A taxing dilemma

“To pay or not to pay” is the question that taxpayers must be mulling over these days, just two months before official tax collection season.

The dilemma comes in the wake of Commission on Elections (Comelec) commissioner Aimee Ferolino’s decision junking the disqualification case against presidential aspirant Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr. who, petitioners had claimed, was guilty of moral turpitude for not paying taxes when he was Ilocos Norte governor.

Marcos Jr. was convicted by a Quezon City Regional Trial Court for his failure to file his income tax returns (ITR) from 1982 to 1985. The ruling was upheld by the Court of Appeals.

Ferolino, who wrote the resolution, however maintained that “The failure to file a tax return is not inherently wrong in the absence of a law punishing it.” Her decision finally removed a major obstacle to Marcos Jr.’s candidacy.

No sooner had Ferolino’s Comelec decision been announced than it gave rise to outrage and questions from the public, most of them conscientious taxpayers. Does this mean that it was now acceptable for people to not pay their taxes? Can they cite the Comelec commissioner’s words for not filing their ITR this year? Can they get refunds from their previous tax payments?

In a television interview, former tax commissioner Kim Henares voiced her disagreement with Ferolino’s pronouncement and maintained that Marcos had violated the law for not paying taxes and was convicted, even if the penalty of imprisonment was removed by the Court of Appeals in 1997. “You just have to look at the case number of the Regional Trial Court. It’s a criminal case. You appealed, it’s an appeal of a criminal conviction. It’s just that simple,” she said. Henares challenged Ferolino: “If that is the belief of Commissioner Ferolino, then she should not file [her ITR] and let’s see.’’

So confusing was Ferolino’s reasoning on the Marcos case that the Department of Finance, which oversees the country’s tax collectors, along with a national organization of tax practitioners, had to issue a clarification that the Comelec’s decision was premised on a provision of the law that was applicable in the 1980s, but has long been amended.

The pandemic brought the Philippine economy to its knees over the last two years, and with the devastation came a sharp reduction in tax revenues badly needed for the government to provide Filipinos with basic services. Though economic managers would not say it publicly, the economic contraction is the main reason for them embarking on a record-breaking borrowing spree to make up for weak tax collection.

As the country approaches its annual tax filing deadline in a couple of months, the last thing the government needs is for Filipinos to entertain doubts about the need to pay taxes. There may be no room to entertain doubts among employees whose taxes are withheld at the outset, but like most citizens, they see the Comelec ruling as a bitter reminder of the uneven playing field that is the Philippines’ social structure.

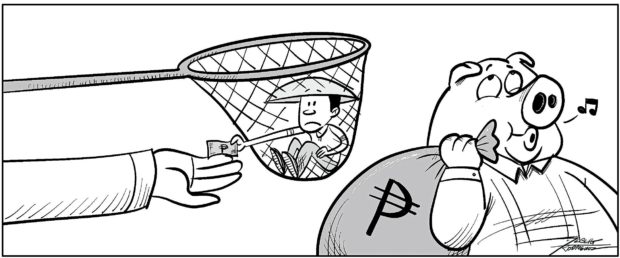

The fact that authorities had to remind people about the necessity of paying taxes highlights the growing belief among Filipinos — and not without basis — that rules apply differently. The weak and the poor are made to account for every infraction, while the rich and the powerful get away with it. This double standard in law enforcement became painfully clear last week with Ferolino’s ruling.

Such is the sorry state of the country’s politics that partisans in the coming elections have started smacking their lips at the imagined prospect of a tax boycott as part of a civil disobedience campaign by a citizenry unhappy with the current state of governance. It might be a personally satisfying comeback at an insensitive bureaucrat, but it would also be like cutting off one’s nose to spite one’s face. Because not paying one’s fair share of taxes is inherently wrong. It would also mean that the government won’t have enough resources to steer the country back to the path of economic growth after the pandemic. That would ultimately bring on higher unemployment rates and dire prospects of economic recovery.

Whether or not the petitioners against Marcos’ candidacy will appeal their case before the poll body en banc or elevate it to the Supreme Court is not as crucial at this point as the government institutions’ move to stop posthaste current speculations on the need to file one’s tax returns.

In the end, it will be the Filipino voter who becomes the final arbiter on which candidate has the moral turpitude and the skills to take on the monumental task of governance, including getting the taxpayers’ willingness to pay their due as an expression of trust in the government they elect.