Liminal times

Societies throughout the world have anxieties and fears when confronted with liminality, a sense of being neither here nor there.

Societies throughout the world have anxieties and fears when confronted with liminality, a sense of being neither here nor there.

It can be, for example, the time around sunset, graphically described by the Filipino term “agaw-dilim,” a struggle between day and night, light and darkness. Elders will warn about this dangerous period, of mishaps, accidental and not-so-accidental. Rationally, we can argue that the mixture of light and dark causes the accidents; but might we argue, too, the liminality emboldens men and women with evil in their hearts?

There is liminality, too, in an essay in Nick Joaquin’s “Tropical Gothic,” where he describes a dangerous month of stifling heat amid rains during the month of August, of summer weather persisting in the monsoon. He wrote the piece long before the terrible Plaza Miranda bombing, which occurred on Aug. 21, 1971.

Twelve years later, on that exact same date, opposition senator Ninoy Aquino returned home from exile, only to be assassinated on the tarmac of the Manila International Airport, later to be renamed after him, and now the subject of another renaming attempt by the Duterte Youth representative in the House of Representatives, back to MIA.

Politically, there is the term interregnum, between reigns or regimes, a term originally used to describe the tensions in monarchies between the death of a monarch and the installation of his or her successor. (There is, too, a papal interregnum in the Roman Catholic Church, accompanied in our modern times by frantic speculation on what the next papacy might be like.)

An interregnum can happen, too, in modern societies, between elections and the inauguration of a new head of state. Anxieties escalate in less stable political orders, especially in dictatorships and authoritarian states, much like in monarchies.

I sense such liminal angst in the Philippines right now, marked by people asking, “Has it been 100 days?” the proverbial political honeymoon when citizens are kinder to a new head of state. I did check and as of today, Aug. 23, it has only been 54 days.

If we had a stronger democracy we should not be counting the days, confident that there are enough checks and balances to ensure a smooth transition between leaders, but we are liminal, unsure of what is going on in the corridors of power.

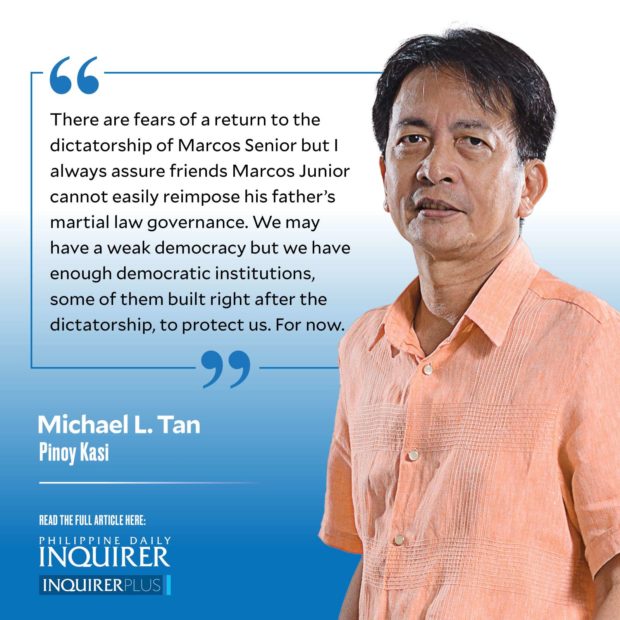

There are fears of a return to the dictatorship of Marcos Senior but I always assure friends Marcos Junior cannot easily reimpose his father’s martial law governance. We may have a weak democracy but we have enough democratic institutions, some of them built right after the dictatorship, to protect us.

For now.

I do worry that, indeed, we live in liminal times and the reason is not so much seeing descending darkness of martial law than the lingering overcast skies of the Duterte regime as in the continuing incarceration of former senator Leila de Lima (crossing the 2,000th-day marker last week), despite witnesses recanting the testimony that had her arrested.

The ominous month of August is not just about Plaza Miranda and the Ninoy Aquino assassination, but also the bloodiest period in Duterte’s war on drugs. The government’s own Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency reported that as of July 26, 2017, this war had resulted in 96,703 arrests and 3,451 deaths of “drug personalities.”

The succeeding month of August was to be marked by long, dark, and bloody nights, swept in by 32 killings in Bulacan on the night of Aug. 14-15, 2017.

A few nights later, the war took a different turn, with the separate murders of 17-year-old Kian delos Santos, 19-year-old Carl Arnaiz, and 14-year-old Reynaldo de Guzman, with the tired bloody script from the police of the victims resisting arrest, nanlaban.

The killings were to continue, even if at a slower pace, and the liminality we have today comes from the long shadows cast by more murderous rampages, which during the pandemic period, were accompanied more often now by Red-tagging.

The liminality comes, too, with a terroristic anti-terror law, introduced during the pandemic and challenged by several appeals to the Supreme Court to declare the law void. Dark clouds are there with signs that the appeals are about to be thrown out.

Our liminality comes as we wonder if, perhaps, we should less be worried about Marcos Junior resurrecting Marcos Senior than Marcos Junior simply allowing the last regime’s dismantling of democratic institutions to continue, even to accelerate.

mtan@inquirer.com.ph