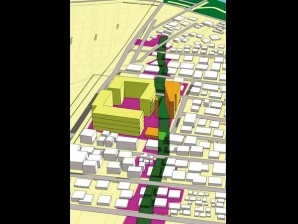

A 3.4-KILOMETER linear park, with a 10-meter easement from the fault line, will have trees and plants. The illustration includes a school built on the fault line. PHOTO FROM NEW MAKATI CLUP

In most parts of Barangay Sta. Cruz in Makati City, residents have been accustomed to pockets of flooding during heavy rains.

“Whenever it rains really hard, the floodwater rises up to the gutter,” said Elisa Lopez, a 60-year-old resident of Montojo Street. Lopez noted that Barangay Sta. Cruz had sprawling rice fields half a century ago.

During typhoons or monsoon rains, which normally last for days, dark grey water from the nearby Manila South Cemetery gets into her rundown house.

When Typhoon “Maring” dumped a month’s worth of rain on parts of Metro Manila on Aug. 20, the water inside her house was knee-high. She and her family had to move their furniture and appliances to higher ground.

Flooding getting worse

“I have been here for 60 years and it only gets worse every year,” she said.

On that day, even the exclusive Magallanes Village was not spared by the severe floods, which reached as high as a one-story house in parts of the subdivision.

Water from Maricaban Creek flooded the Magallanes Village house of the man in charge of the country’s antiflood projects, Public Works Secretary Rogelio Singson.

Street flooding has become a common sight that residents have stopped complaining, said Carlito Marquez, 33. “But it remains a burden on residents, especially those who go to work in their office clothes. You don’t expect them to just wade in the floodwater. And of course, there’s the danger of contracting leptospirosis,” he said.

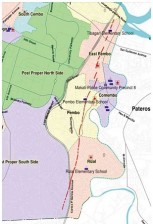

THE WEST Marikina Valley Fault (red broken lines), which runs from Marikina to Batangas, cuts across Barangays East Rembo, Comembo, Pembo and Rizal in Makati. PHOTO FROM NEW MAKATI CLUP

Makati, though one of the richest cities in the country, is as vulnerable as other cities in Metro Manila, said Merlina Panganiban, head of the Urban Development Department (UDD) of Makati City.

VP home inundated

She said that even the house of Vice President Jejomar Binay—the longtime mayor of Makati before his son Junjun took over—on Caong Street in Barangay San Antonio, was often inundated.

Makati is a catch basin while a segment of the 67-kilometer West Valley Marikina Fault, cuts across the eastern part of the city.

The recent calamities pushed the local government unit to consider disaster risk reduction in planning developments in the city for the next 10 years.

Mainstream risk reduction

The 10-year Comprehensive Land Use Plan (CLUP) of Makati for 2013-2023, which took effect on Aug. 8, promises a lot of things, including a multipurpose sunken garden in Barangay Tejeros that will serve as a water retention pond, a linear park along the West Valley fault and other open spaces.

Approved by the Housing and Land Use Regulatory Board after it underwent public scrutiny in 2012 through consultations, the CLUP works as a guide for Makati officials on what to do in the next decade.

The fact that Makati is the first city to “mainstream risk reduction” is like a double-edged sword.

Setting benchmark

Panganiban said that while the city takes pride in setting the benchmark for other local government units crafting their own CLUPs, being the first to set up a disaster-sensitive CLUP was difficult.

“Even until now, there is no harmonized guidelines or standards for mainstreaming disaster risk reduction in the CLUP available for the local government units (LGUs),” Panganiban said.

THE SUNKEN open space can have an amphitheater and a skateboard park. It is proposed to be built in Barangay Tejeros. PHOTO FROM NEW MAKATI CLUP

He said the urban planners at first didn’t know what processes to follow and what components of disaster management to consider.

But with the help of local and international experts, the UDD managed to produce one, which according to Makati Mayor Junjun Binay was one of its kind and would serve as a model for other LGUs in the country and even across Asia.

Redoing developments

Panganiban said that it was impossible to bring the environment back to its original state. “But yes, we can rectify our development efforts in the past and make it better in the future.”

She said it was fairly known that fault lines and river easements were danger zones, but because of the lack of accurate and reliable data, and political will of Metro Manila’s previous leaders, human settlements in these areas were allowed to multiply like mushrooms.

In the case of Makati, the CLUP declared that the river easements and the fault zone, which are already occupied, should be converted into open spaces.

“Strictly, we are not allowing any further developments in these areas and eventually we will relocate families living there to safe places within or outside Makati,” Panganiban said.

From fault to park

The Makati’s UDD personnel have begun surveying the four barangays straddling the West Valley Fault.

Panganiban said at least 300 structures, including Pembo Elementary School on Escarlata Street, stand on the most dangerous spots in Makati, particularly when a big earthquake strikes. (See related story.)

“All structures along the 10-meter easement of the fault line (five meters from both sides) should be cleared,” she said.

Panganiban said she did not use the word “demolition” since most of the residents knew the danger they were in and were convinced of the need to move to a safe place.

BY ALLOCATING an area for a sunken open space, it can also serve as a detention pond in cases of extreme rainfall events. PHOTO FROM NEW MAKATI CLUP

“It’s either we provide them compensation or we offer them housing units in resettlement areas,” she said.

Earthquake study

The CLUP also made mention of scenarios in case the fault line starts to move according to a joint study that the Japan International Cooperation Agency, Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology (Phivolcs), and Metropolitan Manila Development Authority conducted from August 2002 to March 2004.

Titled the Metro Manila Earthquake Impact Reduction Study, it identified 18 possible earthquake scenarios that may heavily affect the metropolis.

Worst-case scenario

Model 13 is a huge subduction type (a tectonic plate moving under another tectonic plate) magnitude 7.9 earthquake along the Manila Trench that generates a tsunami. Model 18 is a magnitude 6.5 strike-slip earthquake reminiscent of the 1863 earthquake in Manila Bay. Model 8 is a magnitude 7.2 strike-slip type earthquake along the segment of the West Marikina Valley Fault.

According to the UDD, among the 18 scenarios, Model 8 is the worst as it is expected to produce more intense ground shaking.

Since 2007 when the city’s zoning ordinance was amended, no additional structures and improvements in existing ones were allowed along the fault.

Panganiban said once the structures, both private and public, were completely gone, the 3.4-km segment from Barangay West Rembo up to Rizal, would be turned into a linear park filled with trees and plants.

“Biking and jogging might be allowed in the area but we want to keep it bare since it is a fault zone,” she said.

“If a resident’s property happens to fall on the easement, the entire property should be cleared,” the UDD chief said.

Makati, however, still needs to verify the accuracy of the fault zone map of the Phivolcs through more diggings “just to make sure,” Panganiban said.

Evacuation center

The CLUP also requires each barangay and private subdivision in Makati to designate an open space as an evacuation center in case an earthquake occurs.

“Parks and open spaces have the potential to serve secondary roles as evacuation centers of staging areas for emergency response and relief during disasters,” Panganiban said.

Building owners and companies in commercial zones within 200 meters from a rail station will be given “a bonus incentive of additional floor” for the development of a network of green and open spaces or iconic spaces and landmarks that would give the city a positive and distinct image.

Amphitheater vs floods

The western portion of Makati, which includes Barangays Sta. Cruz, Tejeros, Singkamas and Kasilawan, is among those considered flood-prone areas and would be “redeveloped” in the next 10 years.

One of the projects in Disaster Resiliency Initiatives for Vulnerable Enclaves (DRIVE) is a sunken open space that can temporarily impound the runoff water to avoid the flooding of streets and homes during a heavy downpour.

On a sunny weather, the open space proposed to be located in Barangay Tejeros could be a community facility for sports and recreations like skateboarding.

It can also be an amphitheater, outdoor performance venue, or a children’s playground.

The park or the water retention pond remains a concept until the UDD crafts a master plan by this year or the following year.

Partnership

The master plan would also include the money aspect and tackle whether the city government would shoulder the cost or pass it on to the private sector by way of a public-private partnership agreement.

Also under DRIVE is the redevelopment of Bliss housing projects, such as the one in Barangay Tejeros.

In all areas classified as medium-density residential district, the CLUP increased the height limit of structures from 14 meters to 18 meters as long as the ground floor would be designated as an open area.

The added height is meant not only to reduce traffic congestion but also to mitigate the effects of rising levels of flooding. The increase in building height, considered a climate-change adaptation, was reflected in Zoning Ordinance No. 2012-02 that adopted the new CLUP.

Tax break for rain catcher

Other flood-mitigation measures adopted in the new CLUP are:

Require taller buildings to install individual rainwater harvesting systems that store rainwater onsite rather than discharging it into the storm drainage systems. Collected water can be used for landscaping and cleaning of grounds and paved areas.

Offer tax breaks and other incentives to encourage building and property owners to invest in rainwater-harvesting systems.

“We cannot totally stop floods from happening since we can’t change the fact that we are one of the catch basins of Metro Manila. But we can do something to make them recede faster,” Panganiban said.

Another measure is to remove informal settlers from choked creeks and waterways. “We have been slowly bringing these spaces back to the rivers and waterways, and moving families to relocation sites,” Panganiban said.

Records of the UDD showed that there were 4,975 informal settler families in Makati as of 2012 that needed housing elsewhere.

Priority

The UDD has received orders from Mayor Binay to prioritize the disaster-risk-reduction projects and to at least get projects under DRIVE like the water retention pond and linear park started, if not completed, by the end of 2016.

To fund its disaster-risk-reduction projects, the city has been setting aside 5 percent of its regular income each year since 2011 as mandated by Republic Act No. 10121 or the Philippine Disaster Risk Reduction Management Act of 2010.

All in all, it has allotted an average of P1.3 billion yearly from 2011 until 2013 to disaster-risk-management projects.

Panganiban said spending a portion of the city’s budget to establish infrastructure for disaster resiliency would be worthy long-term investments.

“The ultimate goal of making disaster risk reduction our top priority in crafting the CLUP is that after 10 years Makati would be a resilient city,” she said.