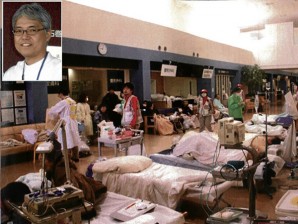

INSET: Dr. Tadashi Ishii. The large entrance hall of the Ishinomaki Red Cross Hospital is turned into a temporary treatment area.

ISHINOMAKI, Japan—Foresight paid off big for a Red Cross hospital here, whose experiences in the aftermath of the earthquake and tsunami in 2011 can offer the world valuable lessons in disaster response.

Knowing when to set aside hierarchy and “face,” practicing selflessness and embracing improvisation also enabled doctors and other care providers to “pull together as one” in delivering services to disaster victims, said Dr. Tadashi Ishii.

Ishii is the Miyagi Prefecture disaster medical coordinator at the Ishinomaki Red Cross Hospital.

The hospital, founded in 1926 as the Miyagi branch hospital of the Japanese Red Cross Society, was moved 4.5 kilometers from the coast and rebuilt as a quake-resistant structure in 2006.

The payoff came when a 9-magnitude earthquake struck northeast Japan off the coast of Ishinomaki.

Beyond tsunami’s reach

The 402-bed medical facility emerged from the temblor undamaged and its location kept it beyond the reach of the devastating tsunami, said Ishii.

As a result, the Red Cross hospital became the only core medical facility for survivors, as most of the 140 medical facilities in the city and nearby areas were rendered nonfunctional by the disaster.

Immediately after the Great East Japan Earthquake struck at 2:46 p.m., a Level 3 disaster condition was declared, Ishii said.

Triage

At 3:43 p.m., the hospital completed the triage area and began treating disaster victims.

Its large entrance hall, which has oxygen outlets, became a temporary treatment area.

On Day 1, only 99 people reached the hospital, as 12 of the 17 ambulances in the city were lost to the tsunami.

“If the information reached the government immediately, other transport options could have been considered” like helicopters from the Japan Self-Defense Forces (JSDF), Ishii said.

He said the transport woes came about partly because of the risks that go with relying too much on Net-based communication. Most information flowed one way and the absence of a request for help did not always mean that help was not needed, the disaster medical coordinator said.

Lack of awareness due to the absence of information was “merely an excuse” not to act, he added.

Temporary pharmacy

The immediate challenge that the Red Cross hospital faced was the disabled medical facilities and pharmacies in the Ishinomaki zone, which led to the hospital being inundated with prescription needs.

There was not enough staff to examine patients and to issue prescriptions, according to Ishii. Space was also a problem for a temporary pharmacy inside the hospital.

His team’s response was to set up a dedicated prescription booth inside the hospital and a tent pharmacy just outside the building.

The work of the medical staff was not confined to the hospital. “Where a hospital was destroyed and medical staff killed, we put up aid stations,” Ishii said.

Doctors killed

Doctors and other medical practitioners were among the 3,274 people killed in Ishinomaki, a city of some 162,000 residents before the disaster. (One of the fatalities was a Filipino woman married to a Japanese.) Missing were 706 people who were believed to have been carried off to sea by the retreating waters.

As one of the facilities undamaged by the disaster, the Red Cross hospital also conducted relief operations.

It extended its services to emergency shelters across the disaster zone in response to the JSDF appeal for relief teams to begin work on March 12 on a best-effort basis.

But the Red Cross had no basic information on the availability of water and provisions, power and water supply, sanitary conditions and heating in the shelters.

Neither did it have information on the injured and the sick, whether they were suffering from fever, external injuries, gastrointestinal illness or cough.

Isolated

“Administrative functions were paralyzed and could not be relied on to respond to inquiries,” Ishii said. In addition, communications were unreliable as the region was almost completely isolated.

“Nevertheless, there was the large risk that inadequate response will lead to many additional fatalities.”

Ishii said the only alternative was to gather information directly and implement an “emergency shelter triage.”

The Red Cross started assessing the needs at the emergency shelters, completing the task on March 19 after three days.

Code of conduct

From the team’s experience, Ishii came up with a code of conduct for relief work:

Failure to seek means failure to gain (information, partners with whom to negotiate, etc.)

Victims are in need and therefore cannot be neglected

Be ready to do anything necessary, even beyond the realm of the medical.

“No improvement in the situation can be expected if you don’t confirm on your own and simply rely on others,” he said. “Critics are not needed.”

Ishii said that allowing for neglect meant risking an increase in the number of fatalities.

Satellite phones

Restoration of communications on March 16 helped the Red Cross in relief operations and in coordinating with disaster medical assistance teams (DMATs) and other groups. NTT Docomo set up a base in a nearby elevated area and provided two satellite phones and 20 “priority” mobile phones.

Even before NTT Docomo restored communications, the Red Cross and DMATs had sent 17 relief teams to emergency shelters on Day 2, 20 on Day 3 and 27 (including other groups) on Day 4. By Day 6, only Red Cross teams remained as the DMATs and other groups had withdrawn from the area.

Two hours’ sleep

Due to the demands of work, Ishii said he had only two hours’ sleep daily for one week after the March 11 disaster.

The hospital handled 3,938 emergency cases in the first week, 1,251 of them on the third day. (See chart.)

In the first few days, the Red Cross was faced with patients finding it difficult to relieve themselves, especially at night, because conventional portable toilets were placed outside the hospital where temperatures were freezing.

If the problem persisted, the patients’ fluid intake would decrease, making them vulnerable to deep vein thrombosis and cystitis, according to Ishii.

Wrap-type toilet

To address the problem, the hospital resorted to making use of a “wrap-type” toilet that can be placed indoors. The contraption, which looks like a chair with arm rests, has heat-sealed individual waste bags. This kind of toilet seat is usually for the JSDF and for exploration teams in the South Pole, according to Ishii.

The scale of the disaster made the hospital enlist the help of other medical groups and organizations. “As Miyagi Prefecture Disaster Medical Coordinator, I knew that enhancing efficiency required coordination with the many medical teams arriving from around Japan,” Ishii said.

On March 20, the Ishinomaki Joint Relief Team was launched under the unified command of the disaster medical coordinator appointed by the governor.

The umbrella group included medical and dental associations, the Tohoku University and Ishinomaki Municipal Hospital, prefectural hospital medical teams, Red Cross relief teams, psychiatric and pharmacist associations, JSDF medical teams and nonprofit medical organizations.

No foreign doctors

The joint relief team did not accept offers from foreign medical personnel for help. “No, thank you for someone who cannot speak Japanese,” Ishii said.

It was announced that the Ishinomaki Zone Joint Relief Team was not the Red Cross Relief Team. In line with this setup, Ishii and members of the relief team started wearing T-shirts.

The result was amazing. The number of participating teams as of March 26 had risen to 59, comprising 100 physicians, Ishii said.

In interpersonal relations with the various members from different medical teams, Ishii’s being the disaster medical coordinator for the prefecture gave him significant negotiating leverage.

He said one should be prepared to disagree frankly when needed, but an inflexible attitude was taboo. “If someone has a better idea, adopt it immediately; remedy one’s own mistakes quickly and move on.”

Line managers

The joint relief team introduced area or line managers to cope with the huge work.

Still, at shelters and aid stations, relief teams could not carry sufficient types and amounts of needed medicines. The teams adjusted and brought prescriptions to the Red Cross hospital where pharmacists filled out the prescriptions. Melon Bread and relief teams on five vehicles delivered the medicines.

The disaster also compelled the Joint Relief Team to come up with a revised concept of priorities, according to Ishii. For the acute stage, the focus was on life-saving efforts; for the emergency stage, it was health preservation; and for the chronic stage, it was to hand over cases to local medical care and to promote the revival of local care capacity.

Excessive medical relief, however, could backfire, according to Ishii. It was important “not to give people the impression that they were abandoned” but there should be a time to “fade out” by taking measures like allowing private practitioners to come in, providing people with transportation and rebuilding medical infrastructure.

During the first 100 days, the Joint Relief Team handled 18,381 emergency patients. It had treated a total of 53,696 patients at evacuation centers as of Sept. 9, 2011.

Ishii said participating medical experts determined daily policy, provided management expertise and operational support, advised on mid- and long-term outlook, and gave strategic advice.

Ishii said he was fortunate to be a graduate of Tohoku University, which extended the team backup support. The university sent a total of 221 physicians with 30 specializations between March 14 and April 15.

“We are convinced that reducing the load on IRCH as much as possible is the best way for us to contribute as a university hospital as our main objective,” Dr. Susumu Satomi, Tohoku U Hospital director wrote in an e-mail to Ishii on March 26. The university hospital accepted 198 transfer patients in March and April alone.

Browsing site, buses

The efforts of the team were aided by Google, which provided a dedicated shelter information site. The team also got free medical relief buses from Aeon, tents from Sekishu House, bag-type toilets from Nihon Safety and diagnostic equipment from Nihon Kohden.

Ishii said the disaster required basic mental preparedness. “Response plans are effective in rapid first response to the initial disaster impact,” but he said “each disaster presents a unique set of ongoing practical problems,” so that “total disaster planning is impossible.”

Too much planning, he said, could hamper response to unforeseen events.

Ishii said there was no time for extended deliberations. It’s not “what should be” or “who should do it,” but “what do we do?” and “how do we do it?” he said.

Preparedness

In short, he said disaster response was all about:

- Preparedness

- Willingness to stay the course

- Personal networks

- Consensus and compromise

Even before March 11, 2011, the Red Cross hospital was already primed to perform the work demanded of it in a disaster.

In 2007, Ishii was named director of the hospital’s medical social work. The following year, the hospital conducted a full-scale rehearsal (disaster response) and came up with a manual.

In 2009, it built a network through a Japanese Red Cross DMAT conference and the hospital director approved the dispatch of the Red Cross Disaster Relief Team.

In 2010, the Ishinomaki Regional Disaster Medical Representative Network Council was established and training with a disaster relief helicopter was conducted.

The Red Cross hospital also signed an agreement with NTT Docomo, Sekisui House and Shisuikai.

Ishii, a Christian, had wondered whether it was an accident or fate that thrust him and the Red Cross Hospital into the middle of the disaster response in the Ishinomaki zone.

“It was my fate,” concluded Ishii, a father of three, who goes home to his family in Sendai, the regional center, every two weeks.

(The writer was among the 10 journalists from Asia invited by the Japanese Foreign Ministry to Japan in October last year to look at the country’s recovery efforts.)

Great East Japan Earthquake

Main shock

Magnitude 9 on March 11 with epicenter 120 kilometers off the northeastern coast

Aftershocks

Magnitude 7 or greater, six times

Magnitude 6 or greater, 93 times

Magnitude 5 or greater, 559 times (as of Aug. 31)

Tsunami

40 meters, maximum height of waves in certain areas that devastated communities in 15 prefectures along a 700-km coastline

Casualties

15,824, dead

3,847, missing

5,942, injured

400,000, people displaced from affected areas, including the 30-km zone around the damaged Fukushima Daiichi nuclear reactors

114,464, houses completely destroyed

154,244, houses half destroyed

539,840, houses partially damaged

Sources: National Police Agency, Japanese Red Cross and Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry