Old-fashioned vs online research

I often remind my students that there is a lot more to the internet than online shopping, TikTok, reels, and porn. If I had the internet in college, I would have hit the ground running when I started writing on Philippine history for the Daily Express Weekend Magazine in 1985. If I had a smartphone or laptop earlier in life, I probably would be better than I am today. When I visited the Daily Globe in 1987 for my job interview, I remember how the newsroom was divided: half on the left side of the room physically pounding on typewriters, making noise as their copy evolved, while those on the right side worked quietly on computers, using the complicated dinosaur of a program called WordStar.

Thanks to an expatriate uncle who passed on his office-issued Mac to me each year when he visited Manila, I was using Apple and Word from my senior year in high school. When I went to college, a professor returned my paper because it was not “typewritten” on bond paper. I used a dot-matrix printer on continuous paper. A Macintosh was merely a word processor, research meant going to a library or archive to access physical books and manuscripts. Without the internet, I learned to follow a lead, build a story with factual research, find an angle that would make my narrative engaging, then write a text with a beginning, middle, and an end. I did background research and never started an interview, with Nick Joaquin for example, with “Can you tell me what you wrote?”

My friend, the eminent historian Rolando Borrinaga, recently posted a slide on Facebook that declared, “Some teachers of history courses mistake their students for journalists. I just refused another request for interview.” As someone who receives his fair share of online interview requests, I share Borrinaga’s unjust vexation. It seems that some college-level history teachers presume that the basics of the research paper have been covered in K-12 and need not be repeated or reinforced. Not so as I often have to teach students proper citation, or even how to use an Index to a multi-volume work. Many students have to be instructed to visit the library and handle a physical book because they must learn that not everything can be found online.

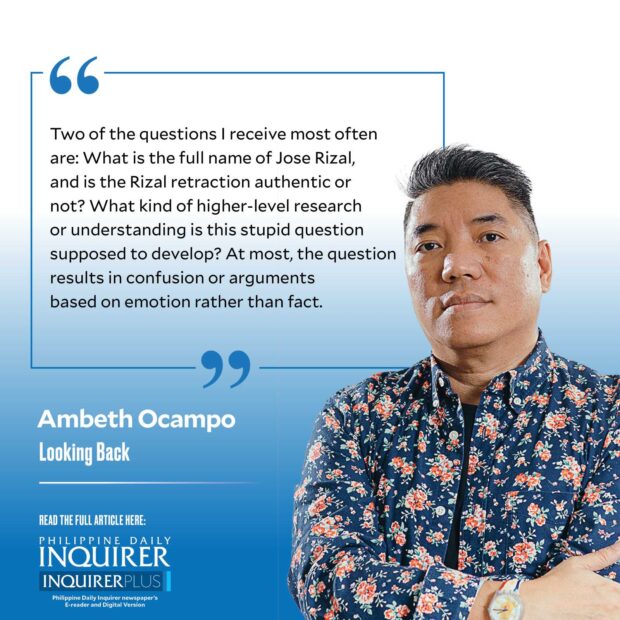

Article continues after this advertisementTwo of the questions I receive most often are: What is the full name of Jose Rizal, and is the Rizal retraction authentic or not? I do not see the point of knowing Rizal’s name on a baptismal or civil registry when he identified himself as “Jose Rizal” or simply “Rizal.” There is no record or signature in his hand that states “Jose Protacio Mercado Rizal y Alonso Realondo (sic)” (it should be “Realonda”). What kind of higher-level research or understanding is this stupid question supposed to develop? The Rizal retraction is an ongoing debate by people who insist that the document in the archives of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Manila is a forgery despite it being written in Rizal’s hand as authenticated by two witnesses after he wrote it. What does this research question hope to achieve if the students are not familiar with Rizal’s handwriting or his life, and are not given physical access to the document in question? At most, the question results in confusion or arguments based on emotion rather than fact.

Those who actually use a library for books rather than an air-conditioned place to study or chill locate a book from a shelf using an online public access catalog that coughed out call numbers based on a search by author or title. People born in the last century had to consult a card catalog, a series of cards on long, pullout drawers that were arranged alphabetically by author, title, or subject. It was never a waste of time to patiently sift through cards to find the book you needed because the process showed you many other books, sometimes a book you were not looking for that turned out to be more relevant than the one you were initially looking for. I would like to think that it is this old-fashioned analog research that defined how I use the internet.

When I do a Google search, I do not take the result at the top of the thread mindlessly, rather I scroll and read every search result until the end before choosing, by elimination and validation, what I think to be the best suggestion. The same goes for physical dictionaries or encyclopedias that have since been discarded from libraries in exchange for online sources and subscriptions. While an online search may be faster than going through other words and entries, everything that comes along the way expands your field of vision. I may have been poor at algebra and geometry but these disciplines taught me how to think and order data. The fun was not in getting the right solution to the problem but in writing out all the steps that led to the solution.

Article continues after this advertisementThe Greek word “historie” may sound like “history” but its literal meaning is far from it. It means “inquiry” or more importantly “knowledge from inquiry.” Questions or solutions to the questions can sometimes be more important than the answers.

Comments are welcome at aocampo@ateneo.edu