.

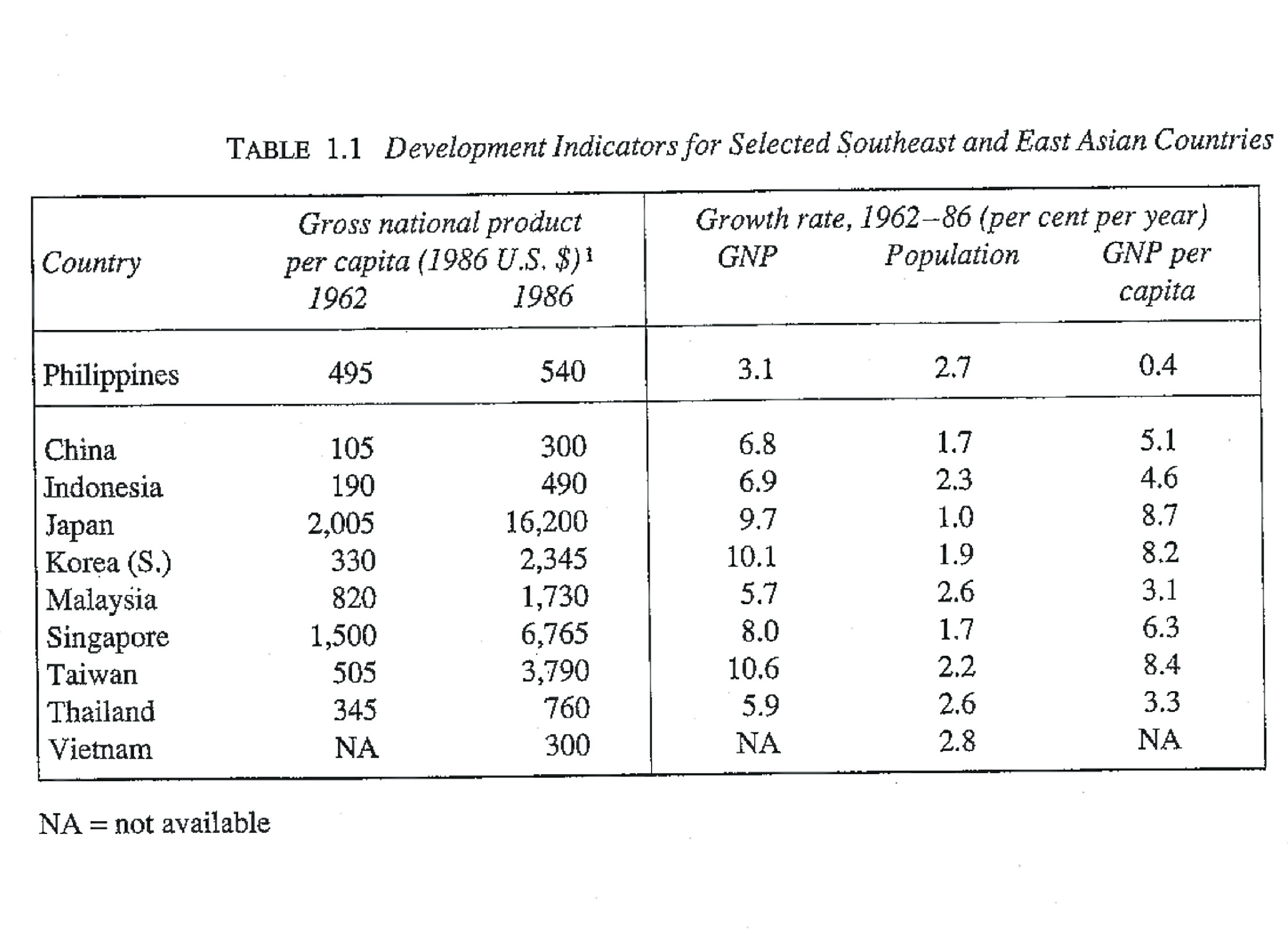

Jakarta—Exactly five decades ago, the Philippines was head-and-shoulders above its biggest immediate neighbor, Indonesia. As economist James Boyce notes in his definitive book, “The Philippines: The Political Economy of Growth and Impoverishment in the Marcos Era” (1993), our per capita income in 1962 was almost $500, more than twice that of neighboring Indonesia ($190).

As for China, which would soon turn into the most dramatic capitalist expansion story in human history, its per capita income was almost a fifth ($105) of that of the Philippines. Astonishingly, back then, an average Filipino was as wealthy/poor as his Taiwanese counterpart ($505), but clearly better off than his South Korean counterpart ($330).

Although relatively poor compared to industrialized nations such as Japan (per capita $2,005 in 1962), the Philippines still boasted one of the region’s biggest economies, albeit with a lower per capita than smaller neighbors Malaysia ($820) and Singapore ($1,500).

Back then, ours were the most fashionable streets, the most glamorous national airline and airport, and arguably the most admired regional culture. The Philippines was also wealthier than most of its neighbors.

During the Diosdado Macapagal administration, and especially thanks to the indefatigable technocrat Cornelio Balmaceda, the Philippines managed to beat rivals in Seoul and Tehran in its bid to host the headquarters of the Asian Development Bank.

Two decades later, the Philippines had barely developed at all. Between 1962 (under Macapagal) and 1986 (fall of the Marcos regime), our country posted only a 0.4 percent growth in gross domestic product per capita rate, largely thanks to the toxic combination of inept governance, poor economic policies, chronic corruption, and demographic explosion.

Meanwhile, in neighboring Indonesia, which was also under a dictator (Suharto), average per capita growth was more than 10 times higher (4.6 percent). The number is even more dramatic in Northeast Asian countries of China (5.1 percent), South Korea (8.2 percent), Japan (8.7 percent), and Taiwan (8.4 percent). In short, our strongman was the weak link even among his regional peers.

Sadly for the Philippines, most of its post-dictatorship leaders were also incompetent. As emerging markets guru Ruchir Sharma notes in his book “Breakout Nations: In Pursuit of the Next Economic Miracles” (2013), by the late 2000s, Indonesia had overtaken the Philippines in per capita income for the first time in history—a feat that would be replicated by Vietnam with the Philippines under Rodrigo Duterte. Only under Benigno Aquino III and Fidel Ramos, who oversaw sustained growth and democratic reforms, did the Philippines manage to largely keep up with its peers.

Over the past week, I had the privilege of witnessing the dramatic transformation of Indonesia, from the tropical paradise of Bali to the megacity of Jakarta. From new airports to shiny roads and a state-of-the-art digital economy, Indonesia is leaping into the 21st century. The new capital city of Nusantara is expected to be largely fueled by renewable energy and driven by smart technology. Indonesia has rapidly embraced electric vehicle technology, while gradually harnessing its position as a prime source of minerals for EV battery production.

Today, Indonesian President Joko Widodo, affectionately known as “Jokowi,” is one of the most admired leaders in the democratic world and beyond. As this year’s Group of 20 president, he successfully hosted a consequential meeting that produced a détente between the superpowers.

By all indications, Indonesia is no longer, to paraphrase writer Elizabeth Pisani, the “world’s biggest invisible nation.” Its time has arrived. Today, Indonesia is now the world’s third-largest democracy, and, before the middle of this century, it is expected to feature among the world’s four largest economies, just behind China, India, and the United States.

Sure, corruption is still rampant. Institutions are weak. And authoritarian populists, such as erstwhile presidential contender Prabowo Subianto, are eerily similar to our own Rodrigo Duterte. However, as one academic in Jakarta recently told me, “Our countries are extremely similar, but the difference is that in your country, the local political dynasties [which mostly prioritize parochial interests] are also your de facto national elite.”

I must also add that our economic “oligarchs” have also been more rapacious than their Indonesian counterparts, which have moved into higher-end manufacturing and successfully branched out across the region. We clearly need a real trade and industrial policy to transform our national economy, but also a leader like Jokowi, who combines folksy charisma with actual competence and patriotic compassion.

rheydarian@inquirer.com.ph