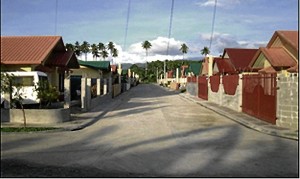

ORCHIDS Homes Subdivision in Santiago, Iligan City, before and after Tropical Storm “Sendong” (photo credit:www.firmbuilders.com.ph)

“Who would have thought a flood could bear so much force to bring my house down and wash it out to sea? I live in a middle-class subdivision in Santiago, Iligan City, called Orchid Homes and it is now leveled to the ground. The entire row of houses where my neighbors and family dwelled, crumpled against rampaging floodwaters and all that is left are bent steel and debris,” Edward Banawa said as he recounted his ordeal.

An associate professor in Iligan Institute of Technology of Mindanao State University, Banawa nonchalantly described his family’s misfortune on the tragic day of Dec. 16, 2011. Taken aback, I wondered about his composure. It became clear to me when I asked other victims of the massive flooding brought by Tropical Storm “Sendong.” There was consistency in their reactions, with everyone responding in a similar undisturbed tone. Perhaps they discovered an internal core of strength, their way to cope with shock and exhaustion. Maybe all their tears just dried up.

River watershed

Orchid Homes Subdivision is on a flat area near the mouth of Mandulog River, a waterway more than 50 kilometers long that serves as the main drain of the mountains of Iligan. This mountainous area covers about 70,000 hectares of land often referred to as a watershed in textbooks. Hundreds of smaller rivers connect to Mandulog River and form a network of channels similar to the branches of a tree. It is the main trunk where most of the storm water collected by the mountain watershed passes through before reaching the sea.

Flat areas beside large rivers are called floodplains. They are called such for good reason. During periods of heavy rainfall, the river channels swell and form overbank flow that encroach on adjacent fields. Floodwaters that inundate the area beside the river are laden with sediments. When the floods recede, mud and sand are left behind in the areas they had swamped. The deposits of mud and sand beside the river during flood events form a flat terrain, hence the name floodplain. Sometimes, these level tracts of land extend kilometers away from the main water channel.

Cradles of civilization

Because floodplains are replenished constantly by floods with nutrients from the mountains, they are naturally fertile ground, ideal for planting crops and bumper harvests. Floodplains are preferred sites for settlements because they are near the source of water. Man has chosen to live on these flat fields because of its practical and economic value.

The great civilization of Mesopotamia was cradled in the Fertile Crescent between the rivers Tigris and Euphrates while Ancient Egypt was beside the Great River Nile. Descendants of these civilizations have not abandoned these places despite the great floods described in the Epic of Gilgamesh or the Great Flood in Genesis. They still inhabit the land and have grown into even much larger populations. Today, these places are still known to experience disastrous floods.

BEFORE and after images of Mandulog River’s mouth and adjacent floodplains. Communities, including rows of houses in Orchids Homes Subdivision, were washed out to sea. photo credit: GoogleEarth

Floodplains, by the way, are not the only regions that are extremely fertile. Soil at the foot of volcanoes are also rich. They yield bumper crops and are ideal for habitation. Cities started to develop in these areas because vital agricultural lands were enriched with minerals every time the nearby volcano erupted. Even habitation of the mountains was driven by the need to exploit nature’s bounty. San Francisco, on the west coast of the United States, flourished because of the gold rush.

The development of Baguio was not purely driven by its vacation value. It was because of gold and copper in the earth. These metals were brought to the surface along faults, the very same fractures that move and wreck the bountiful land. The same processes that give Earth its richness are the same processes that devastate the land. For this reason, cradles of civilization are more often than not naturally hazardous.

Geological consent

Man has this tendency to settle in dangerous grounds, not because they choose to live on the edge but because fertile land sustains life. Many realize that they live dangerously only when disaster strikes, but in the hundred-year interim or so between catastrophic events, life is bliss.

In some cases, great civilizations were entirely wiped out by nature’s wrath in a single day, not because nature is fond to take life but because it has been its disposition for millions of years. Human settlements are fairly recent in Earth time and violent processes that have shaped the planet will not stop because people are in harm’s way. In the words of Will Durant, a poet and philosopher, “Civilizations exist by geological consent, subject to change without notice.”

The 250-350 millimeters of rain dumped on the watershed of Mandulog River by Sendong and the location of the communities in the floodplains were the perfect mix for a disaster. The stream network in the uplands collected rainwater and swelled Mandulog River, generating a flash flood that swept everything in its path.

The river of torrent carried tons of trees and eroded debris cascaded toward the communities of Bayug, Upper Hinaplonan, Hinaplonan and Santiago in Iligan. Floodwaters 7 to 10 meters high rampaged beyond the banks of the river and wiped out villages with incomprehensible force. Little did residents know that such flash floods could be so devastating to completely destroy their communities and shatter their dreams. It took Mandulog River less than five minutes to reclaim her floodplains, land which people appropriated for themselves.

By swimming from one neighbor’s rooftop to the next, Banawa and his two children were lucky to have survived. He is doubly lucky that his wife, who clung on the ring of a basketball court, also made it unharmed. It is a miracle they were not hit by any of the thousands of rafted logs. Many others, including most of the 500 families beside their subdivision in Orchid Homes, were not as fortunate. That village is now barren with numerous cement stumps, the foundation remnants of houses.

Structural solutions

What could have the residents done to avoid this misfortune? What could government have done to prevent all this from happening? To stop the destruction of freak nature is a dream for many. Engineering solutions such as dikes work most of the time but not all the time. They fail to protect communities especially during extreme events.

I have seen this everywhere in the Philippines: In Cabalantian, where waters breached the Gugu dike and swamped the town on the early morning of Oct. 1, 1995 as Typhoon “Mameng” ravaged Central Luzon, leaving 100 people dead; in Albay, where several dikes of Mayon volcano were breached upstream and floodwaters and lahar killed 1,266 people in downstream villages in 2006; during Tropical Storm “Ondoy” when dikes built to protect Provident Village in Marikina City failed, killing people; in Pampanga and Bulacan, where the more than P1-billion Pampanga River Delta dike, built to protect Sulipan/Calumpit, contained floodwaters generated by “Pedring” and “Quiel” in Hagonoy and Calumpit for weeks.

The list goes on and on and there can only be one conclusion. There are limits to technology and human foresight when dealing with the lethal impact of natural hazards.

Dams

One proposal to address the problem of Iligan is to construct a dam upstream of Mandulog River. Dams serve to provide irrigation and electricity, be they reservoirs for potable water or flood-control systems. This solution, however, is not feasible for Iligan. Lawrence Cruz, the mayor of Iligan, did not mince his words when asked about constructing a dam to hold floodwaters. His point blank answer was, “No, that is not an option.”

There is good reason for his retort: apart from displacing upland settlers and overcoming political obstacles, current-dam protocol is more geared toward generating income for its operator rather than for the protection of people from floods. We had problems with the San Roque dam during Typhoon “Pepeng.” The dam released 5,000 cubic meters per second of water for hours, inundating vast areas of Pangasinan. The protocol on the release of water remained unchanged up to the time of Pedring and Quiel. There seems to be no prospect for change.

Flood-control system

I’ve also seen proposals for the installation of numerous smaller dams to be distributed throughout a network of streams in a watershed. Aside from generating electricity, the dams will act as a flood-control system. Building many small dams instead of a single dam 100 meters high is less threatening to populations in low-lying areas and more environment-friendly. However, their effectiveness as a flood-control system has yet to be tested in a tropical region, hit on average by 20 typhoons annually.

A dilemma facing the mayor of Iligan is whether to allow resettlement of the devastated areas or to declare them uninhabitable zones. This question is extremely tough for a politician because the land has property value, a factor in the decision-making process that can’t be easily dismissed. By allowing resettlement, survivors can pick up the pieces of their shattered lives and rebuild their homes with hopes that good times will roll again. Chances are the community will be vibrant again and will be for some time until the next deluge comes.

By that time, the resettled area would be more developed and the population would have increased. If the next generation forgets and becomes complacent, which most likely will happen considering how we communicate hazards, a future disaster would be worse with many more fatalities than Sendong’s.

The other option of classifying devastated areas as permanent danger zones and relocating survivors seem more sensible in the long run. Relocation sites, however, must be properly assessed for all geohazards and there must be provisions for displaced residents to earn their livelihood.

Development issue

Disasters result when there is failure in development planning. Catastrophes are a natural part of the Earth’s system and the only recourse for communities to endure is to be smart in dealing with hazards. By smart we mean that we need to understand, learn from the past and use the best science and technology to promote resiliency against disasters. It is imperative that we settle in places that are identified as least compromised and not in areas that are naturally hazardous. If we insist on living in hazardous places, we must understand the risks and be aware of the consequences!

The Sendong disaster was among the disasters that recently plagued the Filipino people. It was the third big one in 2011. With the Durian, Ondoy, Pepeng, Juaning, Pedring and Quiel disasters, the track of the storm and the watershed where it dumped heavy rainfall were the common factors of the floods.

Awareness

The next perfect storm can strike in any of the watersheds in the Philippines and bring forth a deluge in the floodplains. It’s a Russian roulette, and many are sitting ducks just waiting for the next deluge.

Do you know in which watershed you live and if you are in a perilous floodplain? Have you bothered to look at a hazard map and learn the evacuation plan, if there is any at all? Awareness is the first step. It is up to you to do the next smart move.

(Lagmay is a professor at the National Institute of Geological Sciences, University of the Philippines. He conducts research on natural disasters and strongly advocates the use of advanced science and technology to mitigate natural disasters. You can follow him on Twitter @nababaha.)