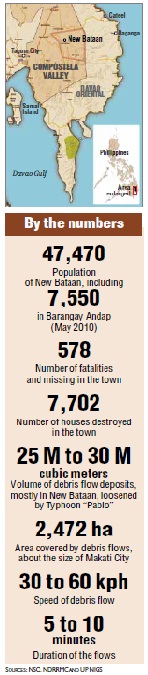

How debris buried Compostela village

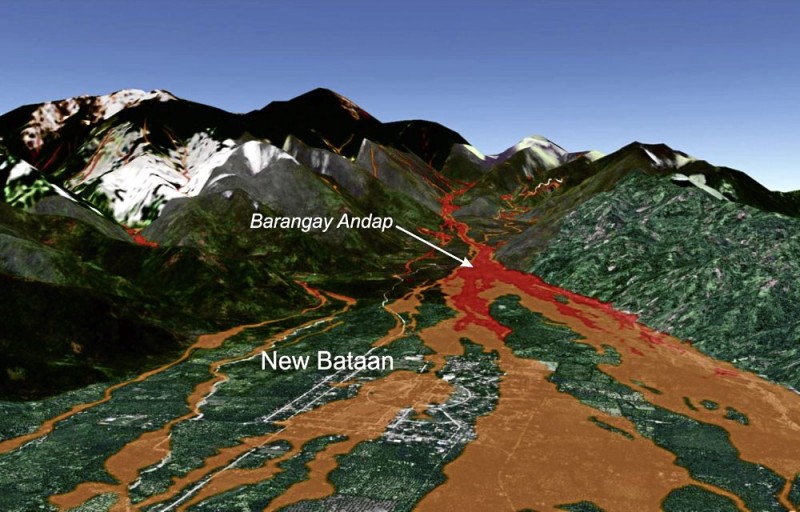

DEBRIS flows devastated Barangays Andap and Cabinuangan in New Bataan, Compostela Valley. Boulder-rich debris flow field (red) and sandy deposits (tan). The boulder-rich field is at least 7 kilometers long. Image courtesy of Sentinel Asia and CNES

On December 4, 2012, Typhoon “Pablo” (international name “Bopha”) made landfall in Mindanao. Classified as a Category 5 typhoon by US meteorological experts, Pablo packed winds with an average speed of 185 kilometers per hour (kph) and gusts reaching 210 kph. Pablo’s eye crossed Mindanao through Davao Oriental, Compostela Valley, Agusan del Sur, Bukidnon and Misamis Oriental.

It continued west-northwest to Negros Oriental, then to Sulu Sea, crossing Palawan before reaching the West Philippine Sea where it reversed course toward northern Luzon. It dissipated before making landfall.

Article continues after this advertisementDespite advanced warnings and preparations by communities, Pablo exacted heavy damage in Mindanao with 1,067 deaths, 834 missing and P37 billion worth of damage to infrastructure and agriculture.

Compostela Valley recorded the biggest number of deaths at 612. Davao Oriental saw 395 dead, mostly from the coastal towns of Cateel and Baganga, where the typhoon had made landfall. The municipality of New Bataan suffered 128 fatalities and 450 missing.

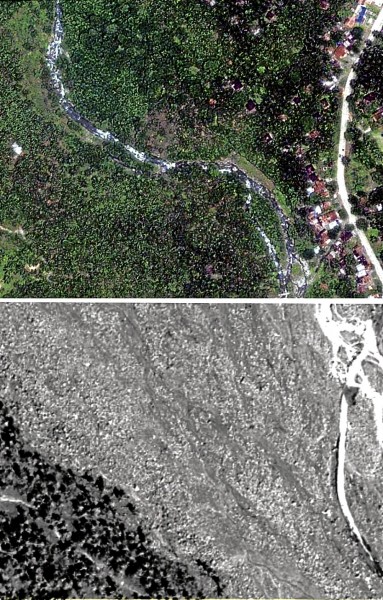

SATELLITE images of part of Barangay Andap before and after debris flows buried it. The first image was taken on Oct. 22, 2010 and the second on Dec. 12, 2012. Before photo from Google Earth, After photo from Sentinel Asia

Barangay Andap

Article continues after this advertisementBarangay Andap in New Bataan suffered the most, overwhelmed by a rapid downward moving mass of material that was fluid as wet cement. The mass was composed of boulders, gravel and sand. In its wake, it left a pile of rubble called a debris flow deposit. (See sidebar.)

Barangay Andap is at the mouth of a mountain drainage network at the base of steeply sided slopes and on the path of a debris flow spawned by intense rainfall during Pablo. (See infographic.)

30 million cubic meters

Satellite images and field work in New Bataan reveal a large amount of remobilized debris in Pablo’s aftermath. A total volume of 25-30 million cubic meters is estimated for the debris flow deposit, equivalent to the load of about 2.5-3 million 10-wheel dump trucks full of rocks.

The rubble was spread over a distance of more than 13 km and an area of 2,472 hectares, nearly as large as Makati City.

Most of the deposits were less than half a meter thick but in Barangay Andap, including an evacuation site where more than 200 people had sought refuge from floods, boulders piled up to as thick as 8-9 m.

The levee of rocks is characterized by gravel and sand at the base, which increases in size toward the top of the heap. The largest boulders in the debris field measure up to 9 m in diameter.

In interviews, residents of Barangay Andap, who saw the debris flow happen, narrated a short-duration event of 5-10 minutes at between 6:30 a.m. and 7 a.m. of Dec. 4.

Speed

Given the length of the deposit field and analysis of video footage at the onset of the event, the speed of the debris flow is estimated at 30-60 kph.

Scour marks in newly incised river channels, some reaching 5 m into the subsurface, reveal the highly erosive power of this flow.

Stacks of logs occupy streams and creeks in reaches where gravel and sand deposits dominate. In the center of the poblacion in New Bataan, a stream was clogged by clumps of fallen trees and was the site where dozens of dead bodies were recovered.

Old debris flow deposits

Similar but older debris flow deposits with the characteristic large boulders scattered on top of the debris field are found in Barangay Andap. This means that in the past, debris flows smaller in scale, but nonetheless significant, flowed into the municipality.

The rain record in the municipality of Maragusan, about 19.5 km southeast of Barangay Andap, reveals heavy (7-15 mm/hr) to intense rainfall (15-30 mm/hr) over a five-hour period from about 2:30 a.m. to 7:45 a.m. of Dec. 4.

Rains reached torrential values (>30 mm/hr) from 6:30 a.m. to 7 a.m., with the peak rain rate of 51.82 mm/hr occurring at 6:45 a.m. This is the kind of rainfall wherein the fastest wiper speed will fail to make a vehicle driver see the road.

Rainfall from 12 a.m. to 12 p.m. on the day of the disaster totaled 172 mm, mostly delivered during the early morning. Such rainfall intensity is within the initiation-threshold values of studied debris-flow occurrences in the Philippines, in particular those that happened on Mayon and Pinatubo volcanoes.

Contributory factors

Other contributory factors that led to the generation of debris flows may have been the strong winds of Pablo and the presence of the Philippine Fault Zone (Mati Segment).

Gusts reaching 210 kph uprooted hill slope trees in the 240-square-kilometer upper watershed area of New Bataan and lowered the absorptive capacity of the ground, which in turn triggered soil slips and erosion by storm-induced surface runoff.

Similar in terms of changing the absorptive capacity of a watershed to rainfall, forest and bush fires are known to lower the rainfall initiation thresholds for debris flows.

Fracturing, slides

The Philippine Fault Zone most likely contributed to the weakening of rocks through fracturing. This caused instability of the mountain slope that could have been easily triggered into rock slides and slumps by intense rainfall.

Numerous landslide scars were identified in the upper watershed where the debris flows originated. The material in these smaller landslides fed the debris flow mass that devastated Barangay Andap.

In Compostela Valley, landslides are often blamed on small-scale mining and the attendant destruction of the forest. However, New Bataan is the rest-and-recreation site of Compostela Valley.

No mining activities were observed in the mountainsides from the vantage point of Barangay Andap and the poblacion of New Bataan, validating claims by local officials.

Clearly observed is denudation of the forest and encroachment of coconut plantation fields.

Lessons

Mindanao has rarely experienced typhoons in the past, but they are now increasing in frequency and intensity. Pablo occurred only a year after Tropical Storm “Sendong” devastated the island, killing 1,268 people and causing P1.8 billion in damage to property.

Before Sendong, the last major event was Typhoon “Nitang” in 1984. The residents’ unfamiliarity with such intense cyclones in Mindanao, and the massive landslides and debris flows they generate is reflected in the large number of fatalities.

Decision-makers need a better understanding of these lethal phenomena and a sense of their increasing frequency in order to plan mitigation measures more effectively.

It is important to realize that a massive debris flow transforms the landscape. The next one can be expected to flow along paths other than the newly raised ground. The debris flow, which formed a new channel that passed directly through New Bataan proper, should be addressed before the next typhoon season.

Detailed hazard maps

Detailed, community-scale hazard maps are necessary, especially in view of the rapid growth of the Philippine population, which unavoidably expands into other areas, including possibly hazardous ones.

Regional-scale hazard maps are good only for regional planning; the specific siting of new communities requires rigorous evaluation of the hazards in a given area. Safe zones and access to them during emergencies need to be identified and prepared.

A developing country has difficulty funding mitigation measures and the best recourse is for individual families to develop an emergency plan. Such planning, of course, requires accurate, accessible, understandable and timely government input.

Hope

There is hope. Cagayan de Oro during Pablo was swamped by floods caused by a 6- to 7-meter rise in river water level. Despite the deluge, Kagayanons prevented a repeat of Sendong because they were well-informed and knew exactly what to do. Their model for mitigating natural hazards can be an answer to our disaster dilemma and needs to be replicated elsewhere without delay.

(The authors are scientists of the Department of Science and Technology’s Project Noah, and faculty members of the National Institute of Geological Sciences, University of the Philippines. Thirty references were not included in this version. They are available on request.)