THE COMING royal wedding in Engla

nd

and the beatification of Pope John Paul II in Rome will afford the world a chance to see how two ancient institutions—the monarchy and the papacy—reinforce their claim to perpetuity and continuing relevance by a show of pomp and pageantry. Supposed to be historical rivals, especially considering their religious wars si

nce the 16th century, these two institutions have in the recent past have come to some form of rapprochement, preoccupied as they have been with the more basic issu

e of survival.

For the monarchy of the United Kingdom, the downsizing of the British empire at the start of the 20th century, culminating in the Hong Kong turnover in 1997, has been a continuing problematic transition.

It’s propitious that in the same year, Princess Diana died in a car crash. Her wedding to Prince Charles in 1981 had been billed as a magical fairy tale and provided hope that the British monarchy would survive the snowballing enervation of the modern era. But their subsequent estrangement dashed all the enchantment and optimism. In 19

92, when their separation was officially announced—along with the respective divorces of Charles’ siblings Prince Andrew and Princess Anne—Queen mother Elizabeth bitterly lamented on the 40th anniversary of her ascension to the throne that it had all been “an Annus Horribilis.”

But the very photogenic faces of Diana’s children, Princes William and Harry, that shone at the funeral of Princess Diana held out the hope that the monarchy would be rehabilitated. Because the private lives of the Queen’s siblings had embarrassingly embodied their respective variations of the emperor’s new clothes, it was generally believed that her grandsons by Diana w

ould harness their beauty, innocence and good sense to rescue the sullied monarchy and provide it a new spring, if not truly real new clothes.

And they have not disappointed. William and Harry have behaved well and avoided being fodder for the scandal-mongering British press. And on April 29, William will marry smart-looking Kate Middleton, rewarding the monarchy with the windfall of a romantic wedding. An opinion poll Monday by the Guardian newspaper, not exactly a supporter of the monarchy, showed 63 p

ercent of those questioned agreeing that Britain would be worse off without the royal family.

It’s expected that the monarchy would squeeze just about every publicity pulp from the wedding. It helps that the media as a culture industry have made of the monarchy a spectacle. The UK and the world population of those hoodwinked for everything royal constitute what the French thinker Guy Debord calls the “society of the spectacle,” in which all forms of human communication are replaced by the consumption of images. Meanwhile, those in the Third World avidly watching the royal spectacle would unwittingly experience the paradox of g

lobalization—as more borders fall with the ease of communication.

Another form of spectacle will ha

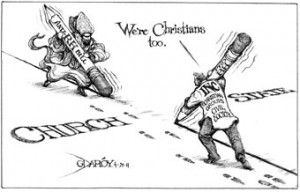

ppen in Rome on May 1, when Pope Benedict XVI beatifies his well-loved predecessor, John Paul the Great. Like the British royal family, the Holy See hopes that the celebration would help the Church burnish its image—badly damaged by pedophile priest scandals in the United States and Europe. But it’s remote whether the society of the spectacle would apply to the Church since spectacle and fetishization as forms of capitalist development hardly can be ascribed to an institution that has historically resisted unfettered capitalism and the more godless aspects of modernity.

“Spectacle” for the Church goes by the

name of liturgy, in which signs and symbols, linked with words, converge in congeries of meaning and value. And since the Church claims to be universal as to inc

lude not only all races and peoples living today, but also the Church triumphant in Heaven and the Church suffering in Purgatory, the beatification of someone who has passed on and universally acclaimed since then as among the heavenly elect is one spectacular show of all-encompassing communion, a truly border-less world, if there was one. At

the least, it’s a conceit that could only be granted to an institution that’s 2,000 years old and still thriving against all odds.