The 2000s: lost decade or best decade?

Appointed only two months ago by President Aquino as the chief of the National Economic and Development Authority, former UP School of Economics dean Arsenio Balisacan seems to have fast caught the yellow I-hate-Arroyo bug that afflicts this administration.

In a speech last week, Balisacan even mimicked the Aquino propagandists’ crass tack of using clichés in the asinine belief that catchy terms can substitute for facts and reason. Balisacan labeled former President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo’s years from 2001 to 2010 as a “lost decade,” because, he claimed, poverty was not reduced during the period. “You know what happened in the last decade? Walang nangyari sa poverty talaga, flat lang,” he said.

I won’t present any data or argument to refute Balisacan’s claim, but just repeat what he himself wrote, together with four other economists, in a report for the Asian Development Bank in 2010 titled “Social Impact of the Global Financial Crisis in the Philippines.” That he didn’t think he made mistakes in his conclusions there is reflected in the fact that he later wrote shorter versions of the study in various academic journals.

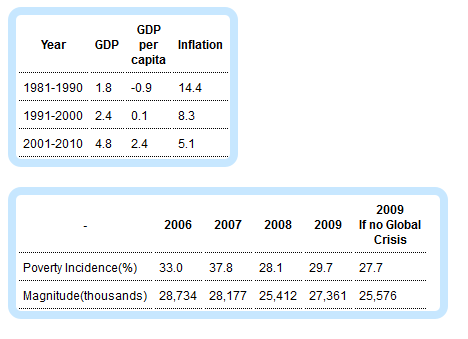

The Balisacan report was all praise for the reduction of poverty during Arroyo’s term: “[Poverty] significantly decreased from 33 percent in 2006 to 29.7 percent in 2009. The growth of household incomes in 2007 and 2008 has favored the poor as their incomes have increased proportionately more than those of the richer households.”

It even emphasized: “The decline of poverty in the rural areas is remarkable. It was decreasing at an annual rate of 3.7 percentage points between 2006 and 2008.”

While Balisacan claimed in his speech last week that there was no poverty reduction during Arroyo’s watch, his own study reported that it declined from 33 percent in 2006 to 29.7 percent in 2009 (see table below, directly lifted from the study).

But not only that, the Balisacan study’s important insight is that it was the global financial crisis that broke out in 2008, and was at its worst the next year, which was the main reason for the worsening in poverty from 2008 to 2009, to a 29.7-percent incidence. Because of this, the very wrong impression—which afflicted even the author of the study when he was appointed Neda chief—is that “nothing happened in reducing poverty” during Arroyo’s term.

Using rigorous econometric models, the Balisacan study concluded that if not for the global financial crisis—considered worse than the Great Depression of the 1930s—the poverty incidence in 2009 would have been 27.7 percent and not 29.7 percent, or a huge two percentage points lower. Without the global economic crisis, there would not have been a 2-million increase in poor Filipinos.

The Balisacan study in fact extolled the Arroyo administration’s moves that enabled the country to still post a 1.1-percent GDP growth, when most countries went into recession. It noted that the Arroyo administration had a comprehensive response to the emerging global crisis, contained in the so-called “Economic Resiliency Plan” (ERP) which the then President ordered the Neda (then headed by Ralph Recto) to formulate and execute when the global crisis started to emerge in 2008.

The Balisacan study also explained: “With a total budget of P330 billion or an estimated 4 percent of GDP, the ERP aimed to stimulate the economy through tax cuts, increased government spending, and public-private sector projects.” The increase in public infrastructure projects substantially boosted the GDP, since private economic activity—especially in exports, as the US market contracted—had slowed down.”

According to Balisacan’s calculations, because of the country’s economic fundamentals, the GDP growth rate in 2008—if the global crisis did not occur—wouldn’t have been just 4.2 percent but 5.2 percent, and in 2009, not 1.1 percent but 4.9 percent. Because of the economy’s strengthening during Arroyo’s watch (through such policies as the very unpopular expanded value-added tax law) and because of her appropriate response to the crisis, the economy bounced back immediately after the global financial storm with a remarkable 7.6-percent growth in 2010. This has made possible such things that you will hear Mr. Aquino crow over on Monday as international credit-rating upgrades, low inflation rates, and robust government coffers.

Even with the lower GDP growth because of the global crisis, the annual average GDP growth during Balisacan’s “lost decade” is 4.8 percent, much higher than those in the past two decades (see table below, based on World Bank data). In fact, the last decade had the highest annual growth in GDP per capita and the lowest inflation rate—two crucial economic measures that determine poverty incidence.

What “lost decade” is Mr. Aquino’s top economist talking about? Just go by the hard data: It was the best decade.

E-mail: tiglao.inquirer@gmail.com