President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. faces the same problems that had confronted our leaders since the country’s independence in 1946, namely: grinding poverty, lawlessness, graft and corruption, and human rights violations. These issues have been discussed at length elsewhere, so let us discuss instead an unexplored obstacle to our development.

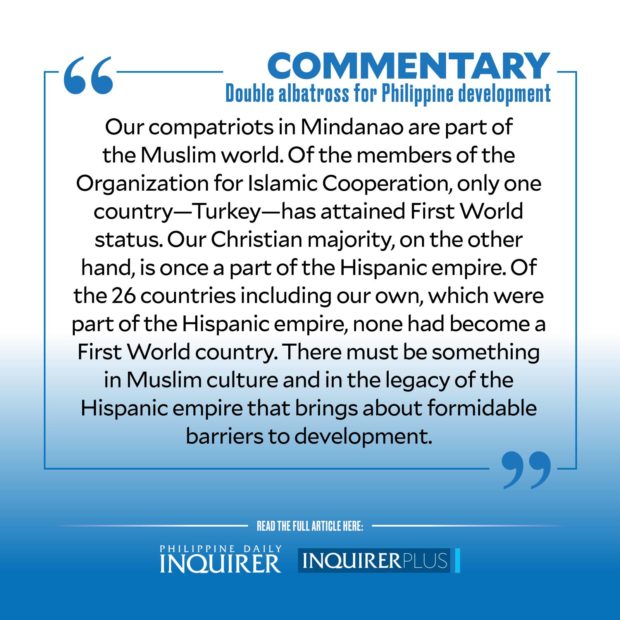

The task of a leader of a Third World country is difficult if an albatross hangs around his neck. It becomes a Herculean task if the leader must bear two albatrosses. The Philippines is in this predicament; it is doubly cursed to be part of two groups that have a dismal record on development. Our compatriots in Mindanao are part of the Muslim world. Of the members of the Organization for Islamic Cooperation, only one country—Turkey—has attained First World status. Our Christian majority, on the other hand, is once a part of the Hispanic empire. Of the 26 countries including our own, which were part of the Hispanic empire, none had become a First World country. There must be something in Muslim culture and in the legacy of the Hispanic empire that brings about formidable barriers to development.

Japan had colonized only two countries, Taiwan and South Korea. Both are now First World countries. Great Britain’s former colonies—the United States, Canada, New Zealand, Australia, Hong Kong, and Singapore—have similarly reached First World status. The first four countries are referred to as countries of “early European settlements.” European institutions were transplanted into these countries, which facilitated their development. However, the last two countries were at one time behind us in terms of development. But they had overtaken us, as did the “tiger cub” economies of Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia, and now Vietnam.

How Turkey achieved First World status is known to all as being the work of Mustafa Kemal Ataturk. The reforms he instituted erased many teachings of Islam. One way Muslim Filipinos can prosper is to select leaders who will steer them to the right path of development. They will need an Ataturk to advance, not leaders like the Ampatuans. Recall that under the Arroyo administration, enormous amounts were bestowed on the Ampatuans. In addition, they had their own private army, manipulated elections, and ran their own system of justice. The powers they enjoyed had surpassed those that will devolve to local officials under a federal system of government. Nonetheless, Maguindanao remains one of the poorest provinces in our country today. Which means that political reforms like federalization will not work if the Muslims among us do not select competent leaders.

With respect to our Christian majority, during this author’s assignment in Chile, there was a symposium on the development of Latin America. In the course of the discussions, the issue shifted into why none of the 26 countries which formed part of the Hispanic empire had become a First World country. Throughout this author’s four-year tour of duty in South America, this was a recurring topic.

One often cited hurdle to development in Latin America is the continuation of the political economy of these countries based on the encomienda system. An encomienda is a land grant from the Spanish monarch usually to a conquistador or a court favorite, giving him authority over a tract of land and the native “indios” (or local inhabitants). The encomienda developed into a self-supporting economic unit with its own set of laws. Since Spain did not have a huge colonial army like the British or the French, each encomienda developed its own armed force. Under the Laws of the Indies, an encomienda was supposed to last only two lifetimes. This was never implemented in both Latin America and the Philippines. The hacendados (our term is “hacenderos”) ruled indefinitely through many generations.

Thus evolved the El Caudillo system, with a hacendado at the head of his encomienda with its own laws, but more importantly, an armed force to protect his domain. When the Latin American countries gained their independence during the Napoleonic Wars, the national governments which evolved were actually a temporary alliance of caudillos. This has remained the pattern of government in Latin America to this day. Since there are so many issues on which such temporary alliance can fracture, the result is political instability. Despite disagreements on several issues, one unwritten rule remains: The participants will not change the social structure of Latin America that upholds the caudillos.

This is a complex topic being presented for the first time, with the author giving one perspective on it. He hopes our academicians and Muslim scholars would elaborate further on how we can overcome these two albatrosses around our neck that hinder our development.

——————

Hermenegildo C. Cruz is a retired career ambassador with 32 years of service in the DFA. He served as ambassador to Chile and Bolivia.