The whole country saw that Marcos fled, and that the obvious reason was his fear of the multitudes of angry Filipinos at his gate.

The turmoil of Marcos’ last years. The Bishops-Businessmen’s Conference surveys of 1984 and 1985 both found 60 percent dislike for Marcos’ power to legislate by decree and to detain his enemies by fiat. Two years of hyperinflation had made three-fourths of all households feel poor. It was no “golden age.”

In November 1985, Marcos called for a “snap election”—a dictator could advance the schedule from 1987—while alleging that the June 1985 BBC survey projected his win. (I assumed he was too smart to misread the survey until, years later, his former executive secretary Alejandro Melchor told me that Marcos was already sick, and may have fooled himself.)

In June, Cory Aquino was less popular than Salvador Laurel, Jovito Salonga, and Butz Aquino. In December, she declared her candidacy for president, with the snap election just two months away.

In mid-February, the Filipino people, as a collective, could not have been sure about the outcome of the snap election, since the Commission on Elections claimed Marcos won, whereas the National Movement for Free Elections’ parallel count said Corazon Aquino won; both gave the winner a clear majority.

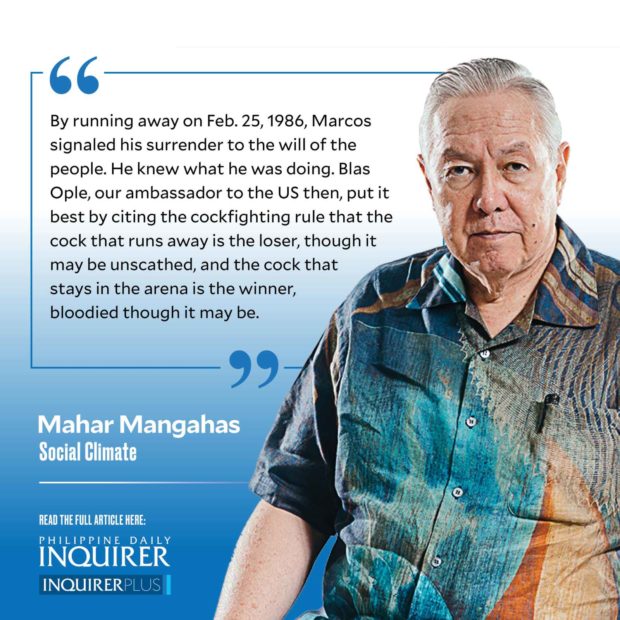

By running away on Feb. 25, 1986, Marcos signaled his surrender to the will of the people. He knew what he was doing. Blas Ople, our ambassador to the US then, put it best by citing the cockfighting rule that the cock that runs away is the loser, though it may be unscathed, and the cock that stays in the arena is the winner, bloodied though it may be.

The restoration of democracy. In May 1986, the Ateneo de Manila University and Social Weather Stations (founded in August 1985) did a joint opinion poll on a scientific national sample of 2,000 adult respondents (2 percentage points error margin), thus providing continuity to the BBC surveys.

The first poll under the new regime, to my knowledge, it was one of four rounds sponsored by the Ford Foundation for research to prepare for the 1987 election. But, having been overtaken by the snap election, its agenda now included the legitimacy of the new government, and related matters.

Asked for the most important source of legitimacy for the government of Corazon Aquino, from a list of eight sources, a massive 67 percent of the sample chose “People Power.” Only 14 percent cited “Aquino’s election victory.” Other percentages were minor: “support of the Catholic Church,” 6; “support of the pro-people military,” 6; “support of the United States,” 4; “support of foreign states,” 1; “support of the communist rebels,” 0.2; and “support of the Muslim rebels,” 0.0.

Asked who won the snap election in their own precinct, 70 percent said it was Cory Aquino.

Asked who they themselves voted for—by writing on a ballot to be put in an envelope unseen by the interviewer—64 percent wrote Cory, 27 percent wrote Marcos, and the rest left it blank.

Thus, it was not only Marcos’ surrender, but also scientific survey research, that validated the election victory of Cory Aquino. The Namfrel count proved correct.

The people’s sentiments toward ex-president Marcos were all unfavorable, except one. Below are Agree-Disagree percentages in the survey for various statements about Marcos’ character, arranged by agreement (missing balances from 100 are neutral or else no-replies):

“A brave president?”: 69-25, Yes. This single pro-Marcos sentiment begs the qualification that he was not brave enough to face People Power himself.

“Favored foreign interests in our country?”: 54-31, Yes.

“His friends enriched themselves from government funds?”: 54-33, Yes.

“A thief of the nation’s wealth?”: 51-34, Yes.

“A deceiver or a liar?”: 51-35, Yes.

“True to the duties of a patriotic president?”: 41-47, No.

“Defender of the poor and oppressed?”: 38-52, No.

“Should Marcos return?”: 29-65, No.

Will the present generation of voters betray the sentiments of the People Power generation, when reminded that Marcos ran away?

——————

Contact: mahar.mangahas@sws.org.ph