Beyond structures of Moro autonomy

A GIRL carries the flag of the Basques, a people who live in northern Spain and the southwestern part of France. A Basque group called ETA has waged an armed separatist movement in Spain. islandbreath.blogspot.com

MEMBERS of the Philippine government and Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) peace negotiating panels recently went to Navarra, Spain, “for a weeklong study of autonomy.”

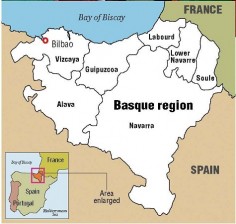

The trip was billed as part of the “preparations for the drafting of the annexes to the Framework Agreement on the Bangsamoro” signed on Oct. 15. In particular, the government negotiators were to study the Communidad Foral de Navarra (Regional Community of Navarra), “the northern Spanish autonomous community,” which runs on a “high degree of self-government but operate[s] within Spain’s structure as a nation of autonomous communities.”

ETA

The Navarra experience in self-governance will certainly provide valuable inputs into the Mindanao peace process. It is part of the Basque region, which gave birth to the armed separatist movement, the Euskadi Ta Askatasuna (Euskadi and Freedom, or ETA). This is thus an experience that the Philippines can find resonance with given the decades-long Moro insurgency in Mindanao, as waged by the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF) and the MILF.

While it is pertinent to study the structures of autonomy in Navarra, it is equally important to delve into the political and socioeconomic factors from which these have evolved and contributed to their effectiveness in the Basque region. There is thus a need to contextualize the structures of autonomy within the nature of Basque society in particular and Spanish society in general in order to understand why they have been successful and what challenges confront the Philippine case.

Industrialized areas

The region is currently one of Spain’s wealthiest and most industrialized areas. It is also said to have the highest degree of self-rule in all of Europe. This seems to be in stark contrast with the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (ARMM), which is among the poorest regions in the Philippines and whose experiment in autonomy has been deemed a failure by no less than President Aquino.

Colonialism

The sad fate of Muslim Mindanao could be blamed on the second factor which is the adverse impact of colonialism, an experience the Basque region does not share. P.N. Abinales in “Making Mindanao: Cotabato and Davao in the Formation of the Philippine State,” says that because Muslim society had a feudal structure, i.e., the sultanate, the strategy of colonialism pursued by the Americans was “to deal with the Muslim elites/royalty, i.e., the datus.

The end of American colonial rule brought Muslim Mindanao under “direct Filipino control” and the Muslim elites who accepted Filipino hegemony were subjected to the insidious and still currently prevalent practice of patronage politics. Abinales further notes that opportunistic Manila-based politicians also saw Muslim voting blocs as potential electoral support for their political parties.

The Basques, on the other hand, were not colonized and their political life was never dominated by their own national government, i.e., except under the Franco dictatorship. Moreover, their society is represented by class divisions. An example is the division between the urban industrial class and the rural class, as seen in liberal democratic societies.

Although there was a period when the Basque upper class associated closely with the Spanish oligarchy, the rest of society asserted its independence from this relationship. Thus, patronage politics did not develop and the Spanish central government never co-opted the Basque elite class.

Again, the level of economic development played a key role here. In Mindanao, the nonelite Moros could not assert themselves as they lacked not only the political but also the economic resources to do so, unlike their Basque middle class counterparts.

A third factor is that, unlike the Moro people, the Basques were not victims of economic marginalization. The Basque region is the country’s major producer of steel and coal and, together with Catalonia, has long been the historic seat of Spanish industrial and financial capital.

‘Imperial Manila’

As for Mindanao, the exploitation of its abundant natural resources did not benefit the Muslims and other local communities. Earnings from the resources were siphoned off to “imperial Manila.” In the Basque experience the migrants to the region never got to control the economy and they generally worked for the Basques.

A fourth factor was that Basque nationalism could not be curtailed despite the Spanish government’s attempt at federalism. The region suffered from cultural and political estrangement rather than economic exploitation. The former refers to the imposition of the dominant Madrid-based Castilian culture while the latter refers to the central government’s move against the fueros, “the single most important symbol of their political identity … which embodies local laws and privileges” and affirm an ancient political system.

With the advent of Spanish liberalism, the central government sought to abolish the fueros but without success. In the case of Mindanao, as Abinales noted, Islam was perceived to be a tool “to get more concessions through participation in the center’s politics.” Thus, the Moros were absorbed into a political system not of their making and worse, the Moro elite could “not use their positions as stepping stones for advancement through the state hierarchy.” This reality continues to exist in Philippine politics.

Indigenous bourgeoisie

A fifth factor is that the Basques spearheaded their own middle class-led economic development and bred their own indigenous bourgeoisie unlike in the case of the Moro Province, which was subjected by the development policies of the colonial ruler and later on, by the central government. The fact is, the Philippine state is weak and could not promote sustained economic development and its feeble attempts to do so were hamstrung by alliances with local politicians.

In the Basque experience, the region developed on its own with minimum intervention from the central government. Moreover, the beneficiaries of Mindanao’s development were mainly the elites from both the Muslim and the non-Muslim populations, whereas in the Basque region, members of the urban middle class were its major recipients.

A sixth factor was although Basque and Moro nationalism under the Franco and Marcos dictatorships intensified with the emergence of the ETA and the strengthening of the MNLF, respectively, Marcos sought to undermine the latter by cultivating ties with Moro elite families, thus giving rise to new Moro political dynasties. Generalissimo Franco, on the other hand, did not or could not cultivate any ties with the Basque elites.

Moro political kingpins

In the Philippines, the habit of perpetuating political dynasties to support the interests of particular national politicians continues unabated. Thus, during elections, Moro political kingpins determine electoral outcomes by delivering the needed votes from their respective “fiefdoms” for their national allies. A consequence of this is widespread electoral violence as epitomized by the horrific 2009 “Maguindanao massacre.”

Moreover, to this day, rido or clan wars continue to be a source of political and socioeconomic instability in Muslim Mindanao. These clan wars are exacerbated by the main Muslim ethnic differences among the Maguindanaos, the Maranaos and the Tausugs. This is unlike the Basques who all share a common ethnic identity.

A seventh factor is that the rest of Spanish society could sympathize with the Basque aspiration for self-determination vis-à-vis the central state. This sentiment is shared by several autonomous regions in Spain, e.g., Catalonia and Andalucia. But in the case of Muslim Mindanao, its struggles have been met with indifference and even hostility from the general Filipino public, particularly from non-Muslim communities in adjacent Mindanao regions.

An eighth factor is that the Basque question was dealt with internally. No external force aided the Basques in their struggle with the exception of France, which previously provided political refuge (but not military assistance) for Basque exiles. French support, however, has been withdrawn, a move later reinforced by the European Union’s declaration of the ETA as “terrorists” in the midst of the so-called “war on terror.”

External players

In the case of the Moro insurgency, external players, mainly from Islamic states, extended military, economic and political assistance to the rebellion throughout all its phases. This is understandable as electoral politics is still not an option for the Moros given the continuing co-optation of Moro elites. Leaders emerging from electoral contests have always represented political dynasties that are generally the national administration’s close allies.

External support in Muslim Mindanao is also seen through official development assistance from the World Bank, the United States, the European Union and Japan, among other groups. This situation is absent in the rich and prosperous Basque region.

Ideological bias

And ninth and last, the Basque peace process has been affected by the ideological bias of the Spanish national party in power that basically determines whether negotiations will be pursued with the ETA. If it is the Popular Party, the chances for negotiations will be dim but if it is the Socialist Party, chances are negotiations will be prioritized.

The issue of peace negotiations even becomes a factor when voters take to the polls. In the Moro situation, peace negotiations do not constitute an election issue. Thus, the pursuit of peace is determined arbitrarily by the personality of the leadership rather than the ideology of the political party to which the leader belongs. This can be traced to the nonideological nature of Philippine political parties, which are based on personalities or rooted in family dynasties.

The Basque experience provides the Philippines with comparative lessons on what factors made its regional autonomy a “success.” The all-important lesson here, therefore, is that although the institutional framework is certainly a relevant and crucial determinant in providing the guidelines for a functioning autonomy, it is equally essential that support be extended for structural changes not only in the autonomous region of Mindanao but also in the rest of the country.

(Teresa S. Encarnacion Tadem, Ph.D. is professor of political science, College of Social Sciences and Philosophy, University of the Philippines, Diliman. This article is excerpted from the author’s “Rise of Basque and Moro Nationalism: From Incipience to Dictatorship,” Philippine Social Sciences Review, Vol. 60-61 Nos. 1-2, January 2008-December 2009, pp. 95-124 [https://journals. upd.edu.ph/index.php/pssr/article/view/1278] and “Electoral Politics and Confronting the Challenge of Basque and Moro Nationalism,” Social Science Diliman, December 2010, Vol. 6, No. 2, pp. 50-78.)