What are sign languages?

Common misconceptions:

Signing is universal.

Signing is gesture or only pantomime.

Sign languages are based on spoken languages.

Sign languages have been demonstrated to be true languages at par with spoken languages. Spoken languages are based on classes of sound, while sign languages are built from visual units. There are over a hundred sign languages currently recognized around the world.

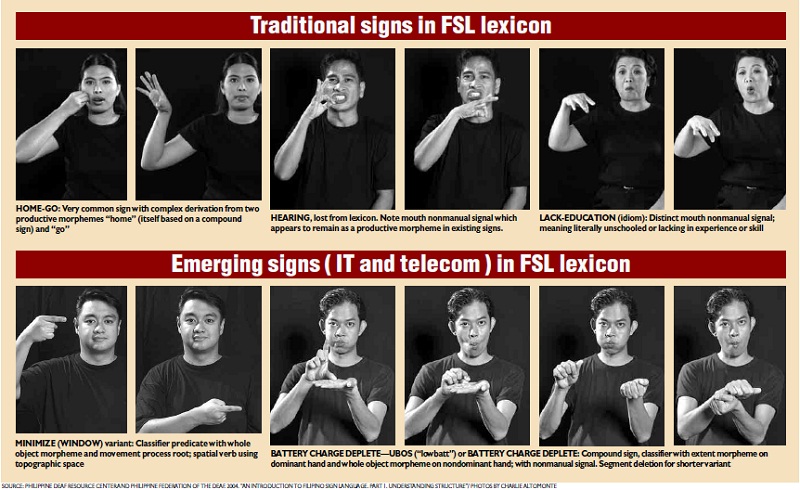

The fundamental unit of structure is the Handshape, along with the other parameters of Location, Movement, Palm Orientation and Nonmanual signal. These are further organized into units which carry meaning, and then, sentences and discourse.

Sign languages have no written systems and are governed by purely visually motivated grammatical devices found in the Nonmanual signals of the face and body.

How do sign languages differ from sign systems?

Sign languages arise and grow naturally across time, within communities of persons with hearing loss. A sign language is not intrinsic to children with hearing loss but is among the set of learned behaviors within the community that is shared, nurtured and passed on.

Sign languages possess their own structure distinct from spoken and written languages.

Sign systems, on the other hand, are considered artificial since they did not arise spontaneously but were purposively created as educational tools in the development of literacy. Artificial sign systems follow the structure and grammar of spoken and written languages.

What is Filipino Sign Language (FSL)?

Common misconceptions about Filipino Sign Language:

It is based on Filipino.

It is based on English.

It is the “same” as American Sign Language.

Like other legitimate visual languages, FSL has a hierarchy of linguistic structure based on a manual signal supplemented by additional linguistic information from Nonmanual signals of the face and body. It is the ordered and rule-governed visual communication which has arisen naturally and embodies the cultural identity of the Filipino community of signers.

It shows internal structure distinct from spoken and written languages, and other visual languages, and possesses productive processes, enabling it to respond to numerous current and emerging communication needs.

It reflects rich regional diversity in its vocabulary and bears a historical imprint of language change over time since the early beginnings of manual communication in the 16th century in Leyte.

From the lexicostatistical analysis of field data by the Philippine Federation of the Deaf (PFD), possible varieties have so far been proposed: an Eastern Visayas group (Leyte variety) and a Southern Luzon group (Southern Tagalog, Bicol and Palawan varieties).

FSL bears the historical imprint of heavy language pressure from contact with American Sign Language since the start of the century, as well as with Manually Coded English since the 1970s.

In 2004, sign linguist Liza Martinez called attention to the massive and abrupt change of the core vocabulary of FSL, which has resulted from this linguistic pressure. The PFD historical analysis in 2007 used the lexicostatistical approach and verified vocabulary elements of indigenous as well as foreign origin.

Distinguished sign linguist James Woodward has been at the forefront of pioneering research to protect endangered indigenous sign languages (including FSL) and stem the strong tide of influence from foreign sign languages and sign systems.

Who are the Filipino deaf?

These are Filipinos who have hearing loss, including those who lost their hearing early or late in life (late-deafened adults, senior citizens), the hard of hearing, those with other impairments such as the deafblind, those who communicate orally, unschooled deaf, LGBT deaf, deaf indigenous peoples and so on.

Who are the Filipino Deaf?

They are deaf Filipinos who use, share, nurture and promote common values (including their visual language and cultural identity) as a claim for human rights and self-determination.

How are FSL and American Sign Language related?

FSL belongs to the branch of visual languages influenced by American Sign Language together with, for example, Thai Sign Language and Kenyan Sign Language. However, the structure of FSL has changed significantly enough for it to be considered a distinct language from American Sign Language.

There is substantial evidence of widespread FSL changes in the following:

Overall form, internal structure (particularly on the inventory of handshapes and accompanying phonological processes)

Sign formation or morphological processes (such as affixation, compounding, numeral incorporation, lexicalization of finger spelling, inflections and others)

Classifier predication, grammatical features and transformational rules, enabling it to generate infinite forms of surface structure from patterns of deep structure

What is the legal basis for House Bill No. 6079?

The bill is known as “An Act Declaring Filipino Sign Language as the National Sign Language of the Filipino Deaf and the Official Language of Government in All Transactions Involving the Deaf, and Mandating Its Use in Schools, Broadcast Media and Workplaces.”

The State is duty-bound internationally and domestically to legislate HB 6079 or other laws written in the same spirit. International commitments include its ratification of UN core treaties, e.g. the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD) and the Convention on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, as well as the signing by the Philippines of the 1994 Salamanca Statement on Special Needs Education.

Department of Education (DepEd) policies include the 1997 specific guidelines on the use of FSL as the medium of instruction for students with hearing impairment. Recent or proposed DepEd policies, such as those for Mother Tongue-based Multilingual Education, the K-12 bill and the Early Years Act, already incorporate principles of full accessibility, inclusion and participation of children with disabilities.

Is this legal recognition of a national sign language taking place only in the Philippines?

No. Forty-four countries are reported to have various levels of formal recognition for their sign languages, from constitutional status to specific legislation, polices or guidelines.

Sign language recognition continues to be an area of active lobbying with the government for Deaf communities worldwide, which invoke their right to language and communication in all aspects of their lives.

How much research has been done on FSL?

Rosalinda Macaraig Ricasa, the first Filipino hearing sign-language linguist who trained at the renowned Deaf institution, Gallaudet University (Washington), first presented in the late 1980s the observation of a possibly unique sign language in the Philippines, distinct from American Sign Language.

In 1990, Liza Martinez, the second Filipino hearing sign-language linguist who trained at the same Deaf university, conducted the first linguistic inquiry in the country. Since that time, over 80 studies on the structure and use of FSL have been undertaken and published or presented in local and international forums.

These span the fields of sign language linguistics, history, Philippine studies, literature and culture, lexicography and corpus, sign language interpreting, translation studies, language policy, education, early childhood development, human rights and machine intelligence/sign language recognition.

The Philippine Federation of the Deaf was the lead for the National Sign Language Committee, which produced the Status Report on the Use of Sign Language in the Philippines (with principal support from the Gallaudet University Alumni Association through the Laurent Clerc Cultural Fund) and the Practical Dictionaries Project, a four-country study with Vietnam, Cambodia and Hong Kong through the support of Nippon Foundation.

Trainers for the latter project were Dr. James Woodward,

Dr. Yutaka Osugi (a Deaf sign linguist from Japan) and

Dr. Liza Martinez.

How are deaf children taught in public schools?

The National Sign Language Committee collected and evaluated videotape samples of over 150 hearing teachers in nine regions. The data show typically Sign Supported Speech or Simultaneous Communication (i.e., speaking and signing at the same time). The most frequent use of the spoken language is English, mixed with either Filipino or Cebuano.

Will HB 6079 hinder the development of literacy?

No. Section 4 (1) of the bill states that the reading and writing of Filipino, other Philippine languages and English shall still also be taught. For a bilingual-bicultual goal in Deaf education, the first language (L1) is a fully accessible visual language (i.e., FSL), and the second language (L2) is a written language.

Shall the legal recognition of FSL as the national sign language conflict with individual autonomy?

No. A fundamental principle of the UNCRPD is individual autonomy, including the freedom to make one’s own choices (Article 3.a).

On education, Article 24.3 emphasizes that “States Parties shall enable persons with disabilities to learn life and social development skills to facilitate their full and equal participation in education and as members of the community. To this end, States Parties shall take appropriate measures, including:

(b) Facilitating the learning of sign language and the promotion of the linguistic identity of the deaf community;

(c) Ensuring that the education of persons, and in particular children, who are blind, deaf or deafblind, is delivered in the most appropriate languages and modes and means of communication for the individual, and in environments which maximize academic and social development.”

Part (b) is a clear directive to facilitate and promote the linguistic identity of the community (i.e., FSL). Notable is the use of the word “including” in the first paragraph (meaning, it is not exclusive) for the directive to promote this linguistic identity.

Part (c) instructs the State to make sure that schools, in pursuit of their goals and mandates, offer education that is appropriate and maximizes academic and social development. This appears to give schools latitude in the choice and delivery through the use of various languages, modes and means. However, these must satisfy the requirements for fully inclusive education and maximum development.

Article 21.b directs the State to guard the freedom of expression and access to information of persons with disabilities of all forms of communication “of their choice,” while also recognizing and promoting the use of sign languages (21.e).

The most critical point here is State responsibility. The party to the convention is the Philippine state and not any stakeholder. The State must, therefore, clearly demonstrate that it is carrying out its duty to facilitate and promote the linguistic and cultural identity of the community (Articles 21.b, e; 24.3.b, 30.4) and provide full accessibility through sign language interpretation (Article 9.2.e). Articles 21.b and 24.3.c in no way diminish State commitment to clearly promote and protect sign language and deaf culture.

What will happen if HB 6079 does not become a law?

State responsibility remains clear and does not change. It shall still need to demonstrate how it is implementing Articles 21.b, e, 24.3.b, 30.4 and 9.2.e of the UNCRPD. It shall also be accountable for the nearly two decades of neglect of its commitment to the 1994 Salamanca Statement to ensure access through a national sign language.

Existing policies of the DepEd and the judiciary relating to sign language and accessibility must still be fully implemented according to the principles and obligations of the UNCRPD.

Will the mandatory use of FSL be a barrier to unschooled deaf Filipinos?

No. Because of its fully visual nature, FSL is the next most efficient and effective interface in communication even with a deaf person who has been isolated and is unable to use the typical sign communication of the community. Artificial sign systems, which are sound- and alphabet-/spelling-based, shall be incomprehensible to such deaf persons.

(Dr. Liza Martinez is founder and director of the Philippine Deaf Resource Center, a member of the Philippine Coalition on the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. She has been actively involved in structural and sociolinguistics research on FSL for the past 22 years.)