“The AFP, after thorough deliberation, has validated and confirmed … the sighting of two unidentified jet aircraft in the vicinity of the Kalayaan Island Groups in the Western Philippine Seas Wednesday,” a statement from the Armed Forces read. The statement clarified that the aircraft did not take any action that could be interpreted as hostile. There “could not have been provocation,” the AFP said—except that the intrusion itself was provocation enough.

While Reed Bank is not itself in dispute, the Kalayaan Islands or the Spratlys further west are very much in the center of a claims controversy, with several countries, including China, Vietnam, Malaysia and the Philippines, claiming part or all of it. And while other countries have not been shy about establishing physical, military presence in the disputed areas, China has been the most assertive. It is only to be expected, therefore, that when news about the reported intrusion spread, China seemed to be the likeliest culprit. And we repeat: It doesn’t seem possible that such an intrusion could have been allowed without express authorization from higher-ups.

Chinese Defense Minister Liang Guanglie directly addressed the issue during his Manila visit, which ends today. As the Associated Press reported: “Liang, according to Gazmin, mentioned that Philippine media accounts identified the two aircraft as Russian-made MIG fighter jets and clarified that China has no MIG planes in its air force.”

Perhaps there are no longer working MIG planes in the Chinese air force; perhaps the Philippine OV-10 pilots who sighted the fighter jets misidentified them. This is a detail that is subject to verification. There should be no question, however, that China in recent years (and contrary to its avowed emerging-superpower policy of a “peaceful rise”) has become increasingly assertive in pursuing what it calls its historical claim to the Spratlys.

As President Aquino himself noted the other day, the Philippines has recorded “many and different sightings and various other vessels” under the Chinese flag in the disputed areas. Just last March 2, two Chinese Navy ships harassed a Philippine oil exploration ship near Reed Bank. The Philippines later filed a formal protest with the United Nations.

(The very notion of a historical claim should be thoroughly questioned, since its reasoning would place a now completely independent country like, say, Vietnam under that over-broad Chinese policy.)

The timing of the visit of Liang, the man in daily charge of the world’s largest standing army, is of some moment; it comes just a few days after the powerful American carrier strike group led by the USS Carl Vinson, after burying the remains of al-Qaida founder Osama bin Laden, stopped over in Manila—a vigorous sign of US force projection into a zone of influence that China wants increasingly to call its own.

The official outcome of his visit is even more important: Liang and Gazmin issued a statement promising to avoid “unilateral actions” that would heighten the Spratlys dispute. (The statement, in truth, can also be read as a warning to other claimants to avoid similar actions.) This is a useful reaffirmation of the spirit behind the Code of Conduct, the 2002 agreement entered into by China and the Asean member-states.

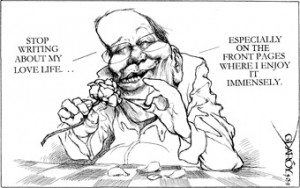

But we must point out the uncomfortable truth: Tensions over the Spratlys in recent years have been the direct result of China’s muscle-flexing. The harassment, the intrusion, the assertive language have all been coming from one side. The Chinese call for “restraints,” therefore, strikes us as a little like the schoolyard bully, under watchful eyes, making nice.