Early in my career, I built a reputation as an iconoclast. Revisiting the past and debunking what people previously believed to be true was a joy, until 2002. With the stroke of a president’s pen, I was appointed chair of the National Historical Institute (NHI), and overnight became the guardian of the official history I often questioned. That is one of the ironies of my life. To be fair, many things I had to unlearn from basic Philippine history did not come from textbooks nor my teachers, they were absorbed from other sources.

In an age before smartphones, short messaging service, email, Messenger, Viber, and WhatsApp, people communicated via “snail mail.” Letters and packages sent through the post office were paid the value of postage stamps. One philatelic series carried the “Evolution of the Philippine Flag.” There was no such evolution because the stamps actually represented the different flags of the Philippine Revolution. These included the personal standards of: Andres Bonifacio, Pio del Pilar, Gregorio del Pilar, and Mariano Llanera. The last was the most memorable being the skull and crossbones in white over a black background.

In 1973, the NHI reprinted the 1947 publication of the Library of Congress “Doctrina Christiana: the first book printed in the Philippines, Manila 1593.” Carlos Quirino’s 1960 essay on “The First Philippine Imprints” was reprinted as an introduction to the book. Quirino states that of the three earliest books printed in the Philippines to surface after World War II, two “Doctrina Christiana” (one in Baybayin and the other in Chinese), both published in Manila in 1593, are rightfully the first Philippine books (plural!) printed in the Philippines.

In the 1980s, while working with the original Rizal manuscripts in the vault of the National Library of the Philippines, I was able to prove that an unpublished 245-page manuscript labeled “Borrador del Noli Me Tangere” were not the drafts of Rizal’s first novel, rather these were drafts of a third novel that Rizal attempted, first in Tagalog and later in Spanish. The unfinished novel had no title, except the opening chapter in Tagalog marked “Makamisa” (After the Mass) that has been accepted as its provisional title, until later research and scholarship can provide something better.

I hope my last column on Maynila or Manila without the “d” settles the issue on how to correctly spell and refer to the name of the capital of the Philippines. Controversial issues settled by the National Historical Commission of the Philippines have yet to gain popular acceptance. The Bohol site of the 1565 Blood Compact between Datu Sikatuna and Miguel López de Legazpi has been determined to be in Loay, but people insist on the erroneous site in Tagbilaran marked by a sculpture by National Artist Napoleon Abueva. The site of the 1521 “First Mass” in the Philippines has been declared to be Limasawa by three independent panels convened by the NHI chaired by: Emilio Gancayco (1995), Benito Legarda (2008), and Resil Mojares (2020), yet some people would not take no for an answer. One resorted to spreading his officially unaccepted arguments online, another went to court and sued the historians for doing their job. Fortunately, some corrections have been accepted. The site of the first shot in the Philippine-American War on Feb. 4, 1899 moved from San Juan Bridge, San Juan, to the corner of Silencio and Sociego streets in Santa Mesa, Manila. The Code of Kalantiaw, declared a hoax and without any historical basis in 2004, has disappeared from textbook history. The Order of Kalantiao, created in 1971 by Ferdinand Marcos Sr., and traditionally conferred on retiring Supreme Court justices has been discontinued.

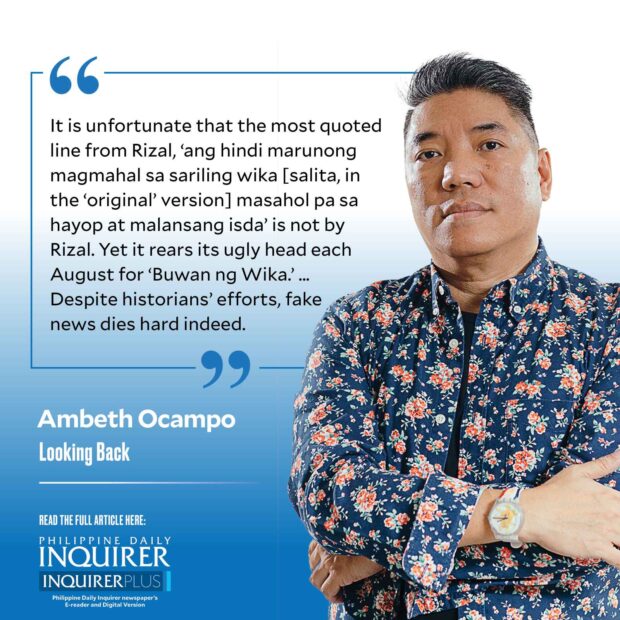

The urban legend on Rizal being the father of Adolf Hitler was shot down by counting nine months from Hitler’s birth to see that Rizal was in London in August and September 1888. He was nowhere near: Austria, the Metropole Hotel in Vienna, or Hitler’s mother Klara Polz. In 2011, I published an article in the Inquirer showing the discrepancies in internal evidence that piled up to disprove that Rizal wrote “Sa aking mga kabata” in 1869 when he was 8 years old. It is unfortunate that the most quoted line from Rizal, “ang hindi marunong magmahal sa sariling wika [salita, in the “original” version] masahol pa sa hayop at malansang isda” is not by Rizal. Yet it rears its ugly head each August for “Buwan ng Wika.” It appears in reviewers for the licensure exam for teachers. Resurrected from the dead, the poem reappeared online recently resulting in Ambeth Ocampo memes, one of them showing me unmasking the true author of the poem as prewar poet and critic Hermenegildo Cruz. I won’t repeat my arguments here, you can access the article in my book “Rizal without the Overcoat” or with this link to the 2011 Inquirer: https://tinyurl.com/3vspxv27

Despite historians’ efforts, fake news dies hard indeed.

—————-

Comments are welcome at aocampo@ateneo.edu