How Maguindanao and Cotabato rulers helped Sulu win Sabah

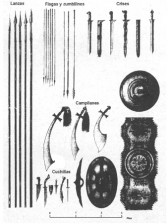

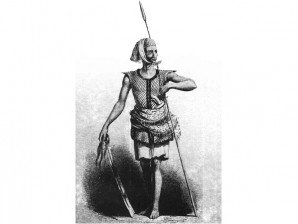

AN IRANUN sea raider, attired in cotton-quilted vest and armed with a spear, kris and “kampilan” decorated with human hair. The Iranuns were subjects of Sultan Kudarat. PHOTO BY James Francis Warren, “Iranun and Balangingi: Globalization, Maritime Raiding and the Birth of Ethnicity.” 2002

The Sultanate of Maguindanao and the kingdom of Buayan in upper Cotabato played key roles in ending a civil war in Brunei in the 17th century that resulted in the Sulu sultanate being rewarded a huge swath of territory called Sabah.

Reinforcements from the sultanates in Mindanao tipped the balance in favor of the Brunei leader, who had sought the help of the Sulu sultan.

Article continues after this advertisementThe royal houses of Brunei and Sulu had kinship ties even before the civil war.

Intermarriages

One can begin with the sister of Brunei Sultan Sheif ur-Rijal, the seventh sultan who ascended the throne in 1578, getting married to the Sulu ruler.

Article continues after this advertisementThen there was the report of Spanish chronicler Antonio Pigaffeta that Brunei’s Rajah Siripada was married to a daughter of the king of Sulu.

Citing the selesilah (genealogy) of Brunei, Muslim-Filipino scholar Cesar Adib Majul said that Sultan Bulkeiah, who took Sulu Princess Leila Men Chanei as his wife, “was likely the sultan titled Rajah Siripada when Pigaffeta arrived in Brunei in 1521.”

One of the royal couple’s sons whose title was Pangiran Shahbander (Prince of the City) left Brunei “because he did not rank with the other children of his father.” The prince “eventually became Batara Rajah, that is, the ruler of Sulu,” Majul said.

Closely similar to the title Batara Rajah is Batarasa or Batara Shah Tengah, identified in the Sulu genealogy as the ruler who would be the immediate predecessor of Sultan Mawallil Wasit Bungso, who assumed the sultanate in about 1610.

Sulu sultan’s 2 daughters

Sultan Wasit, also known as Rajah Bungso, had two daughters—one was married to Sultan Muhammad Dipatuan Kudarat of Maguindanao and the other to Rajah Balatamay, king of Buayan in Upriver Cotabato.

According to Majul, Sultan Kudarat (reign: 1619-1671) was the contemporary of both Bungso and his son, Sultan Salah ud-din Bakhtiar, the Sulu ruler during the 10-year Brunei civil war, which started in 1662 or earlier.

The relationship between the Sulu and Maguindanao Sultanates can be easily appreciated in a diagram in Majul’s book “Muslims in the Philippines,” which partly integrates the genealogies of Sulu and Buayan into that of Maguindanao, as traced from cases of intermarriage.

Koxinga threat

Of great significance to political developments in the south was the May 1662 arrival in Manila of a Chinese emissary in the company of Dominican Vittorio Ricci from Formosa. The emissary was carrying a letter from Koxinga, who earlier seized Formosa from the Dutch. Koxinga said he would attack Manila if the Spanish authorities would not pay him tribute.

Under threat of invasion by Koxinga’s thousands of ships and men, the Spanish government in Manila made hasty efforts to build up its defenses. On Nov. 8 of the same year, Spanish Governor Fernando de Bobadilla of Zamboanga was instructed to leave the fort to Christian Samals and send its forces back to Manila.

“The situation was such that it appeared imperative to recall the garrisons assigned to various parts of the Philippines and the Moluccas, and concentrate them on Manila,” Majul said.

Brothers-in-law

At this time, some Sulu datus were raiding islands in the Visayas while Sultan Bakhtiar tried to convince his brothers-in-law Sultan Kudarat and Rajah Balatamay to join him in recapturing the Zamboanga fort.

Kudarat refused to cooperate, arguing that the fort would fall anyway into his hands by default sans the Spanish forces.

Trade with Dutch

To Kudarat, reviving trade ties with the Dutch in Borneo was of bigger interest to the sultanates in such a period of much-needed respite from decades of war after he suffered defeat in Lamitan, Basilan in 1637 and the Sulu Sultan’s defeat in Jolo in 1638 at the hands of the Spaniards under Sebastian Hurtado de Corcuera.

Kudarat prevailed on Bakhtiar not to attack the Zamboanga fort.

Brunei sultan’s call for help

It is said that Brunei’s Sultan Muaddin wrote the Sultan of Sulu requesting military assistance and promising that “from the North to as far West as Kimani would belong to Sulu.” (Hugh Low, “History of the Sultans of Brunei,” 1880.)

After the 1662 killing of Muhammed Ali, the 12th sultan of Brunei, by Bendahara Abdul Mubin and his followers, Mubin assumed the sultanate. But Mubin was denounced by his cousin Pangiran Bungso as a “usurper.” Pangiran Bungso was proclaimed Sultan Muaddin.

Famine, trade blockade

Muaddin was under pressure to resolve the conflict with Mubin as there was famine in Brunei and trading boats were being blocked by those holding Pulao Chermin, the island base of Mubin. The island was close to the mouth of the river in Brunei, according to Majul.

In that sense, clearing the trading routes was a common interest, if not of greater significance, to the sultanates of Sulu and Maguindanao than the promised reward to the Sulu Sultanate.

Sultan Kudarat’s letter

Maguindanao’s free trading with other islands in what is now Malaysia once met “the wall of Dutch commercial monopoly.” To illustrate this, wrote Majul, Sultan Kudarat on April 3, 1661 sent a letter to Dutch Governor Hustart in Amboina, asking that his vessels be allowed to frequent the island for trade.

A Dutch hand in the trade route blockade was not entirely improbable, because there was a time, according to Majul, when it became difficult for Maguindanao to export rice, since it appeared that the Dutch did not approve of it within the sphere of their influence.

Kudarat managed to revive Maguindanao’s economic relations with the Dutch on a promise that the sultanate would not engage with other Europeans in wax trading.

Moro warriors

Lawyer-historian Datu Mama S. Dalandag said there was a confluence of Iranuns under Kudarat, hundreds of warriors from Cotabato upriver under Balatamay and the Sulu followers of Bakhtiar who dealt with those blocking the sea trade lane at Pulao Chermin.

[Dalandag is the modern-day author of the Buayan kingdom tarsila (genealogy) and former dean of the law school at Notre Dame University in Cotabato.]

Kudarat left Bakhtiar and Balatamay with some 900 warriors and proceeded toward the boundary of the north and south Borneo, effectively keeping at bay the peril of the conflict spilling over to a region where the Sultanate of Ternate shared influence with the Dutch.

A Brunei selesilah version that the foreign forces merely stood by and watched didn’t seem to be entirely baseless.

Under Sulu command

But by Dalandag’s reckoning, Rajah Balatamay joined his brother-in-law, Sultan Bakhtiar, and at times, the joint forces of Sulu, Cotabato and Maguindanao were placed under Bakhtiar’s command in the battle that suppressed the group of Mubin.

Traditionalists believe that no sultan would have decided to do the rescue just because of a promised material reward. Far from personal interest, Muslim leaders would usually make decisions on the basis of greater public interest under the doctrine of istislah (literally, deemed proper) in Muslim jurisprudence.

The khutba salawat (prayer for the Prophet and his family, including the sultans who are believed to be his descendants) records the personal attributes and characters of the sultans, who were endowed with prudence and knowledge, including sharia (law) and fiqh (jurisprudence), according to this traditional source.

For instance, Sultan Kudarat’s decision to revive trading activities with another European power, in the absence of the Spanish forces that were recalled to Manila’s defense against the Koxingan threat, was a more practicable option to the sultanates than waging war against local converts to Christianity in order to retake their former subjects from the Spaniards.

Iranun in Borneo

Many of Kudarat’s Iranun warriors stayed behind after the civil war in a settlement ceded to Maguindanao by the Sultanate of Ternate in grateful appreciation of his efforts in helping prevent the spread of the family conflict to south Borneo.

Evidence that supports this version is the presence of Iranun-speaking people in some present-day Indonesian and Malaysian territories in Borneo.

It is also probable that, instead of directly saying that a civil war had erupted from the ruling family’s feud, Brunei Sultan Muaddin may have partly misinformed the Sulu Sultan that a mutinous force, backed by a restive generation of settlers, was adversely affecting common economic interests in the region.

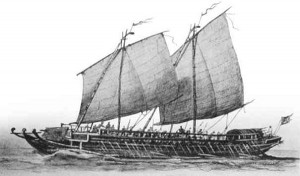

A “LANONG” (“joanga”) is an Iranun warship of the late 18th century with three banks of oars under full sail. At least 30 meters long, it was provided with large bamboo outriggers and rowed by more than 190 men. PHOTO BY James Francis Warren, “Pirates, Prostitutes and Pullers.” 2009

Knowing that he would be liable for violating the Muslim law with a half-truth, which led to the involvement of more parties in the bloodshed, Sultan Muaddin had to make the offer to recompense the Sultanate of Sulu.

Stewardship

Gov. Mujiv S. Hataman of the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao said there was no doubt that Sabah belonged to the Sultanate of Sulu.

Hataman, however, was quick to point out that the Sultanate of Brunei under Muaddin ceded the region to the Sulu sultanate and not to the Sultan of Sulu, “because there is no absolute land ownership in Islam; only stewardship.”

Hataman’s wife, Princess Djhalia Turabin-Hataman, would be an heiress under Muslim law from the genealogical continuity of the 1939 Macaskie Decision (Kiram-Overbeck Lease of 1878).

Second Mawallil Wassit

In an abbreviated genealogy, there appears a second Mawallil Wasit, father of Datu Ponjongan and Sultan Ismael Kiram, among others.

It is said that the latter-day Wasit principally initiated in 1936 the question of hereditary rights for the family of the sultan before the Sabah High Tribunal of the Malay Federation under the British Commonwealth. The 1939 Makaskie Decision names the second Wasit’s descendants, among them Sultan Ismael Kiram and Datu Ponjongan, as heirs.

However, on Majul’s list of the succession of Sulu sultans as narrated in the khutba salawat, Sultan Nasiruddin II appears to be the 10th sultan before Pangiran Salah ud-Din Bakhtiar contested the rule of his father and became sultan in 1650, after the death of his brother Pangiran Sarikula.

Sarikula briefly held the throne before it reverted back to their father (Wasit Bungso). A joint-rule might be more appropriate for Sarikula and his father, according to Majul.

It is entirely plausible that Nasir ud-Din II refers to no less than Sultan Kudarat of Maguindanao, according to Majul. If this has to be relied on, Wassit Bungso in old age could have anointed his son-in-law (Kudarat) as the sultan emeritus, in his place. This was probably to provide the rebellious son with much-needed guidance in leadership and prudence in running the affairs of the state.

But why would Kudarat influence and prevail over the Sulu Sultan’s political plans in light of the political developments in 1662?

Sultan Kudarat’s prestige “was such that even in Sulu, he was respected to the extent of actually influencing its internal affairs,” Majul said.

Most powerful ruler

Majul wrote: “Kudarat was also titled Nasir ud-Din and around the 1650s had become the most powerful Muslim ruler in the Philippine archipelago.

“His declaration of jihad around this time could have endeared him so much to the ulama [learned men particularly in religious affairs] of different Muslim sultanates, including the Moluccas that they could have included him in their prayers.

“After all, there was heightened consciousness of Islam during this time that transcended regional and dynastic loyalties. Sultan Kudarat appeared to have been the Muslim ruler who was best able to hold his ground against the Spaniards ….”

The first Muslim Sultana, Pangian Ampay (Sultana Nur ul-Azam on Alexander Dalrymple’s list), was the daughter of Kudarat’s second cousin, Rajah Balatamay of Cotabato, by the daughter of Sultan Mawallil Wasit Bungso.

(Nash Maulana, a former correspondent of Inquirer Mindanao, is the director of the Bureau of Public Information of the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao.)