A nuclear safety agency official told reporters: “Around 10:40 a.m. [9:40 a.m., Manila time] we ordered the evacuation of workers … due to the rise in [radioactivity] data around the gate” of Reactor 3.

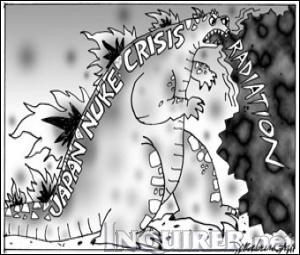

The pullout was only temporary, and the workers returned within the day. Unfortunately, the “containment vessel” in that same reactor appeared to have ruptured later in the day, releasing radioactive steam into the atmosphere. It was the second reactor in the Fukushima plant to release radioactive material in two days.

The turn for the worse, and especially the live video coverage of the crisis at the nuclear power plant, which showed clouds of white steam escaping from ruined buildings, deepened the anxiety of shell-shocked Japanese coping with the terrifying aftermath of the country’s worst disaster since 1945. The estimated death toll from the tsunami generated by Friday’s magnitude 9 earthquake has now topped 11,000.

To be sure, the immediate threat to the rest of the world is practically nil. “The odds of someone outside the plant getting an acute injury—sick in the next couple of weeks—is close to zero,” John Moulder, an American professor of radiation oncology, told the Associated Press.

Part of the reason is that the radiation leaks likely carry cesium and iodine, radioactive particles that, as Steven Reese, director of the Radiation Center at Oregon State, told AP, can combine with the salt in sea water to become sodium iodide and cesium chloride, common elements which can easily dissipate over the Pacific Ocean.

But Japan’s neighbors are not resting easy. Russia has history to blame; the worst nuclear power plant disaster took place in Chernobyl, in 1986, and the way the government mishandled the crisis sowed distrust that lingers 25 years on. “The mass media tell us that the wind is blowing the other way, that radiation poses no threat. But people are a mess,” AP quoted a Vladivostok citizen’s comment, posted on a newspaper website. “They don’t believe that if something happens we’ll be warned.”

The Philippines has history to blame, too, but it is only a history of overreaction. In the same way that the first Persian Gulf war in 1991 led anxious Filipinos, thousands of miles away from any possible danger, to empty grocery shelves, anxious Filipinos have been passing improbable rumors about radiation from Japan reaching Philippine shores. Only this time, the misinformation multiplied at the speed of SMS.

Some text messages contained suggested remedies to use in case of radiation, such as the popular Betadine. Some purported to quote news organizations, such as the BBC. Some even pinpointed the time the first wave of radiation would arrive: 4 p.m.

On the face of it, these messages should have been ignored by Filipinos who have been following the news, in the papers, on TV, or online. The developments in the Fukushima plant have been followed closely and reported accurately. Tragically, even the president of a state university, apparently deciding that ignorance was the better part of valor, called classes off last Tuesday—an act that, spread by SMS again, only seemed to confirm the rumors.

The emergency at the Fukushima complex may still turn out to be even worse than Chernobyl, but at the moment that outcome looks highly unlikely. Simply put, more safeguards were in place in Fukushima. As Agence France Presse reported: “The head of the UN’s atomic watchdog said that unlike Chernobyl, the Fukushima reactors have primary containment vessels and had also shut down automatically when the earthquake hit, so there was no chain reaction going on.”

A serious risk does exist, however. The lives of the crew members at the facility, and residents within a 20-kilometer radius of the plant, are vulnerable to exposure to the radioactive releases. In other words, the crisis is for real—but not in the way irresponsible text messages depicted it.