be adapted according to the local climate of a region or province.

After Typhoon “Frank” hit us in Bantayan Island in June 2008 and destroyed the original structure of the School of the SEA (Sea and Earth Advocates), we learned our lesson. We rose to build the Climate Change House.

First, we relocated it about 100 meters away from the beach line. Between the beach and the house we put up a man-made brackish-water lagoon (and evolving mangrove forest) as a buffer in the event of a storm surge. The house is also on 10-foot concrete stilts as a measure against the floods and tsu-balod.

The ground floor is kept open. During ordinary times, it can be used for various purposes. But in case of a weather emergency, it is easy to abandon and go up to the second floor or to the roof-deck.

Around the windows are plant boxes with vegetables and camote as ready sources of food in an emergency.

Concrete roof

Instead of galvanized iron (GI) sheets for a roof, we built a concrete roof. It now serves as the roof-deck edible garden. To ensure constant water supply, there is an old-fashioned well at the bottom that is protected against flooding. We manually pump the water to a tank up on the roof-deck using a hand pump. That tank then supplies the water needs of the Climate Change House.

Did it work?

Yolanda hit us very hard in Bantayan Island on Nov. 8 and flattened entire villages. Out of the eight structures in the School of the SEA, only two remained standing. Out of the two, only the Climate Change House was relatively unscathed. The camote plants remained intact and ready to eat.

People used to laugh at me because I built a structure with seemingly weird features fitting of a “Doomsday Prepper.” But a lawyer is trained to think logically and draw conclusions only when supported by evidence. The clear scientific evidence—the writing is on the wall—have been there for a long time and for all to see.

Now that the climate crisis has become a reality, maybe people will begin to listen. The opportunity for us to shine is staring at us right in the face. We can use the community spirit of bayanihan to build these low-rise collective (condominium) residences using the model popularized by the Gawad Kalinga and the Habitat for Humanity movement.

Model condo complex for poor

Those who can afford give the materials, government buys the land and the people put in their sweat equity.

One such model of collective poor man’s condominium complex already exists in the Baywalk of Puerto Princesa City in Palawan, built by former Mayor Ed Hagedorn.

Unlike ordinary tenement housing, the design and structure of these “condos” rival some of the high-end condos. And how much do the people pay per month? Only P800, (or about U$19), barely the equivalent of a meal for two in a small restaurant.

Emergency vehicles

Do we need fighter planes that will cost hundreds of millions of dollars? Do we need more helicopter gunships? What for? To fight China? Let us not joke ourselves.

Or do we need more transport helicopters and planes, more amphibian vehicles, and more transport and hospital boats?

It was sad to hear certain individuals blaming others instead of coming to the rescue of the people of Tacloban. Have we ever experienced being in the center of a 300-plus kilometer-per-hour typhoon in a city that was entirely swamped by a tsu-balod?

Sadder even was the report that a national official was in some power tiff with the mayor. The squabble so escalated that it had to be refereed by the President.

Some have asked: If the mayor were a member of the party in power, would he receive the same treatment? As my son Uli says, “Kung hindi ka dilaw, ang may sala ay ikaw” [If you are not yellow (the political color of the party in power), you are at fault].

If there is any place that knows of typhoons, it is Tacloban and Eastern Visayas and the Bicol region. They have typhoons for breakfast, lunch and dinner.

Not commonly understood

But then it was not the typhoon that killed the people and caused so much destruction on Nov. 8. It was the tsu-balod (the storm surge). In the first place, our people did not understand what a storm surge was because it is an English term that does not have a commonly understood local translation. This was compounded by the fact that our people have never experienced a storm surge of such magnitude.

Thus, the warnings of a 7-meter storm surge did not seem real to us. Had our weather bureau better explained what a storm surge was or called it a tsunami-like wave, the people of Tacloban would have run for their lives and rushed to higher ground.

Besides, how many times have we experienced the power of a typhoon Signal No. 4? Come to think of it, yes, we experience it every day. But it does not come in the form of wind and rain. Rather, it comes in the form of political egos with sustained winds of a typhoon Signal No. 10.

Talk about preparedness. Is the pot calling the kettle black? How many cargo helicopters do we have? None? How many C-130 cargo planes do we have? Three? How many satellite phones did the National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council have? None.

Let us thank our lucky stars, and the international community, for coming to our rescue.

We will rise again

There are two things that we need to do:

- Accept the climate crisis as the new normal.

- Unleash the genius of Filipino resilience.

- Unless we embrace the first, we will continue to be the victims of this never-ending tragedy, year in and year out.

But if we understand and embrace this new reality, we can then unleash the native genius of Filipinos and emerge as victors. We can even show the world how we can turn climate adversity into a climate of opportunity.

We, the people, must ask ourselves: In the face of this climate crisis, will we be the victims? Or will we be the victors?

The choice is ours. If we choose right, we will rise again, stronger and better than ever.

(Tony Oposa Jr. is an environmental law advocate.)