Two months ago, the results of the 2022 Programme for International Student Assessment (Pisa)—an international assessment of educational achievement in math, science, and reading—were released to the public. Immediate responses ranged from disappointment to outright panic as a multitude of voices rushed to cast blame and demand change. In this brief note, I suggest that this public handwringing and dismay are both premature and unwarranted. Let’s look at a few facts.

On its website, Pisa analysts point out that between 2018 and 2022, worldwide performance in math (on the Pisa assessment) declined by 15 points and in reading by 10 points. Both were described as “unprecedented” drops over such a short period. In the Philippines, meanwhile, performance in both math and reading over this period improved by 2 and 7 points, respectively, while science saw a decline of 1 point. In sum, while much of the world saw major declines in learning, the Philippines actually managed a positive gain.

Or consider the case of Indonesia, a country with many cultural, linguistic, and economic similarities with the Philippines. Between 2015-2016 and 2021-2022, Indonesia experienced a decline of 20 points in math, 38 points in reading, and 20 points in science. In a similar period, the Philippines held steady or showed some gains.

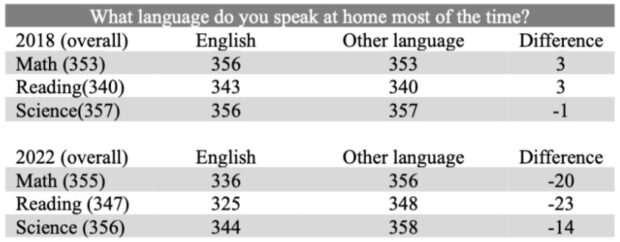

Several striking features of the Pisa report on the Philippines can be seen in the following table.

First, students who said they speak primarily English at home showed a significant decline in performance between 2018 and 2022 ranging from 12 points in science to 20 points in mathematics. Secondly, students who reported speaking a language other than English at home showed gains in all subjects ranging from 1 point in science to 3 points in math and to 8 points in reading from 2018 to 2022. Third, while the difference in performance on Pisa between these two groups was minimal in 2018, it was quite substantial in 2022 ranging from 14 to 23 points—a massive improvement compared to what has happened in Indonesia.

What can we conclude from these data? The one major educational innovation in the Philippines in the last 10 years has been the introduction of L1 instruction. Students who were 15 years old in 2018 had completed their first four to six years of education before the implementation of L1 instruction so their performance did not reflect the educational impact of L1 instruction. On the other hand, many of those taking Pisa in 2022 had at least some exposure to L1 instruction (MTB-MLE). Since it was the nonspeakers of English whose performance improved (even though the Pisa test was in English), a reasonable conclusion is that this innovation was a major contributor to the improvement in performance seen in the table.

If, as Pisa reports, there was an “unprecedented” decline in scores across participating countries between 2018 and 2022, yet the Philippines showed positive gains during the same period, it would seem that the Philippines was doing something right in the lead-up to Pisa 2022. Thinkers and policymakers should be appreciative of the gains made and eager to take up the many challenges of further improving educational outcomes in the country.

Dr. Steve Walter (steve_walter@diu.edu) is an associate professor in the Department of Applied Anthropology at Dallas International University in Dallas, Texas. He has made numerous trips to the Philippines and has closely followed the current debate about the language of instruction as a part of the Philippine MLE Discussion Group.