Biochar making

With many Filipinos still dependent on agriculture, the government faces the challenge of reviving the sector that has posted sluggish growth over the past several years.

Agriculture is also suffering from a degraded environment partly caused by chemical use in farming.

At the first National Conference on Philippine Biochar on April 17, agriculture experts and government and private sector representatives proposed a way to improve soil fertility—biochar, or agricultural waste transformed into organic fertilizer.

Article continues after this advertisementThe carbonized rice hull (CRH), a type of biochar, is an example of a product of the partial burning of rice hull. Instead of turning the outermost cover of rice grains into waste, it can be carbonized and turned into soil fertilizer.

Biochar, or charcoal from biomass, is a substance made from the incomplete combustion of biomass materials. It is produced when agricultural wastes, like rice hulls, wood chips, grass or leafy greens, and dried trunks or twigs, undergo a special cooking process that traps carbon dioxide (CO2).

Biochar is not for energy use but for soil regeneration and carbon sequestration. Biochar, when added to the soil, stays for thousands of years.

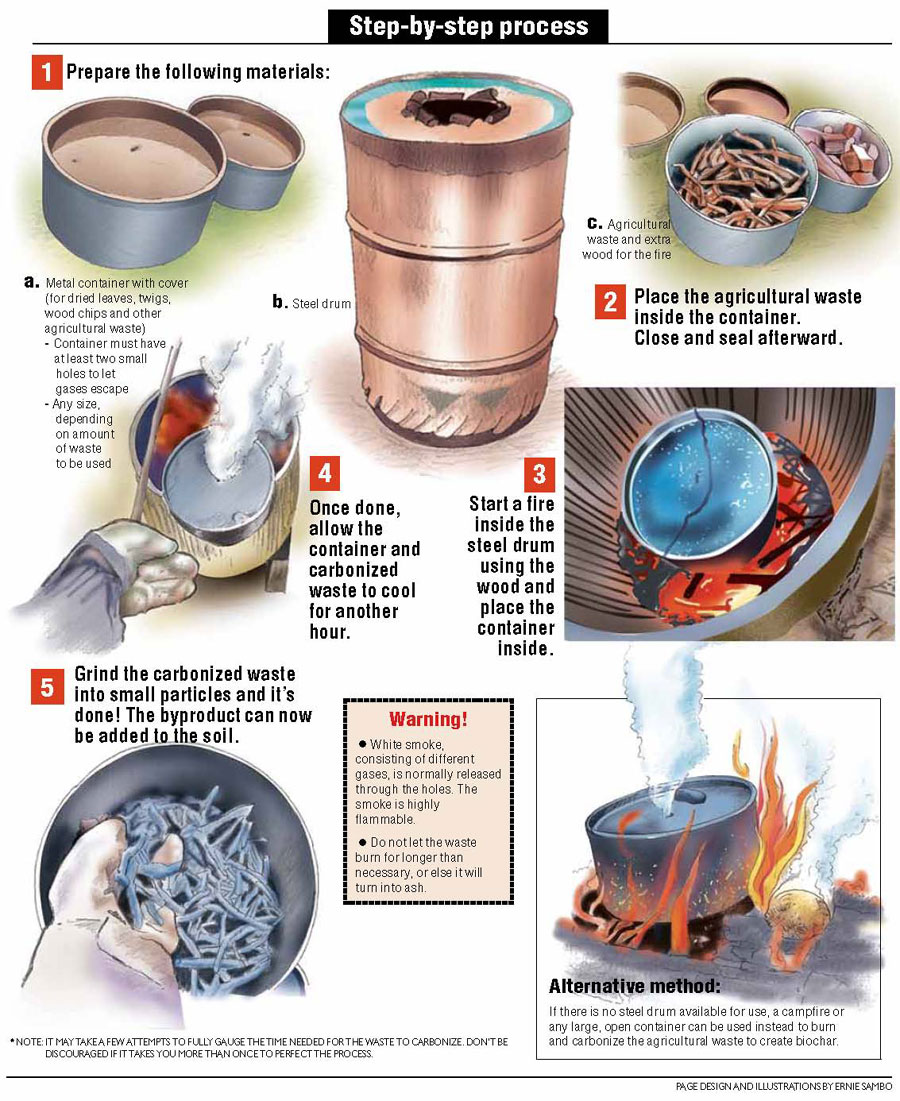

Farmers can use biochar as an alternative to chemical fertilizers. But biochar is not limited to farmers and the agriculture sector. Anyone can create biochar from scratch. Below is one easy method of making your own biochar at home.

Benefits

Boosts soil fertility. Once added, trapped CO2 is released to the soil, increasing the amount of nutrients soaked up by crops.

Article continues after this advertisementImproves overall soil quality. It traps more moisture in the soil, allowing for more beneficial microbes to be absorbed by crops and thickens the density of the soil to make up for lost nutrients due to continuous farming. It also lowers soil acidity.

Organic waste management. Creating biochar is a more environment-friendly way to dispose of agricultural waste than simply throwing it away.

Biochar in PH

Biochar, while not new to the Philippines, has not fully permeated the agriculture sector.

The Philippine Biochar Association (PBiA) is the first nongovernment organization (NGO) to advocate the use of biochar from carbonized rice hulls by farmers and local government units.

“Our program is working with small farmers so that their waste from their products become their raw materials,” said PBiA president Philip Camara.

According to PBiA, research shows that farmers’ yield increases by at least 10 percent through the use of biochar instead of chemical fertilizers.

PBiA acts as the medium between farmers and local government units. Together, each “local biochar network” could empower the farming community to use its “waste” to increase profits and to protect the environment.

PBiA is a member of the International Biochar Initiative, which promotes different methods of using biochar.

Farmers’ perspective

Even before biochar was introduced to Filipino farmers, there was already organic farming.

Arturo Dologmandin, president of Maligha Irrigators Association, said that as a child who grew up on a farm, he saw the transition from organic to chemical farming.

Dologmandin said that some farmers in Zambales opted to use chemical fertilizers because they wanted to improve rice production and increase their income.

It has been almost three years since they began using biochar after they learned about it in seminars given by the Department of Agriculture and NGOs.

“Now that we have realized the harmful effects of chemical fertilizers on our environment, especially now that our climate has been changing, we’ve started to change our ways,” he said.

Like Dologmandin, Daniel Villanueva, president of the Federation of Irrigators Association-Bucao River Irrigation System, said his group “gradually lowered” the use of chemical fertilizers in Botolan, Zambales, after PBiA introduced biochar to the association.

“We (farmers) were told that biochar was cheap. We also read a study that it reduces the use of chemical fertilizers that will help control global warming,” he said.

While it is impossible to fully transition to biochar at the moment, Botolan farmers have steadily reduced their use of chemical fertilizer, according to Villanueva. From 12 bags of chemical fertilizer per hectare, it was reduced to six bags after two years.

“Every year, we lower it by 20 percent. Now, we’re in our second year. We have decreased the use of chemicals by 40 percent,” he said.

Villanueva said that biochar was cheaper than chemical fertilizer since in their case it was made from rice hulls and easier to create because the process was straightforward.

“When you make one today, it’s already ready the following day. It’s so easy,” he said.

Dologmandin and Villanueva believed biochar could also address farmers’ financial problems.

Biochar is more cost-effective than and an organic alternative to chemical fertilizers. After an initial investment in equipment, a farmer can create biochar up to three times a day.

According to the Bureau of Agricultural Statistics, prices of different fertilizer grades ranged from P766 to P1,249 per 50-kilogram sack as of February.

Biochar also has positive environmental effects. Dologmandin said that climate change, global warming, diseases and a decrease in lifespan because of chemical intake from the food coming from plants could be addressed with biochar.

State support

At the biochar conference, various government agencies pledged support for the biochar movement not only as a means of uplifting the agriculture sector but also as a means of aiding farmers.

Edicio de la Torre, consultant for the agriculture department and member of its Technical Assistance Group, said, however, that the challenge was not in the technology but in how to promote its use.

“We do not need biochar to attain self-sufficiency. But we need biochar to sustain it,” he said. “And the key is, of course, the farmer, the human. The one who actually plants and harvests is the farmer.”

Agrarian Reform Undersecretary Jerry Pacturan said the government could not ask farmers to use biochar exclusively. The Department of Agrarian Reform (DAR) could promote it only as a green alternative to chemical fertilizer.

But Director Portia Lapitan of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) expressed hopes that more farmers would be open to the idea of biochar.

“Biochar is not widely used yet because we have not fully convinced the majority of our farmers to use them,” she said.

It was because of this that the government needed help from the private sector and NGOs to educate farmers on a wider scale.

“At the end of the day … the decision-makers are the small farmers,” said De la Torre. “We’re there to provide the necessary measures so that they are able to make those necessary decisions.”

Scaling up

But the challenge, he said, was “scaling up.”

Lapitan said that in Laguna, the DENR’s Ecosystems Research and Development Bureau had come up with a sample plant to showcase the creation of biochar.

A similar effort has been done in Zambales, where Botolan farmers have opened up a demo farm.

The Philippine Rice Research Institute has been implementing since 2001 the use of biochar, which it calls “carbonized rice hull.”

But attendees of the conference agreed that more was needed to be done and that continued partnership was the key.

Pacturan said a number of companies had partnered with the DAR to provide agro-extension, technology and marketing support to farmers.

But what’s more important for farmers, Villanueva said, was that their shift to biochar also safeguarded the land for their children and future generations.

“We’re not the only ones who can benefit from this,” he said. “We’re the ones who make it, so we’re the ones who know its use and its [positive] effects [on the environment].”