When the United States lost its way

In 1981, the diplomatic historian Robert C. Hilderbrand wrote a pioneering study of the first attempts by the US government to “manage” public opinion. The book’s early chapters focus the spotlight on William McKinley, the president who prosecuted the Spanish-American War and launched the American conquest of the Philippines.

In 1981, the diplomatic historian Robert C. Hilderbrand wrote a pioneering study of the first attempts by the US government to “manage” public opinion. The book’s early chapters focus the spotlight on William McKinley, the president who prosecuted the Spanish-American War and launched the American conquest of the Philippines.

I found the following paragraph in the first chapter (titled “In the Ways of McKinley,” an allusion to one of the standard accounts of the McKinley years, Margaret Leech’s “In the Days of McKinley”) all but revelatory.

“In March 1897, the president’s staff comprised only six typists and clerks, one of whom was detailed to handle the first lady’s correspondence; by the end of the year, his entourage had grown to eighteen. Even this proved insufficient, however, when the responsibilities of war and empire added to administrative duties, so that by 1901 the White House staff grew to more than eighty assistants. One reason for this expansion was the added clerical work of preparing and distributing press releases; one result was more time for dealing with Washington correspondents.”

The point is worth belaboring: When McKinley took office in 1897, the White House office staff consisted of only six typists and clerks. By the time of his assassination four years later, the staff had grown to more than 80—largely because of “the responsibilities of war and empire.”

It wasn’t only the White House office staff that grew to meet the needs of an imperial capital on a wartime footing; the entire federal government grew, too, fattened on a network of new colonies and, by 1917, a true world-spanning war.

I think the true roots of the national-security state that the United States is today—the same subtle surveillance state that whistleblower Edward Snowden sought to describe—lie in the aggressive expansionism that characterized American policy between the McKinley and Woodrow Wilson administrations, between 1898 and 1918. Readers who came of reading age when Richard Nixon was US president from 1969 to 1974 may remember the charges of an “imperial presidency” being hurled at him and his administration, but in fact the charges were occasioned more by the trappings of power with which Nixon liked to surround himself. In truth, the nature of the American presidency began to change when McKinley decided to “Christianize” the Philippines, and make himself an empire in all but name.

At the turn of the century, one of the grand old men of McKinley’s own Republican party vigorously opposed the US policy of conquest. In one Senate speech, Sen. George Hoar predicted the consequences of American expansion. “Our fathers dreaded a standing army, but the Senator’s doctrine [he was referring to pro-expansion Sen. Orville Platt], put in practice anywhere, now or hereafter, renders necessary a standing army, to be reinforced by a powerful navy. Our fathers denounced the subjection of any people whose judges were appointed or whose salaries were paid by a foreign power; but the Senator’s doctrine requires us to send to a foreign people judges not of their own selection, appointed and paid by us. The Senator’s doctrine, whenever it shall be put in practice, will entail upon us a national debt larger than any now existing on the face of the earth, larger than any ever known in history.” Thus: a large standing army, a tradition of foreign intervention, massive debt-funded spending.

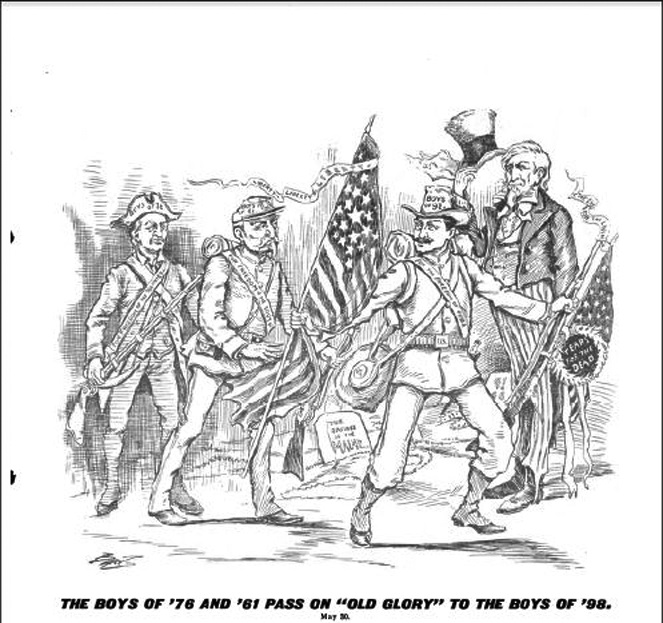

How did McKinley and the other expansionists square the idea of expansion, to the extent of subjugating other peoples, with the founding principles of the American Revolution? By linking the war against Spain in 1898 and later the conquest of the Philippines with the revolution of 1776 and the American Civil War. The cartoon (by the artist “Bart,” who drew it for the Minneapolis Journal on May 30, 1898) just about sums it up.

* * *

jnery@inquirer.com.ph