Recent events are markedly different. There are no warlords to blame. Innocent children were the victims. The actions were random and nonreactive. Yet, the killing of children and the methodical slaughter of civilians in Caloocan City and Cavite cannot be removed from the long list of tragedies caused by the proliferation of guns in the country. It highlights the danger that lurks behind the licit and illicit firearms trade in the Philippines.

Firearms around us

Gun owners are not limited to law enforcers and macho men strutting about with pistols on their hips and rifles in their cars. They include single and married women who have increased their purchases in recent years. Other owners include politicians, government officials, judges and other judicial officers, actors and other celebrities, lawyers, doctors, academics, engineers, IT professionals and businessmen.

Most gun owners are genuinely afraid about their physical safety and the security of their assets. Few reside in enclaves with guards at the gates. Most keep their weapons at home. Many possess guns but have not trained these weapons on other human beings.

What divides them from the rest of us is their ability to procure firearms. An ordinary handgun can be purchased for less than P10,000. It costs P320 to get a license for a low-caliber pistol or revolver (cal. 22 or below) and up to P720 to P800 for higher-caliber guns.

Online, informal networks

One can even purchase guns from providers who advertise services online or via informal networks, which can facilitate the licensing and acquisition of a permit to carry.

Grey market, private hands

Most of the guns that leak into the grey market are in private hands. The illicit weapons in the hands of threat groups such as the New People’s Army or the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) or crime groups such as the Pentagon or Ozamiz gangs account for only a small fraction of the total number of illicit firearms.

A recent study by the author of the shadow gun economy reveals numbers that dwarf the official estimate of 1.1 million illicit guns. The evidence shows that there are at least 1,906,000 illicit guns in the country, or twice the number of the estimated legally registered firearms (930,000). Only 21,500 weapons are estimated to be in the hands of threat and crime groups.

Illicit guns at South Harbor

The evidence also debunks the myth about illicit weapons flowing to rebels and criminal syndicates from Danao in Cebu or the so-called “porous borders of the South.”

There are more chances to capture illicit weapons in Manila’s South Harbor. Most of the guns available in the country’s grey markets come from leakages in legal imports and government procurement. Illicit weapons are not tied to smuggling operations in the South, but to the formal import and export business in the North.

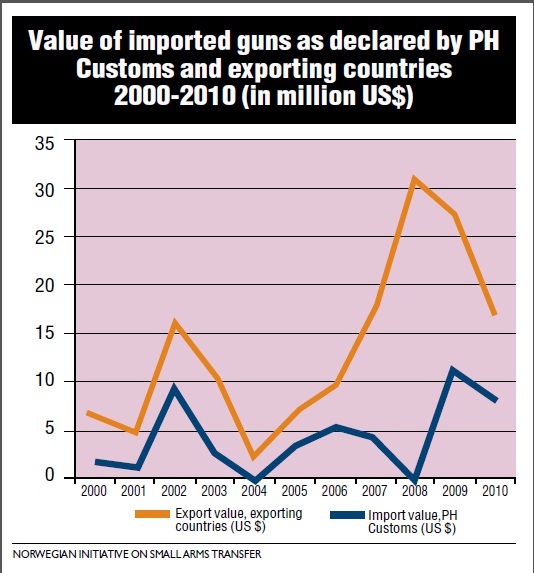

Philippine Customs data monitored by UN Comtrade and the Norwegian Initiative on Small Arms Transfers show that the Philippines imported 265,149 guns valued at $90.9 million from 2000 to 2010. These are dwarfed by the sales documents of exporting countries that show the Philippines actually importing 434,999 guns valued at $182.9 million from 1996 to 2010.

The discrepancy, 169,850 firearms costing $92 million, leaks into the grey market. The corresponding loss of revenue is quite significant. (See chart.)

The Philippines is a well-known exporter of firearms. A snapshot of export data from 2005 to 2010 indicates that the Philippines exported 1.6 million guns (classified as pistols and revolvers, sporting and hunting shotguns, and sporting and hunting rifles) to various countries in North America, Southeast Asia, the Middle East and Africa.

These are not your Danao-made knock-offs of foreign brands. They include the weapons and ammunition manufactured by Armscor that supplies such clients as the Thai police force.

However, the export data as recorded in Customs receipts are similarly at variance with the import data of recipient countries. From 2005 to 2010, Philippine Customs recorded a cumulative number of 89,056 pistols and revolvers exported to the United States valued at $4.5 million.

Yet, Customs records in the United States recorded a higher number of 143,343 units valued at $29.8 million. The six-year import data of the United States reveal an average annual under-reporting of 40 percent in the number of guns and 85 percent in value.

Criminalization of State

All this points to a glut in weapons within the country’s borders that could be harnessed by the State if it genuinely trained its sights on seizing the loose firearms controlled by criminal groups and politico-military elites.

It also exposes a shadow gun economy that is not completely outside the administrative and political reach of the State. The persistence of this shadow economy depends at first instance on the agents of the law rather than the illegal traders and manufacturers outside the law.

The implications are startling—it suggests that unraveling the shadow gun economy requires focusing on the formal institutions and processes of the State rather than the covert operations of gun-running syndicates in conflict-affected Mindanao and its porous borders. It lends new meaning to the African conflict scholar Francois Bayart’s notion of “criminalization of the State.”

This is the reality that stares us in the face and puts recent gun-related violence and the proposed policy reforms being debated in their proper context.

Decommissioning

Anticrime groups and ban-the-gun advocates may be better served by focusing on the decommissioning of weapons. The recent decision to upgrade the guns used by the Philippine National Police to the standard 9mm Glock 17 Generation 4 pistols is a case in point. The PNP spokesperson called it the most transparent bidding process the PNP had conducted. Yet, an important issue lurks behind the procurement deal that is hidden from public scrutiny.

What happens to the tens of thousands of small arms and light weapons that will be replaced under the government plan? Will these weapons be destroyed, sold or transferred to other security forces?

The need for weapons disposal and decommissioning is masked by the effort to reduce the gun deal into an issue of transparency in government procurement. These weapons, both old and new, have serious implications for State building, security, crime and rebellion. Decommissioning these weapons ensures that they do not end up in grey markets.

Regulatory weakness

The problem of illicit weapons is also reinforced by various regulatory weaknesses. Guns captured from criminal gangs and rebel weapons retrieved from the battlefield are not properly inventoried. Repeated gun amnesties produce new numbers in gun ownership without accounting for those weapons licensed earlier that are not re-registered. Memorandum receipts and mission orders mask the use of illicit weapons in anticrime and antiterrorist operations.

The harnessing of paramilitary groups as “force-extenders” and the easy licensing of security agencies allow the de facto legalization of illicit guns and the subcontracting of coercive force and violence to unaccountable groups.

Loose stockpiling

The regular transfers of guns between various police and military units, and the loose stockpiling of licit and illicit weapons open the door for further malfeasance. It also underscores the porous nature of the firearms market. Interviews with regulators demonstrate the licit and illicit terrain that they navigate on a daily basis—as regulators on the one hand and “fixers” on the other.

Indeed, the systematic leakage from formal to informal and licit to illicit markets and vice versa, is the rule rather than the exception in the local gun economy. One of the many examples is illegal-to-legal gun ownership of the perpetrator of the recent Cavite killings: two high-powered rifles and a Sig Sauer cal. 45 pistol that were formerly illegal but legitimized through an amnesty by the previous administration.

These issues should be urgently addressed because curbing the spread of illicit weapons is not only a deterrent against crime but a key factor in consolidating the government’s coercive powers. It is crucial in crippling the legitimacy and authority of local warlords and thugs who provide more protection than the State is able to give. It will also determine the success or failure of peace talks with the MILF and the National Democratic Front.

Institutional reforms

In the face of numerous policy proposals following the recent tragic violence, Sen. Francis Escudero, chair of the Senate justice committee, argued for the need to develop a more effective legislation to improve previous gun laws that are at least 25 years old. “Calling for tougher sanctions against gun violators will not work unless the law and the means to enforce it are radically improved and strictly implemented,” he said.

This article takes a leaf from this critical suggestion.

The first law regulating firearms possession, importation, acquisition and transfer was enacted by the American legislature in 1907. President Ferdinand Marcos issued Presidential Decree No. 1866 in 1983 to codify all laws pertaining to firearms, explosives and ammunition.

Congress enacted Republic Act No. 8294 in June 1997, known as the Firearms Law of the Philippines amending PD 1866. This law places limits only on the caliber of the gun and penalizes violators who do not license their firearms and who carry them outside their homes.

Violators are imprisoned for one to five years and suffer a fine for the illegal manufacture, sale, acquisition, disposition or possession of low-caliber handguns.

A short detention period of 1 to 30 days is imposed on persons found in possession of licensed firearms outside their residence without legal authority. These provisions are clearly in need of radical change.

Physical threat

Ordinary citizens face a genuine physical threat from the absence of any credible and transparent program for collecting loose firearms and in disposing of tens of thousands of firearms in storage or set to be replaced. It is bound to worsen the impact of the shadow market in guns on the security of citizens and to pose a very real threat to security and political stability in the run-up to the 2013 elections.

Thus, the re-registration of all legal firearms should be immediately undertaken by the PNP-Firearms and Explosives Office with adequate oversight by the Department of the Interior and Local Government, and the Department of Justice to determine actual ownership, update ballistic records and ring fence all the legal from the illegal weapons in the possession of civilians.

(Ed Quitoriano is the author of an Ausaid-funded study of the illicit arms market in the Philippines, titled “Out of the Shadows: Violent Conflict and the Real Economy of Mindanao.” He works as an independent risk and conflict analyst for several development agencies.)

Distribution of guns in PH

Place Total % Licensed % Unlicensed %

Luzon 2,060,000 73 675,269 73 1,390,000 73

Visayas 270,000 9.5 119,747 13 148,900 8

Mindanao 490,000 17.5 134,018 14 358,250 19

Total 2,830,000 100 929,034 100 1,905,679 100

Sources: AFP-J2, PNP-FEO (2010 and 2011), BagayaUa (2011)

Loose firearms in PH

Place Number Percent

Metro Manila 1,100,000 58

Rest of Luzon 290,000 15

Visayas 148,900 8

Mindanao 358,250 19

Total 1,905,679 100

Sources: AFP-J2, PNP-FEO (2010 and 2011), BagayaUa (2011)