The rapidly unfolding reconfiguration of societies in the world today has generated new and more nuanced ideas about international relations, state-citizen interactions, national identity and state sovereignty.

For one, states are becoming less able to assert their sovereignty in the face of the expansionary policies of global hegemonic players. But globalization’s other face has also been unmasked as shown by the 2013 crisis in the once-stable European Community and the world-wide impact of the US economic meltdown of 2008-2009.

Vulnerable developing states are forced to seek help from international financial institutions and foreign governments in return for instituting painful reforms that compromise further their national autonomies.

But economic crises also breed political crises, resulting in instances of drastic regime changes.

Deepening inequality

Despite the hegemony of global capitalism and its vaunted superiority in production and wealth creation, social and economic inequality continues to deepen in both developed and developing societies. This has created wide swaths of social unrest as exemplified by the Occupy Movement in the United States that spread to other parts of the world.

In Latin America, left-leaning governments have emerged as a powerful challenge to the dominant capitalist meta-narrative.

Poverty, joblessness and deteriorating productive sectors in many developing societies have unleashed a global trend of overseas contract work and permanent migration to more developed societies.

This has created pockets of communities with dual or multi-identities, thus blurring further the notion of a single national identity.

These state and market failures have focused attention on society’s third sector—civil society. Social movements, popular organizations, advocacy groups, progressive intelligentsia and community-based organizations have staked claims in their respective societies’ political spaces. It is within these forces that alternatives to the existing systems can be sourced and realized.

Territorial disputes

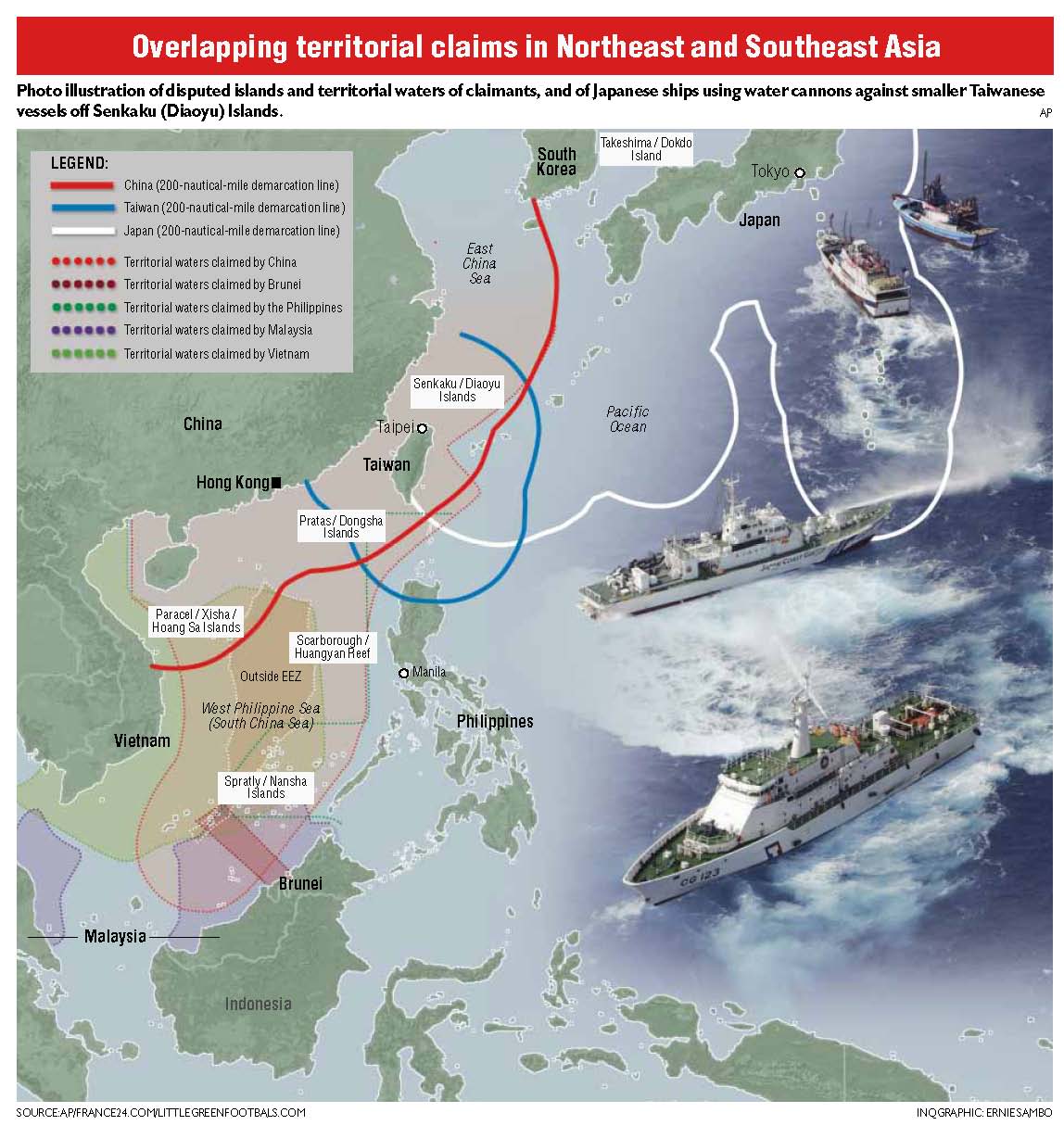

These economic and political developments bear down on and are relevant in the issue of territorial disputes in Northeast and Southeast Asia. Disputed territories and their respective protagonists include:

The Diaoyu (Senkaku) Islands – China, Taiwan and Japan;

Dokdo (Takeshima) Island – Korea and Japan;

The Spratly Islands and other territories in the South China Sea (West Philippine Sea) – China, Taiwan, Vietnam, Brunei, Malaysia and the Philippines; and

The Kuril Islands – Japan and Russia.

Conventional discussions and debates on territorial disputes have focused on the issues of nationalism, national identity, sovereignty, territorial integrity and state boundaries.

In many cases, manifestations of chauvinism, jingoism and right-wing ultrapatriotism have surfaced. Such an atmosphere makes almost impossible the peaceful resolution of territorial conflicts.

There is a need to move away from divisive issues and surface instead alternative approaches that would foster unity and cooperation among the parties.

Furthermore, the interests of local communities, which are directly affected by these conflicts, must be upheld. The conceptual ideas behind these alternative approaches can be gleaned from various papers, books, statements, conference proceedings and research proposals that expound on this problem.

Shared identity

Kinhide Mushakoji, in his paper “Identity Politics in the Developmentalist States of East Asia,” argues that the present age has given rise to “multi-identity, multiethnic and multicultural societies” brought about by the “massive influx of foreign migrants forming diaspora communities” in host countries.

This has necessitated the “development of multilevel hierarchy of identities among overlapping identity communities.”

Mushakoji rejects the narrow view that national identity is the only legitimate identity and foresees the creation of a regional identity shared by citizens of various neighboring countries where divergent national identities are recognized and respected.

While he does not specifically refer to territorial disputes, the implications on the issue are evident. Too often have notions of a national identity and territorial integrity based on an imagined homogenous racial stereotype been used to escalate intersocietal conflicts. A shared regional identity will go a long way in easing tensions among nations and facilitate the peaceful resolution of disputes.

Commons principle

Nobel Prize laureate Elinor Ostrom, in her book, “Governing the Commons,” asserts that the age-old system of a common pool resource (CPR) has been a viable formula for getting people of various backgrounds and classes to work together for the common good. CPR is defined as “a natural or man-made resource system that is sufficiently large as to make it costly to exclude potential beneficiaries from obtaining benefits from its use.”

Using the theory of collective action, Ostrom examines how “individuals might be able to achieve an effective form of governing and managing their own commons, (and) commit themselves to a cooperative strategy … to share equally the sustainable yields” from the resources under their control.

Although Ostrom limited her discussion to communities of individuals or families, the parallelism with territorial disputes is how what would otherwise be irreconcilable interests in exploiting and benefiting from natural resources could be set aside for the good of all contending parties.

For Prue Taylor, the concept of the common heritage of mankind “establishes that some localities belong to all humanity and that their resources are available for everyone’s use and benefit, taking into account future generations and the needs of developing countries.”

Unclos

At the United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea (Unclos III), developing countries stood together against the developed states led by the United States and asserted the doctrine that the international seabed and their resources are the “common heritage of mankind” and therefore “belong to everyone and (are) to be exploited by all.”

This was in opposition to the free-market-oriented view of “freedom of the seas,” i.e., “that they belonged to no one and can be exploited by anyone,” a view espoused by technology-rich states. Teresa Encarnacion says that the eventual adoption by Unclos III of the developing countries’ position was “of great significance … because importance is placed on the need to cooperate and work closely together and not to compete to develop the resources of the international seabed area.”

Professor Thanh-Dam Truong addresses the territorial disputes issue in East Asia in a proposed research on “Asean-China Relations and the South China Sea (SCS).” Rather than relying on a purely legalist perspective, she uses a constructivist approach to transforming the view on SCS as China’s regional sphere of influence into an Asean-China regional common.”

Code of conduct

Truong’s framework includes the formulation of a China-Asean code of conduct for maritime cooperation, focuses on sustainable development initiatives, stresses regional norms as part of international frameworks using norms shaping and sharing (rather than diffusing) and adopts the language of human security as a “people-centric concept expressed locally.”

Thus, the “security of livelihood” of small-scale fishers is to be prioritized as they are “caught between China’s patrol of (its claimed) U-shaped line and large fishing operations that suck up resources due to superior technology.”

Rasti Delizo departs from an exclusively state-centric standpoint in proposing that the SCS area already be declared a “Shared Regional Area of Essential Commons” that has to be “recognized and upheld by all the common stakeholders presently involved in the region’s long-term future,” including “state and nonstate entities, together with various regional organizations and even global institutions.”

Joint development

He stresses the principle of collective sharing of “all the commonly essential natural maritime resources that are now presently found (and yet to be discovered)” within the South China Sea.

In September 2012, some 1,900 Japanese civil society personalities issued “A Citizens’ Appeal to Stop the Vicious Cycle of Territorial Disputes.” The group takes note of the conflict’s historical background—that of Japan’s aggression against its neighbors, decries the fanning of nationalist sentiments around the conflicts, and questions the notion of a “fixed inherent territory.”

The statement proposes the “joint development and use of the resources in the areas … now under dispute (as) the only way forward.” While recognizing that “sovereignty cannot be divided,” it asserts that it is “possible to jointly develop, manage and distribute resources in the area.”

The Japanese group appeals to the countries involved to establish “a foundation for regional cooperation” by “pursuing dialogue and consultation to come to an understanding over resources and share interests “rather than clashing over sovereignty” and flaring up “territorial nationalism.”

Popular voices

The group statement also notes the historical fact that the marine areas around Senkaku have “been a place of fishing, exchange and life for Taiwanese and Okinawan people, an ocean of production” and that, therefore, their voices must be respected. This view brings the debate outside the realm of state and sovereignty interests to the more people-centric community level.

The Mingian East Asia Forum on “Facing History, Resolving Disputes, and Working Towards Peace in East Asia” held in October 2012 in Taiwan traces the current conflicts to the “yet-to-be-resolved problem of colonial and imperial history since the late 19th century” and the consequent “Cold War structure.”

The term “mingian … refers to the nongovernment, popular voices and organizations initiated by the people.”

The Forum statement recommends that the disputed islands be transformed into spheres of border interaction (where people can freely interact), subsistence spheres for neighboring communities (where people share the resources) and demilitarized zones.

The Forum rejects “nationalist modes of thought on territorial sovereignty” as having a negative impact on “earnest attempts to seek people-to-people solidarity, exchange and dialogue, mutual cooperation and peace.”

As with other alternative viewpoints, the Forum asserts that “the insistence on sovereignty alone will not resolve the controversy.”

Respective governments are called upon “to refrain from intensifying nationalist sentiments within its borders and to avoid any acts of violence and aggression against people.”

East Asian countries and mingian societies must espouse “the principles of people-to-people solidarity, communication and dialogue, and mutual help and collaboration.”

Rights of fisherfolk

In the midst of the tense disputes over territorial waters being waged by governments, the plight of small-scale fisherfolk may grow to be a major issue, especially in the South China Sea as some observers see the conflicts in the area as all about one thing: fish.

Stephanie Kleine-Ahlbrandt notes that “despite the overwhelming preoccupation with the potentially abundant energy reserves in the South China Sea, fishing has emerged as a larger potential driver of conflict” with the Philippines, Vietnam and China relying “on the sea as an economic lifeline.”

One must, therefore, be cognizant of the rights of small-scale fisherfolk lest they be further marginalized and disempowered by the operations of large fishing companies and the unfriendly policies of governments.

The UN Food and Agricultural Organization, in its Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries, recognizes the concerns of small-scale and artisanal fisheries as a fundamental human right and enjoins states to “appropriately protect the rights of fishers, fishworkers, and small-scale fisheries to a secure and just livelihood, as well as preferential access to traditional fishing grounds and resources.”

Multilateralism

Alternative approaches to resolving the territorial disputes in Northeast and Southeast Asia hinge on a commitment to the principles of collective action, multilateralism, a shared regional identity, and people-to-people concerns.

On the other hand, the uncompromising assertion of absolute sovereignty, permanent territorial rights and bellicose nationalism could only be counterproductive and lead to escalation of the conflicts.

In a world of greater interaction between governments and societies, the porousness of national borders, rapidly dwindling resources, and looming and actual environmental disasters, it is imperative that states and market forces act more responsibly and take a less belligerent and more reasonable attitude to existing territorial disputes.

On the part of civil society and nonstate players, their human resources and talents must be equally harnessed to achieving the goal of a socially just, economically equitable and less conflictual planet.

(Eduardo C. Tadem, Ph.D., is professor of Asian Studies at the University of the Philippines Diliman and editor in chief of Asian Studies journal. This article is a condensed version of a paper presented at the fifth International NGO Conference on History and Peace, Kyung Hee University, Seoul, South Korea on July 22-24.)