Why is the Philippine economy not producing enough good jobs despite higher gross domestic product (GDP) growth rates in the last decade? Is there a silver bullet that can solve the jobs challenge?

Policymakers and even ordinary citizens ask these questions. The same questions guided our search for answers in the last two years as we prepared the Philippine Development Report (PDR) “Creating More and Better Jobs” aimed at untangling this glaring development paradox.

What we found is that there are no easy solutions as the challenge is linked to deep-seated structural issues in the economy. Only a comprehensive reform program, supported by a broad reform coalition, could get the country on an irreversible path to inclusive growth.

Challenge

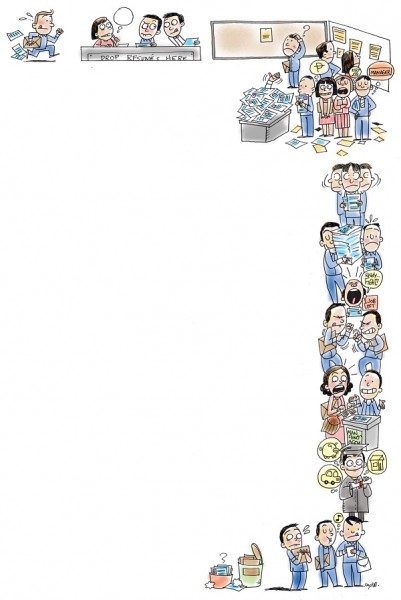

The Philippines faces an enormous jobs challenge. By jobs we mean what people do to make a living. It includes formal work and informal work. It covers wage workers and self-employment. Good jobs are those that raise real wages and bring people out of poverty.

Good jobs need to be provided to three million unemployed Filipinos and seven million underemployed Filipinos in 2012, and to around 1.15 million entrants to the labor force every year. That is a total of around 14.6 million jobs that need to be created in the next four years.

Every year in the last decade, only about a fourth of the entrants to the labor force get good jobs. Of half a million college graduates every year, 240,000 can be absorbed in the formal sector, such as business process outsourcing (BPO). About 200,000 find jobs abroad and around 60,000 will be unemployed or exit the labor force.

Low skill, low pay

The remaining 650,000 entrants, around half of whom have high school degrees, often have no other option but to find or create work in the low-skill and low-pay informal sector.

Under the current high-growth scenario and the removal of key binding constraints in fast-growing sectors, the formal sector will be able to provide good jobs to around 2.2 million people in the next four years, or around double the current figure.

But the majority of Filipino workers would still be left out. By 2016, around 12.4 million Filipinos would still be unemployed, underemployed or would have to work in the informal sector, where moving up the job ladder is difficult for most people.

Underlying causes

With growth accelerating to historic highs, why is the economy still having difficulty in creating more and better jobs? This is because the country’s long history of policy distortions has slowed the growth of agriculture and manufacturing in the past seven decades.

Instead of rising agricultural productivity paving the way for the development of a vibrant labor-intensive manufacturing sector and subsequently of a high-skill services sector, the converse has taken place in the Philippines. Agricultural productivity has remained depressed, manufacturing has failed to grow sustainably, and a low-productivity and low-skill services sector has emerged as the dominant sector of the economy. In other words, the Philippines failed to undergo a structural transformation.

Underlying this is the lack of competition in key sectors, insecurity of property rights, complex regulations and severe underinvestment that have led to this growth pattern, which is not the norm in the East Asia region.

This anomalous growth pattern has failed to provide good jobs to a majority of Filipinos. As a result of weak employment generation, poverty and inequality are slow to improve, informality is prevalent and outmigration has become the norm for millions of qualified workers.

Window of opportunity

Today, a window of opportunity exists to accelerate reforms that will create more and better jobs. The country is benefiting from strong macroeconomic fundamentals, political stability and a popular administration that many see as committed to improving the lives of the people.

It also stands to benefit from the global and regional economic rebalancing and the strong growth prospects of a dynamic East Asia region.

Moreover, the country also has a history of successful reforms that created many new jobs and raised incomes. During the Ramos administration, several industries, notably the telecoms and airlines industries, were opened to competition. Economic growth and job creation that followed the liberalization demonstrated the economic potential that the monopolies had long suppressed.

BPO jobs, air travel

Without these key reforms, sustained growth in the last decade and strong job creation in some industries would have been difficult to achieve. The benefits of these key reforms are unmistakable:

Five million new jobs were created, including 800,000 jobs in the BPO industry. The BPO success has also led to the development of the countryside through the next wave cities.

In 2010, there were over 80 million mobile phone subscribers and over 20 million Internet users.

Access to the Internet has helped build stronger demand for good governance and has helped improve disaster risk management, as citizens share information about flooding.

Travel cost has gone down by 50 percent. Twenty million Filipinos are now flying from less than 5 million two decades ago, with strong impact on tourism.

No easy path

What we found in our two-year research and consultations for the PDR was that there was no silver bullet to address the jobs challenge. To create more and better jobs, the country will need to urgently accelerate comprehensive reforms across a range of sectors to create a business environment conducive to private sector job creation, particularly by small and medium enterprises.

Several reforms have successfully started, notably in public financial management, tax policy and administration, anticorruption and social service delivery. The government now needs to maximize the chances that the country will follow a more inclusive growth path and meet the jobs challenge by accelerating reforms to protect property rights, promote more competition and simplify regulations, while sustainably ramping up public investments in infrastructure, education and health.

The PDR provides a detailed discussion of these recommendations as our contribution to the policy debate. What is needed now is to address the issue of how to reform. We believe that addressing this issue begins with key stakeholders agreeing to work together.

Coalition for reform

Many stakeholders agree that the current window of opportunity marks a critical juncture in the country’s history. To put the country on an irreversible path to inclusive growth, a broad reform coalition—that is, a multisectoral group composed of many interests that can address diverse options—is crucial.

A broad reform coalition is needed for two reasons:

First, it increases the likelihood that reforms are sustained since the presence of a broad coalition makes it difficult for one subgroup (e.g., vested interests) to block the reforms. Without a broad coalition, reforms made under a strong president can be reversed.

Second, because it must adopt a strategy that appeals to a wide segment of society, a package of reforms that balances trade-offs and proportionally assigns responsibilities can be formulated instead of tackling reforms one by one, which can generate powerful opposition from vested interests and quickly drain the energy and capital for reform.

In the absence of a crisis to rally stakeholders around a common goal, the success of the Aquino administration in generating confidence and economic growth, and the obvious advantages for everyone to see such growth continue beyond this administration, suggest that a basis for a broad-based coalition is present. Strategically forging this reform coalition should be a high priority of the government and its partners.

This broad coalition can begin with the tripartite members. Its membership can be expanded to include marginalized stakeholders. The PDR recommends that government, business, and labor (including informal workers), supported by civil society, engage in deeper social dialogue and partnership, and agree on an agenda on job creation for all Filipinos.

Balanced reform package

A win-win agreement to create more and better jobs requires a careful balancing of trade-offs, proportional sharing of responsibilities based on ability to shoulder the reform cost, short-term sacrifices on all sides, and mutual cooperation and trust that transcends the usual issues of rights, labor standards and wages in order to address issues of productivity and competitiveness so that more people can benefit.

An example of a package of reform could be one that increases real income and create more opportunities to move up the job ladder. The reform package could look this way:

Government could prioritize programs and reform measures to help reduce food prices (e.g., further liberalized food imports and reform of the National Food Authority). At the same time, government could ramp up investments in rural infrastructure and support services so that food prices can fall without farm profits falling.

It could commit to providing universal social and health insurance at higher quality, and cofinance training and apprenticeship programs, say, for disadvantaged groups and young workers. Finally, it could simplify the tax code and business regulations to promote competition and encourage the growth of entrepreneurship.

Businesses could support reforms that promote competition to level the playing field, such as making all tax holidays and other fiscal incentives temporary. Businesses also need to fully support freedom of association and collective bargaining, commit to offering more training opportunities for workers, and improve the link between wages and productivity.

Labor could agree to recognize valid forms of flexible contracts and reduce calls to hike minimum wages as food prices fall.

Civil society could intensify efforts to ensure broad-based participation and support for this agreement.

Sequencing

In sequencing the reform program, a three-track approach can be considered by the government and the reform coalition to produce early results and build momentum for the more difficult reforms.

Reforms in the first track are those that are supported by a reasonably broad set of stakeholders and generally do not need legislation. These include:

In agriculture, fully transferring importation of rice to the private sector by abolishing import licenses.

Relaxing cabotage rule (or allowing foreign ships to ply domestic shipping routes) to reduce interisland shipping costs and food prices. In addition, we suggest reducing the Foreign Investment Negative List to attract more foreign direct investments into the economy.

With respect to social protection, regularly updating the National Household Targeting System for Poverty Reduction, which is currently used for the conditional cash transfer program and using it to systematically target all social protection programs (e.g., rural poor, universal healthcare and disaster-related support).

The second reform track is about accelerating current reforms and giving them more focus. These include the following:

In agriculture, accelerating the systematic and administrative adjudication of property rights in rural and urban land to reduce insecurity in land, including land redistributed under the agrarian reform programs. There is also the need to increase spending on agricultural infrastructure (e.g., farm-to-market roads, irrigation).

In manufacturing, fast-tracking the implementation of the power retail market to bring down power costs.

To simplify business regulations, ensuring full implementation at the local government level of the online business registration and licensing system.

To enhance transparency, enhancing open government and open data initiatives.

The third track is to lay the foundation for the more difficult reforms. They will take time to be completed and may even surpass the horizon of the current administration. Many will need legislation. However, decisive action beginning with a policy pronouncement can be taken today to start the process. These include the following:

In agriculture, replacing the existing rice import quota with a tariff, which can then be gradually reduced over the medium term, so that food prices go down.

Formulating an overarching competition policy to promote more competition and protect consumer rights.

In addition, reviewing and simplifying the many and complicated business regulations, especially for microenterprises and small businesses.

Finally, defining valid forms of flexible labor contracts to provide more job opportunities to millions of informally employed workers.

Structural transformation

Successful implementation of agreements such as the one outlined above could help the country restart its structural transformation by reviving agriculture, supporting manufacturing and creating better jobs in the services sector.

This would allow the country to move from the current pattern of high growth but high poverty and weak employment to a pattern of higher, sustained, and more inclusive growth, with more and better job creation, and faster poverty reduction.

(Karl Kendrick T. Chua is the senior country economist of the World Bank for the Philippines. He is the main author of the flagship report of the World Bank Philippine Office: the Philippine Development Report “Creating More and Better Jobs.” He completed his MA in economics in 2003 and Ph.D. in economics in 2011 at the University of the Philippines School of Economics.)