Urgency, not hurry

Last week, I sat down with Doc Sio, aka Dr. Norman Dennis Marquez, our university physician and mentor of our health sciences majors.

Many of his former students have gone on to become doctors and public health workers. I’ve also been teacher and friend to some of these majors, and they bear echoes of his mentorship when they’ve taken his lessons to heart. They are calm, loving, empathetic.

I felt that same tranquility as Doc Sio and I discussed our increasingly short deadlines and heavier workloads. He recognized that, indeed, for a university to work within larger bureaucratic structures, it needed to follow strict deadlines for all its tasks. However, if people were given mere days to finish urgent work, then the hurry would simply lead to more mistakes.

Article continues after this advertisement“I don’t stress myself with deadlines,” he said, “I do my best to meet them, given their real urgency. I give a premium to quality and accuracy.”

It became the heart of our conversation, as Doc Sio spoke about why hurry and urgency were so easy to confuse with each other. Urgency, he said, is about values: there are many things of great urgency that must be addressed, but they shouldn’t be solved in a hurry.

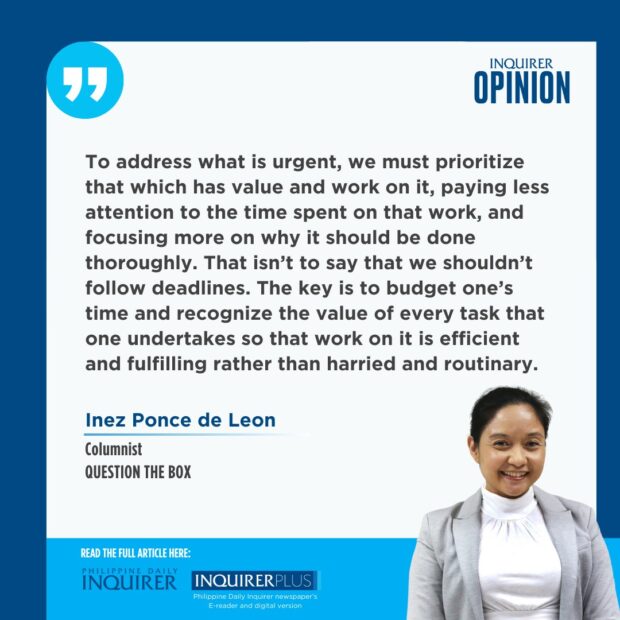

Hurry, in contrast to urgency, is about ticking items off a to-do list. To address what is urgent, we must prioritize that which has value and work on it, paying less attention to the time spent on that work, and focusing more on why it should be done thoroughly.

Article continues after this advertisementThat isn’t to say that we shouldn’t follow deadlines; I would be the last person to say that, and especially to my students. The key is to budget one’s time and recognize the value of every task that one undertakes so that work on it is efficient and fulfilling rather than harried and routinary.

To explore this reasoning, let’s examine the urgent problem of education.

Our students have ranked low on international standardized tests for decades, and these tests might be taken as one among many indicators of our students’ ability to think critically, listen, and read rather than impose and insist on their views, and solve problems carefully.

It is an urgent problem because we need citizens who can solve problems while recognizing the country’s ills and blessings. We need citizens who listen to people and celebrate diversity rather than bury it beneath some immature exhortation to protect a supposed way of life by erecting borders, both real and imagined.

Solving the education crisis in a hurry has led to several disasters, especially when the fastest solution is to simply spend more money without meticulous, no-nonsense audits.

We’ve already seen how a lack of policing of government funds has made officials opaque about their dealings on the pretext of security, protection of interests, or maybe even protection of their families from conviction by international judicial bodies.

Real solutions take time not because the people involved in them are lazy, but because it takes time to capacitate communities, make them recognize that they have the power to change their lives and work with the government, and help them organize themselves so that they can take charge of their problems.

This is true empowerment, and it is difficult to achieve when local governments like to make people dependent on aid and relief as insurance for votes in the next election. Once again, a solution of hurry (promised aid and relief) instead of a solution based on values and principles to tend to an urgent problem (genuine community empowerment to solve larger problems like education).

In last week’s column, I gave an example of an education-related solution that takes time: Fr. Ben Nebres’ feeding programs, which have been tending to poor students in public schools for decades, and which work with communities to facilitate the delivery of food aid so that students’ brains can develop and the students can think well in school.

It is a long, slow solution to an urgent problem, but these feeding programs are now instituted in many communities across the country. The program first needs a community to be capacitated: to take ownership of a problem, welcome a solution, and contribute to tailoring the feeding program for implementation in the community. With this approach, the solution lasts far longer than a program that orders people around and tells them what to do, how to think, or how to vote.

Such imposed programs often take little to no account of the deeper aspects of community needs and identity. Such programs are among those implemented in a hurry, with the illusion that they will solve problems quickly; but because they’re built on saving time rather than the values of a community, then they also get shelved faster.

It is in these cases that we see the wisdom of taking time to understand and solve an urgent problem. By attacking an urgent problem in a hurry, the only thing we address is our perspective of the problem. The only question the hurry answers is, “What can I remove from my to-do list so that I can do something else?”

iponcedeleon@ateneo.edu