WORKERS assemble micro-motor fans for computers at the Sanyo Denki plant in the Subic Bay Freeport Zone. AFP

Secretary General Jose Ramon Albert of the National Statistical Coordination Board reported that poverty incidence remained unchanged between 2006 and 2012.

While the country’s gross domestic product (GDP) expanded an impressive 6.6 percent in 2012, a high and sustained pace of growth is crucial to generate substantial poverty reduction. To be sustainable, this growth should be broad-based across many sectors and inclusive of the large part of the labor force.

The conditional cash transfer program of the government should be accompanied by an inclusive growth strategy for sustainable growth and poverty reduction.

Jobless growth

We need an inclusive growth model in which the industrial sector, particularly manufacturing, plays a key role in generating investment, employment and innovation. As Josef Yap, president of the Philippine Institute for Development Studies, said there are more high-productivity, high-paying and quality jobs in manufacturing.

While the services sector has provided a major source of value added and employment in the past two decades, since the mid-2000s, the average unemployment rate has remained high at 7.6 percent while underemployment has stayed high at 20.14 percent. Though the country’s economy has expanded, its impact on employment creation has been characterized as jobless growth. (See Table 1.)

Revive manufacturing

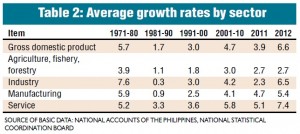

To lead the country’s sustained and high growth level, manufacturing needs to be revived given its weak performance in the past two decades. From the 1980s up to the early 2000s, manufacturing growth was slow, averaging 0.9 percent in the 1980s and 2.5 percent in the 1990s. Modest growth was posted in the 2000s with an average of 4.1 percent. (See Table 2.)

The average share of manufacturing in total output dropped from 28 percent in the 1970s to 26 percent in the 1980s and to 24 percent in the 1990s up to the 2000s. In terms of employment contribution, the manufacturing industry failed in creating enough employment to absorb new entrants into the labor force as its share of total employment declined from 11 percent in the mid-1970s to 9 percent in the 2000s. (See Tables 3 and 4.)

Development progeria

It is evident from the foregoing that the trade reforms of the 1980s did not transform the agriculture-based economy into a manufacturing-based economy and did not lead to rapid industrial growth.

According to Raul Fabella, a national scientist, the economy is suffering from development progeria or premature aging. This is manifested by the rise in the share of services and a fall in the share of industry and manufacturing sectors. While our neighboring countries registered substantial increases in the share of industry, the share of industry in the Philippines declined and remained stagnant.

Exports less diversified

The Philippine manufacturing export base has become less diversified as our exports are largely concentrated in three product groups consisting of electronics, garments, and machinery and transport equipment. Within these major product groups, exports are highly concentrated in low value-added and labor-intensive product sectors that are considerably dependent on imported inputs and have weak backward and/or upward linkages with the rest of the manufacturing industry.

In terms of the product space, Dr. Norio Usui, Asian Development Bank senior economist, characterized the Philippines as hollow since most of our products are in the periphery, like natural resources, primary and agricultural products, and very few are in the core area.

At the core of the product space are capital-intensive machinery, chemicals and metal products. Successful countries are dense at the core. In the Philippines, our product structure has many empty spaces at the core since it is largely dominated by weakly linked products in the periphery.

The industrial structure, measured by firm size or number of workers, has also remained hollow, with a very small proportion of small and medium enterprises (SMEs). The linkages between SMEs and large enterprises have also remained weak. SMEs have continued to face competitiveness problems and are continuously beset by difficulties in financing as well as technology and market access.

Most binding constraints

The lack of infrastructure and weak investor confidence arising from governance issues and weaknesses in the larger regulatory environment and investment climate are the most binding constraints affecting industry growth and entry of new firms.

Firms continue to face major constraints such as poor infrastructure and logistics; lack of domestic raw material suppliers, parts and components; bureaucracy, red tape and policy inconsistency; and lack of highly skilled workers.

Smuggled products

At the same time, domestic manufacturers have continued to suffer from the unabated entry of smuggled and substandard products and from high power and logistics costs.

Broken linkages in the supply/value chain characterize many of our industries. The lack of materials processing has severely affected the competitiveness of the Philippine parts and supplies industries, and hampered the ability of high-technology industries to move up the value chain.

Weak backward links

Due to weak backward linkages within the manufacturing industry, automotive and electronics have continued to rely on imported parts and remained at the assembly stage of the supply chain.

In the iron and steel industry, which is critical for the manufacture of parts and equipment, competitiveness issues have remained due to the high cost of raw materials (apart from the high costs of power and logistics, unabated smuggling and limited government capacity to monitor product standards).

The local tool and die industry has to compete heavily against imported dies and molds while its backward linkages are weak due to the unavailability of most raw materials, equipment and software.

Special steel and casts, general and specialized metal machines, and software are all imported. Labor is the only component of the value chain that is locally sourced. Though the country has natural resources that can provide important metals like iron and copper, there are no processing plants (capital-intensive blast furnace and steel-making facility) that would produce the form of metal that the industry requires. There is no reliable aluminum-casting facility for molds used in molding large plastic components like refrigerator liners.

In the export-oriented copper industry, firms have hardly any linkage with the domestic economy. Copper ores are all exported and although the country has a copper smelting facility, it imports 100 percent of its copper-ore requirements and exports 100 percent of its output due to the absence of a copper-rod facility. Manufacturers of wiring harness, a major export product and user of copper rods, import all of their copper-rod requirements.

New industrial policy

Given its popularity and high trust rating, the Aquino administration is expected to continue implementing solid reforms to overcome the difficult challenges in realizing the country’s potential. Now seen as a new growth area, the Philippines is well positioned to attract investments that would catalyze growth and development.

The government needs to capitalize on our recent investment upgrade to attract more foreign direct investment. Large market opportunities for our industries are offered by the Asean Economic Community market of 600 million people. At the same time, the rising costs in China, and the calamities in Japan and Thailand that hit industry supply chains have driven investors to look for alternative investment sites.

Lay foundation

A new industrial policy is needed not only to generate jobs and reduce poverty but also to take advantage of these market opportunities. To lay the foundation of becoming a major growth driver, upgrading technology and transforming the manufacturing industry are required.

Industrial policies are crucial in enhancing firm productivity, deepening linkages of domestic firms and SMEs with large domestic and multinational companies, and aggressively courting more investment. Policies will also be necessary to boost the survival of new entrants and provide assistance for the growth and development of SMEs.

To enable firms to move up the technology scale, programs should be formulated to improve technological and human-resource capabilities as well as to strengthen supply chains. For these to be effective, infrastructure, logistics, governance and regulation issues must be addressed.

Learning by doing

In the short run, the policy focus should be on strengthening and rebuilding existing capacity of industries especially those with strong potential to generate employment, address missing gaps, and create linkages and spillover effects in sectors such as automotive, electronics, food, garments, motorcycle, shipbuilding, chemicals and allied or support industries. During this initial stage, policies and programs should aim at exploiting economies of scale and learning by doing.

In the medium-term and as domestic capacities are reached, efforts in the initial stage should lead to expansion and new investments, especially in the upstream, intermediate or core sectors such as iron, steel and other metals as well as in parts and components industries.

By linking manufacturing with agriculture, construction, mining and services, supply-chain gaps will be addressed and forward and backward linkages strengthened.

In the long run, a globally competitive manufacturing industry with strong forward and backward linkages is envisioned as the Philippines plays a vital role in the regional and international production networks of automotive, electronics, garments and food. (See Figure 1.)

While the private sector is seen as the major driver of growth, the government has an important role to play in coordinating policies and support measures that will address obstacles to the entry and growth of domestic firms.

In the short run, the granting of hard industrial policy measures like fiscal incentives is not the most binding constraint affecting the growth of most industries.

Industry analysis and consultations show that close coordination among government agencies and effective policy implementation are the most crucial factors for industry development. Implementation of legislation; strict enforcement of product quality standards; measures providing access to raw materials, intermediate inputs and common service facilities; and aggressive investment promotion and marketing to attract investments are some of the immediate measures that the present administration can put in place.

Recommendations

Address gaps in industry supply chains.

Expand the domestic market base to allow industries to attain economies of scale and to export.

Design human resource development and training programs to improve skills, and establish tie-ups with universities and training institutions.

Support SME development through the establishment of common-service facilities and innovation, and R&D activities.

Pursue aggressive promotion and marketing programs to attract more foreign direct investments, especially those that would bring in new technologies.

Continue to address the high cost of power and domestic shipping, smuggling and implementation of measures to streamline and automate government procedures and regulations.

By creating the proper environment and strengthening industries to ensure that they are not disadvantaged by international competitors, the government can promote the success of domestic firms in both the local and international markets that will lead to economic transformation.

Only with the right environment can manufacturing unleash its full potential to take advantage of market opportunities and become an engine for sustained and inclusive growth, job creation and poverty reduction.

(Rafaelita M. Aldaba is vice president and senior research fellow, Philippine Institute for Development Studies.)