Over a week ago, four individuals were injured after the Carlos P. Romulo or Wawa Bridge that connected Bayambang, Pangasinan, to Camiling, Tarlac, gave way under the weight of two overloaded trucks. The incident became the latest addition to the depressing list of bridges that collapsed this year alone.

In January, a steel bridge in Majayjay, Laguna crumpled under the weight of a 12-wheeler truck that then fell into a river, injuring four people. In April, the aging Clarin Bridge in Loay, Bohol, that passes over the famous Loboc River gave way, killing four people and injuring 31. Just two months later, the steel Borja Bridge in Catigbian town in Bohol also buckled under, though thankfully, nobody was hurt.

That so many bridges collapsed within months of each other gave urgency to the call this week of Senate Minority Floor Leader Aquilino “Koko” Pimentel III for a thorough and extensive safety inspection of all bridges nationwide.

“The incidents are very alarming,” Pimentel said. “They put doubt on the structural integrity and safety of all our bridges. It is time to evaluate [their] safety.”

Pimentel earlier grilled the Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH) on the incidents during the committee hearing on the agency’s proposed 2023 budget of P718.4 billion, one of the biggest allocations in the proposed national budget of a record P5.268 trillion, 4.9 percent higher than the 2022 budget.

DPWH Secretary Manuel Bonoan initially washed his hands of the incidents, saying that the Clarin, Borja, and Majayjay bridges were all local, and therefore under the jurisdiction of the concerned local government units (LGUs).

This did not sit well with Pimentel, who rightly admonished the DPWH about its responsibility in ensuring that LGUs follow the same engineering and structural standards as those used in national infrastructure. Lives are literally at stake, the senator reminded the agency, which is vested with the primary mandate to “plan, design, and construct national roads, bridges, and flood control projects, and the maintenance and preservation of these infrastructure assets.”

Pimentel said the collapse of the Clarin Bridge that killed four should have been a wake-up call for both local and national governments to inspect bridges that serve as vital links connecting communities to efficiently transport goods, especially in an archipelago like the Philippines.

“Whether it is a local bridge or a DPWH-constructed and -maintained bridge, the government should order a probe and a thorough and detailed assessment of the overall safety of our bridges led by the DPWH,” said Pimentel, who also sought a review of the possible errors in the design, specifications, and construction of these bridges.

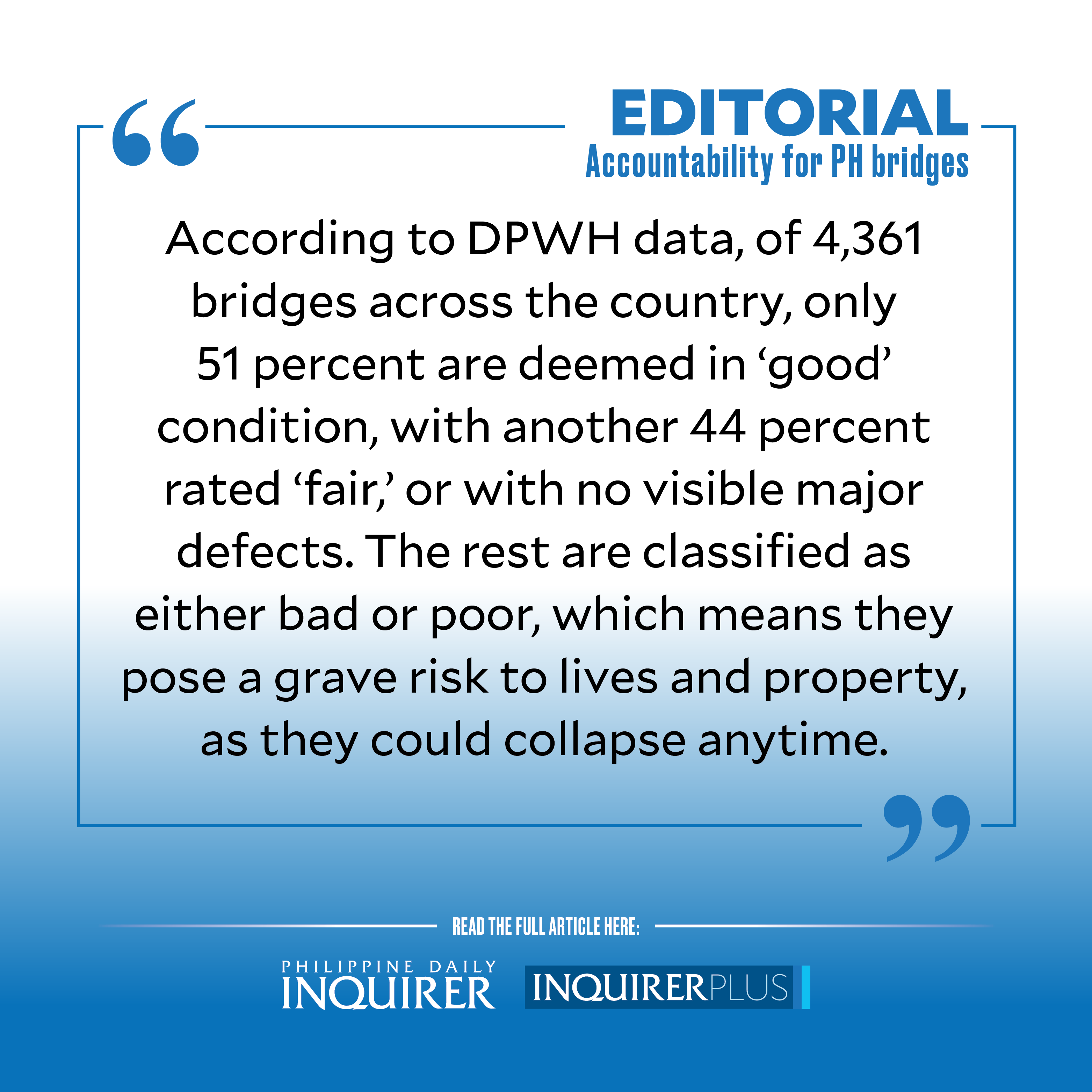

According to DPWH data, of 4,361 bridges across the country, only 51 percent are deemed in “good” condition, with another 44 percent rated “fair,” or with no visible major defects. The rest are classified as either bad or poor, which means they pose a grave risk to lives and property, as they could collapse anytime.

The thorough inspection should be coupled with increasing awareness of, and stricter enforcement by national and local governments, of the weight limit allowed on these bridges. The collapse of the bridges in Laguna, Bohol, and Pangasinan was traced to overloading.

The steel bridge in Majayjay, for one, has a carrying capacity of only five tons, but trucks with far heavier loads regularly cross it until it finally gave way under a truck transporting some 12 tons of sand. The Wawa Bridge, built in 1945 with a load limit of 20 tons, collapsed under the combined load of 69 tons carried by two trucks.

Like people, bridges lose strength over time, pointed out Roy Luna, director of the UP-based engineering consulting firm AMH Philippines.

“Subjecting a bridge to heavy loads more than what the bridge was designed for is causing continuous cyclical fatigue stress. Fatigue makes the structure weak and if it continues, its health deteriorates. Here in the Philippines, the usual fatigue life of bridges is 50-60 years,” Luna said.

The Clarin Bridge was 50 years old and severely damaged by the massive 2013 quake that struck Bohol. It collapsed just two months before the new Clarin Bridge was opened to traffic.

There’s also the issue of prefabricated steel bridges being used longer than they are supposed to, according to Greg Jala, a provincial board member in Bohol who appealed to the DPWH to inspect such bridges installed across the province in the aftermath of the 7.2-magnitude quake in 2013.

Jala said the prefabricated bridges were not intended for long-term use, but were installed mainly to reestablish mobility in the province following the devastating quake. Although prefab bridges are temporary, they have been in use until this time, he added.

Given such concerns, the DPWH, related agencies, and LGU officials must do right by the public and immediately allay their well-founded fears by heeding the call to inspect the country’s national and local bridges.

After all, crossing bridges should not be a death-defying act.