The sugar ‘puzzle’ explained

Imagine drinking coffee without sugar.

Or, should we accustom ourselves to drinking coffee without sugar? It is best for our health anyway as sugar has high glycemic index, particularly refined or white sugar (GI value =65)!

The Philippines has gone from sugar exporting to sugar importing. What happened and why?

First of all, the demand for sugar had increased due to a boost in the country’s population — too many Filipinos – 113 million now, compared to the 1970’s, when we were just 37 million – a 300 percent rise.

This has resulted in an increase in sugar consumption and demand. In the 1970s, our per capita sugar consumption was 15.0 kilograms per year. Now, it is 21.5 kilograms. The country’s sugar demand in the 1970s was only 555,000 metric tons. Now it is 2.42 million metric tons (an increase of 436 percent).

The production/supply side is another factor. In the past, when we were exporting about 1.8 million tons of sugar to the US, we grew sugar cane on more than 500,000 hectares and were producing about 2.4 to 2.6 million metric tons of sugar. These were processed by about 40 sugar mills. Since then, we have lost about 100,000 hectares of sugar lands.

With fewer sugar canes to mill, 15 sugar mills closed down leaving only 25 mills operating and distributed as follows: 13 mills in Negros, 2 mills in Luzon, 4 mills in Panay, 3 mills in Eastern Visayas and 3 mills in Mindanao.

For crop year 2022-2023, the estimated sugar yield is only 1.85 million metric tons of sugar, 30 percent less than what we produced during the heyday of sugar production in the country.

What explains this decline?

Climate change leading to declines in sugar yield constitutes another factor which did not exist in the 1970s. Super typhoons, e.g., Odette, destroyed sugar cane fields, decreasing sugar yield by more than 150,000 tons of sugar in crop year 2021-2022.

So, we started importing sugar. Harvesting canes is fast becoming a challenge. Big combine machines for harvesting cannot be used during the first and second months of harvesting due to rains. It is still rainy in October and November, the start of milling in any given year which may even extend until January.

This coming crop year, drought via the El Niño phenomenon will again surface affecting cane growth, thus decreasing further sugar yield. Expect more sugar shortage next year, thus, more sugar imports.

Geopolitical factors also intervened.

The Russia–Ukraine war triggered an oil price increase, increasing the logistics cost of production (land preparation, hauling canes to the mill), and it tripled the price of oil-based inputs such as fertilizers.

This forced sugarcane planters to undertake cost-cutting measures by not applying sufficient amounts of fertilizer.

As the war in Europe drags on, the cost of production inputs (fertilizer and diesel oil) keep rising and yields per unit area continue to fall.

To add to the problem, majority of the remaining sugar mills are centenary and their boilers are antiquated. Thus, their sugar juice extracting capacities have declined, giving low sugar recovery to the sugar millers.

Only 4 or 5 of our sugar mills give comparable sugar recovery of 2 bags of sugar per ton of milled cane compared to the more modernized sugar mills of Thailand, from where we now import sugar.

Luzon sugar may be gone in a few years. All the 3 sugar mills of Pampanga have stopped operating. The lone sugar mill of Tarlac is only operating 40 percent (400,000 tons) of its optimum rated capacity due to lack of canes to mill.

The biggest sugar mill in Batangas (Central Azucarera de Don Pedro – CADP) shut down effective January 2023. The remaining smaller sugar mill in Balayan may operate until August to finish milling all the canes which would already be overmature by that time.

Of the 20,000 hectares grown to sugarcane in Batangas (plus small areas in Cavite), 5,000 hectares are mostly planted by agrarian reform beneficiaries who may no longer be planting sugarcane next year. Why should they? Where will they mill their canes?

In short, sugar supply is in peril or in extreme shortage next year and in the coming year. Negros should increase yield from 60 tons per hectare to 80 tons of cane per hectare. Mindanao should up its production from 50 tons/ha average to 70 tons. Will they be able to do all these next year? The answer is “no, they cannot.”

Labor costs are also increasing. Our farm lots are small and many of our sugarcane farms are in sloping areas where yields are lower. About 75 percent of sugar farms are less than 5 hectares in size while another 11 percent are between 5 and 10 hectares.

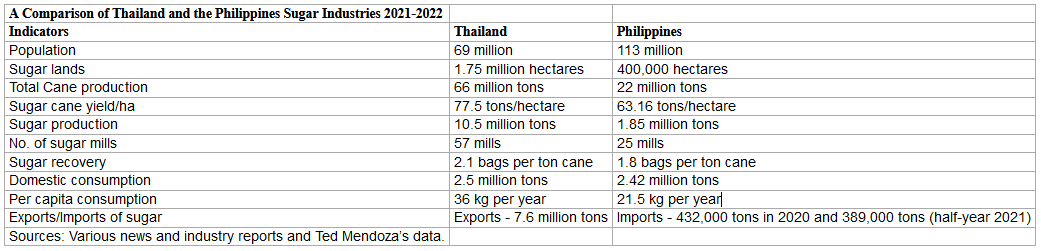

A cursory comparison with Thailand reveals the sad state of the Philippine sugar industry (see table below). As of 2021-2022, Thailand has a population of only 69 million, 40 percent less than the Philippines. It has 1.75 million hectares of sugarcane fields, 3 times more than the Philippines. Total Thai sugar production is 66.3 million metric tons of sugar cane and 10.5 million metric tons of sugar, 3 times more and 6 times more than the Philippines respectively. Sugar cane yield is 77.5 tons per hectare, 14 tons more than the Philippines’.

Thailand has 57 sugar mills, more than twice that of the Philippines. Sugar recovery in Thailand is 2.1 bags (1 bag=50Kg) per ton of milled sugar – 14.3 percent higher than the Philippine output. Tonnage yields in Thailand is also higher (77.5 tons cane /ha vs. 63.16 tons cane/ha. Total domestic consumption however, is almost equal between the two countries.

But Thailand’s per capita consumption at 36 kg per year is 15 kg more than the Philippines’. Thailand exported 7.6 million metric tons in 2021-22 while the Philippines imported 432,000 tons in 2020 and 389,000 metric tons during the first half of 2021 – almost all from Thailand.

Thailand has also suffered from the effects of climate change. Drought and water shortages, excessively heavy rainfalls and rising temperatures have all forced sugar planter/farmers to undertake climate resilient and sustainable production practices to lessen the effects on sugarcane production.

Prices of oil and fertilizers have also zoomed in Thailand. Logistical costs including transportation have also been challenging especially for small sugar farmers. Further, 80 percent of sugar farms are small-scale ranging from 0.16 to 9.44 hectares.

Despite being faced with some of the more difficult problems of sugar production as the Philippines, Thailand managed to still come out on top. It exports almost 70 percent of its production and has become the world’s second largest exporter of sugar.

How do we address the Philippine sugar problem? There are two solutions that we can briefly propose. The most obvious solution is to increase sugarcane yield. But how will the planters do it considering the constraining factors mentioned above?

The second option is to drastically modify review and overturn our existing sugar consumption pattern.

If we can at least go back to the 15 kg per capita consumption in the 70’s, we need to produce only 1.7 million tons of sugar per year. We can do this by eating less sweetened foods – colas, pastries, cakes, candies, etc. And this which would even be good for our health.

(Teodoro C. Mendoza, Ph.D., is a retired Professor and UP Scientist, Institute of Crop Science, University of the Philippines Los Baños. Eduardo C. Tadem, Ph.D., is Professor Emeritus of Asian Studies, University of the Philippines Diliman.)