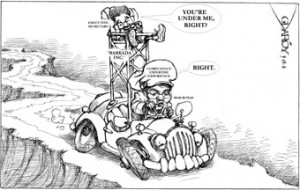

YESTERDAY, SUPREME Court Chief Justice Renato Corona marked one full year in office—a milestone he observed dutifully with, among other appointments in a busy week, a few revealing media interviews. His main purpose, as far as we can tell, was to reassure the general public that the Corona Court is both independent (not beholden to the previous president) and responsive (not obstructionist in its treatment of the policies and the politics of the current one). The Filipino people must know, Corona said, that “they have a Supreme Court they can trust.”

That is a consummation devoutly to be wished but, as far as the judiciary is concerned, what does trust consist of? It consists entirely of doing justice, and being seen doing it.

Corona is surely right to say that “My job is to decide cases fairly, according to my conscience, the Constitution, the law. No personal feelings, emotions involved.” But it is a measure of the distance Corona himself sees between the legitimacy of his appointment (something this newspaper together with many others in civil society argued against last year, but is now settled by Supreme Court fiat) and the legitimateness of the criticism against his appointment that in marking his first year in office, he finds himself bringing “personal feelings, emotions” into the picture.

He talks of going the extra mile to accept the criticism with grace: “I have been ultra-patient, ultra-forgiving and I think, ultra-Christian, in the way I have conducted myself. You should not be onion-skinned in a job like this.” He dwells on the fundamental loneliness of high office: “When you are at the helm, you all of a sudden have to be sensitive to many things, like criticisms, demands for justice, the constituents think that you are [lacking] so you try to improve on those areas. These responsibilities, there’s no one to pass the buck now. The buck stops here.” He speaks of the existential dilemma of the poor and the aggrieved who reach out to him. “When you read these letters from these people, it’s the human side of you that takes over and it’s not easy emotionally. Somehow, you empathize with them, their problems. There’s no money, food, or justice.”

He also denied being personally very close to Gloria Arroyo, whom he served at various times as presidential chief of staff, official spokesperson and acting executive secretary. Again the main explanation he offers for his first appointment as associate justice turns out to be neither policy-driven nor politically strategic, but only personal.

“… If I was really very close to her, I would not have asked to be appointed to the Supreme Court. I asked to move out of Malacañang”—because it was, he said, a snake pit.

The personal, even emotional answers are not entirely convincing. (The unflattering “snake pit” image, for instance, does not answer the question why he was appointed chief justice years after escaping the Palace.) But then we understand them as not actually meant to convince but only to persuade, with the connotative language of sacrifice and forbearance and empathy. The message is, the man who will serve as chief justice until 2018, or two years after President Aquino leaves Malacañang, is a practicing Christian and a true gentleman, a patriot who, despite criticism, will do right by the public.

Except for a few words about how certain decisions of the Court could be construed as unfavorable to Arroyo, Corona did not really discuss his judicial philosophy, or explain why—to give only one example—he chose to fight Malacañang so aggressively on the judiciary’s budget. (The assertiveness of the Corona Court was startling, because surely a mere budget proposal, even if it is that of the judicial branch, does not enjoy constitutional protection.) In other words, Corona’s term has not all been passive, a patient taking of the Executive’s blows. Also (to give a second example), the reasoning behind the junking of the Truth Commission is law devoid of human context—the very context Corona immerses himself in when he reads those pained letters from the public.

Both the Aquino presidency and the public have had no choice but to come to a modus vivendi with the Corona Court. The Chief Justice’s first anniversary interviews suggest that there may be a more responsive court in the future. But the axiom remains: The proof of the pudding is in the eating.