Trained for torture

But alas, the people are supporting the AFP, providing the money for its expensive wars that seem to have no end in sight and thus, no end at all for people’s sacrifice.

The AFP has defended the torture as a form of training recruits. So are people supposed to support this rather unorthodox form of training with their money, too? Moreover, does that mean that torture and physical abuse are institutionalized in the military? If so, why should the people pay for measures that, based on gruesome human rights cases, have been used against the people?

Article continues after this advertisementAnd what about the pledge of the military to respect human rights? How can an institution that makes torture and abuse part and parcel of its training make human rights its paramount concern?

The persistence of torture and instruments of violence in the work of people tasked to enforce the peace dates back to the Cold War, where mayhem and murder were supposed to be carried out in a war that was low-key and low-intensity, which means they should be carried out surreptitiously, clandestinely, but a war that was nonetheless brutal and ideologically twisted, and sadly enough, a war turned against non-combatants and the citizens themselves.

Completely confusing the enemy, the military and the police have made war on the people they have sworn to protect. In the context of the Philippines, where the ideological wars remain because of the persistence of conflicts and insurgencies, torture represents a persistence of past practices, a throwback to an era whose tentacles continue to smother and constrict any attempt to foster a more humane society, one that is grounded on the ways of peace and civilization.

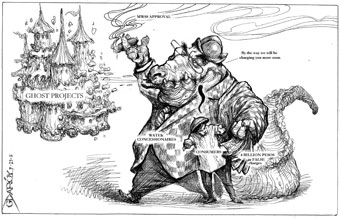

Article continues after this advertisementThe resilience of torture and terror tactics has perpetuated the insurgency and other conflicts. Because neither the government nor the insurgents can win the war decisively, they resort to foul, underhanded techniques to get back at or put one over each other. It is a matter of record that the military and the insurgencies have fed on each other’s blood lust. In fact, both seem to thrive on each other’s underhandedness, thus prolonging the war that neither wants to win because that would mean the end of their reason for being. This explains why our insurgencies continue to fester, and Filipinos now live under constant siege. We are a nation in a perennial state of war. The Philippines has become a nation of checkpoints. Even malls and schools have spot security checks.

For the police, the ready recourse to terror tactics to extract confession and intelligence information against the enemy has only fostered incompetence, professional laxity, and consequently intractable criminality. Several celebrated cases of heinous crimes have remained unsolved due to the botched handling by the police who resorted to shortcuts to yield results for publicity. Trained in the ways of terror to obscure shoddy police work, our law enforcers meld with the faces of the criminals they pursue. They become the criminals themselves, underworld characters in state uniform.

It is shocking that tactics and strategies associated with totalitarian despots, which have riled and roused peace-loving people around the world and unleashed the pro-democracy wave that is sweeping Tunisia, Egypt and the rest of the Arab world, are proving to have a long shelf life in the Philippines. The country, ironically enough, started the international people power movement a generation ago. The Arab phenomenon is a credit to the power of the People Power Revolt of 1986. It is regrettable that on the 25th anniversary of the Edsa miracle, Filipinos are not celebrating the historic milestone in a manner that gives it credit and substance. Worse, we have chosen to return to the earlier era of abuse and strong-arm tactics. We continue to spurn the legacy of Edsa.