Back in 2019, Danielle K. Citron of the Boston University School of Law and Robert Chesney of the University of Texas already concluded that the marketplace of ideas is suffering from “truth decay,” no thanks to technological innovations such as social media that have allowed disinformation to proliferate.

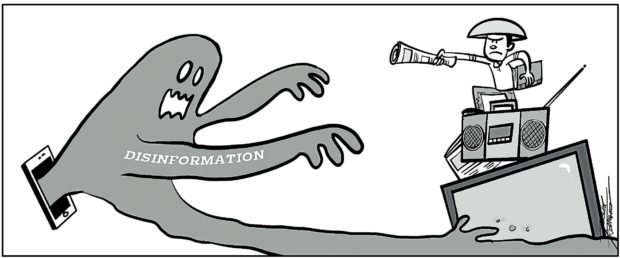

As opposed to misinformation, which is defined as false information spread with no ill intent, disinformation is more menacing as it involves content that is deliberately fabricated, manipulated, and distributed — mainly through social media— with a real intent to harm, such as damage a person’s reputation or distort public discussions on matters of great national significance, like the crucial elections in May.

The risks posed by disinformation to the Philippines’ democratic processes had been deemed so alarming that some of the country’s largest and most respected business groups came together and issued a rare joint statement in December last year expressing alarm over the presence of disinformation and even hate speech in social media and other communications platforms.

The 18 business groups including the Bankers Association of the Philippines, Federation of Filipino-Chinese Chambers of Commerce and Industry, Management Association of the Philippines, Philippine Chamber of Commerce and Industry, and the Makati Business Club said they had “watched with concern” how social media and other platforms had been used to spread disinformation, resulting in “erroneous beliefs, confusion and division.”

“We are losing the trust and unity we need to work together to better our lives, livelihoods and society, especially amid the pandemic crisis,” they said, “We watch with alarm how this abuse has spiked during this election season.”

The groups fear that the damage caused by disinformation “may be long-lasting,” thus their clarion call on political players “to consider what they are doing to the country and to individuals, pledge not to engage in such abuse, and exhort their supporters to remain civil as well.”

Over 100 groups from the academe, civil society, church and media are fortunately pushing back and have mounted various fact-checking campaigns such as #FactsFirstPH, Tsek.ph, Pinas Forward to battle disinformation, which is feared to be very much at play in this year’s crucial general elections.

Cleve Arguelles, lecturer at the De La Salle University’s political science department had said, for example, that disinformation and propaganda were propping up the popularity of presidential race frontrunner Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr., especially among low-income groups who were most “vulnerable” to false information or fake news due to reliance on social media and limited access to the internet where they can access credible information.

This jibes with the findings of a separate survey conducted last year of the Ateneo School of Government that said that those who relied less on traditional media such as television, radio, and newspapers struggled to discern real information, thus more easily fall for or believe in disinformation.

Trust in social media decreases the odds of correctly identifying both real and fake news, according to Ateneo associate professor and researcher Dr. Imelda Deinla. “Trust in social media and Facebook are shown to impair one’s ability to detect misinformation,’’ Deinla said.

In contrast to Marcos, Vice President Leni Robredo has been the disproportionate target of disinformation on social media, according to fact-checking group Tsek.ph.

University of the Philippines’ journalism professor Yvonne Chua told a Senate committee earlier this month that of the initial 200 claims that the group had evaluated, the vast majority were against Robredo.

Indeed, the “speed, scale, and quality” of fake information has been constantly improving, making it even easier for unsuspecting people at the receiving end of the lies dominating social media users’ feeds to believe them.

And when candidates, for example, are confronted with potentially damaging true information, they benefit from the so-called “liar’s dividend” and just summarily dismiss them as “fake news,” products of “biased” media.

Social media platforms have been forced by governments worldwide to take action against disinformation and, to their credit, they have been doing their part in the Philippines.

Facebook, for instance, has taken down hundreds of malicious accounts, pages and groups for “coordinated inauthentic behavior,” suggesting that the conversations are not “organic” or by real people, while Twitter has allowed starting January this year users in the Philippines to flag tweets containing misleading information, among the first countries to have the reporting option.

These are indeed welcome moves which, combined with Filipinos adopting a more critical approach to information to check their veracity, will hopefully lead to better decision-making, especially in the May elections that will determine the country’s course in the next six years.

RELATED OPINION