Book hunting used to be a physical activity. One could rough it up and trawl through Recto Avenue to find rare Filipiniana like a needle under a haystack of discarded textbooks. Then, there was Booksale for imported remainders. Here, one could be lucky to find books on the Philippines, and my best finds were in bargain bins in branches outside Metro Manila like Cebu Robinson’s Fuente branch, where there is less competition from fellow academics and bibliophiles.

Things are not the same anymore. Almost everything is done online, with the only physical exertion being typing author, title, or subject; and flicking a mouse or trackpad to search booksellers worldwide. An online search can cough up any book one can possibly desire, with the notable exception of the 1593 “Doctrina Christiana,” preserved in the Library of Congress. Any rare or hard-to-find book can be found with the only issue being the price.

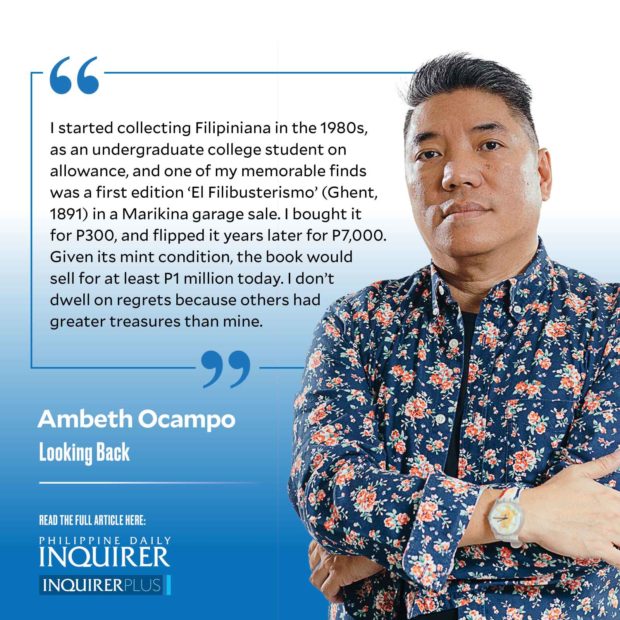

Auction houses have brought book prices to unbelievable levels, and with prices realized appearing online, there are almost no bargains in the world to be had. I started collecting Filipiniana in the 1980s, as an undergraduate college student on allowance, and one of my memorable finds was a first edition “El Filibusterismo” (Ghent, 1891) in a Marikina garage sale. I bought it for P300, and flipped it years later for P7,000. Given its mint condition, the book would sell for at least P1 million today. I don’t dwell on regrets because others had greater treasures than mine. Someone ordered a first edition “Noli me tangere” (Berlin, 1887) dirt cheap from a used bookstore in Ireland. It was inscribed to Rizal’s once and future mother-in-law! Now that is the stuff of legend; beating that is like winning the mega lotto.

I was introduced to Filipiniana—that means books about the Philippines or books by Filipino authors—in college. My literature professors were topnotch: Doreen Fernandez, Soledad S. Reyes, and Marlu Vilches. They taught English and in English, but their instruction was informed by their specialization in Philippine Studies: Fernandez on drama and food; Reyes on the Tagalog novel and popular culture; Vilches had just published an obscure journal on Leyte-Samar studies. Writing term papers for these three professors led me to the Filipiniana section of the Ateneo Rizal Library where I handled old books and periodicals. Not content with that, I developed a lifelong affair with the Lopez Museum. I first visited hoping to catch a glimpse of founding director Renato Constantino, only to be told he had resigned a decade before. Nevertheless, the Lopez Museum taught me all I needed to know about rare books long before my first purchase.

My collecting began at Heritage Art Center run by Mario and Odette Alcantara in 1980. It was an old house, a veritable fire trap, with many rooms filled with many paintings, where one could appreciate art without spending a cent. After class, I spent the afternoons here doing schoolwork or watching Vicente Manansala, Onib Olmedo, Galo Ocampo, and other notables busy at chess. “Mambubulok” would arrive pushing “kariton” full of sacks bursting with books. Mario Alcantara would buy the lot, “pakyawan,” and leave me to choose what I fancied. When I asked for the price, he replied: “Pay me what you think is fair.” That arrangement went on for years. I paid in installments when my allowance came in, and later bartered what I thought was fair.

It seems he didn’t lose money on me. Many years later, he led me to a locked, dark room in the gallery and, switching on the lights, asked, “What do you see?” I scanned the shelves and answered: “It’s a Filipiniana collection.” Alcantara smiled: “This is a shadow of your library. I instructed the staff to list down every book you ever bought and find a duplicate. I did not need to hire a specialist to curate a collection. You did that for me.” Those books, as a collection, were destined for an institutional buyer when the gallery burned down.

Looking back on my life as a bibliophile, I realize that I served as a truffle-hunting hog, sniffing out treasure from trash. As a historian playing “trivial pursuit,” I have been sniffing out meaningful stories from libraries, archives, and museums for 37 years now.

Comments are welcome at aocampo@ateneo.edu