Building democracy brick by brick

The other week, I spoke before 142 college-level scholars of the DOST Science Education Institute who were undergoing a leadership camp in Tagaytay. The scholars, aged 18-23, were taking science, technology, engineering, and math courses from the University of the Philippines (UP) Diliman, Mapua University, Technological University of the Philippines, and the Rizal Technological University. My topic was “Youth Participation, Citizenship, and Democracy.”

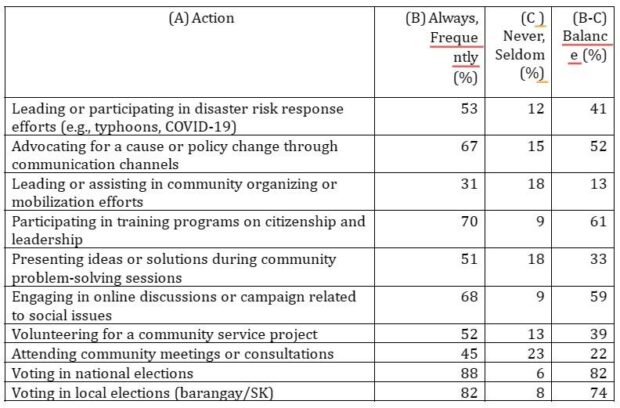

Before the talk, I ran an online Google Forms survey that the scholars answered. The students were asked: “How confident are you in your ability to contribute to solving community problems?” The results are summarized in the table. When the response percentages for “sometimes” are skipped and the “never” and “seldom” percentages (C ) are subtracted from the “always” and “frequently” percentages (B), we get the balance percentages (B-C).

This table shows that youth participation is mostly in the formal processes of voting, with voting balance in national elections (82 percent) oddly more pronounced than voting balance in local elections (74 percent). Engaging in online discussions is the next most pronounced participation behavior of the youth, highlighting the importance of social media relative to face-to-face interactions. Leading or assisting in community organizing or mobilization efforts is the lowest balance (13 percent), but this jumps to 41 percent when it is about leading or participating in disaster risk response efforts.

These results suggest a lack of systemic and purposive efforts to create opportunities for youth participation in the discussion of social and political issues, especially at the local level where their participation should be more meaningful and decisive.

Another question asked in the survey was “What are the biggest challenges you face in trying to participate in the democratic processes in your community, city, or region?”

The main categories of responses related to the “Lack of information and transparency about democratic processes.” As one student said: ”One of the biggest challenges I face when trying to participate in democratic processes in my community is the lack of accessibility and transparency in decision-making. It can be difficult to stay informed about important issues and to have meaningful opportunities to provide input or feedback.”

A second category was the “Lack of resources or time to design and participate in democratic processes.” One student said: “I believe that the most difficult challenge I encountered in that scenario was a lack of financial and human resources. Involving the public in decision-making takes time and costs money and energy. Starting with the planning phase, it takes a significant amount of time to build a meaningful process that can successfully involve individuals and their opinions.”

A third category was “Feeling like their voice doesn’t matter.” One student said: “Sometimes, it is hard to participate in our community because of the age barrier—as a young person I don’t think my voice will be heard. But I think it is also the time to show and voice out and be heard because we are the future of this generation.” Another said: “Sometimes there is a feeling of political apathy among us young people, which can stem from a sense of disillusionment or feeling that our voices don’t matter.” A UP student said: “Biggest challenge I have faced participating in [the] democratic process is the prejudice people have toward students from UP often seen as leftist. The fear of being Red-tagged even at home has always been something that kind of hindered me [from voicing] out in democratic processes.”

These insights from the youth are critical inputs in strengthening Philippine democracy. Too much attention is paid to the national level, and too little to building democracy brick by brick at the grassroots level.

doyromero@gmail.com