In the eye of danger

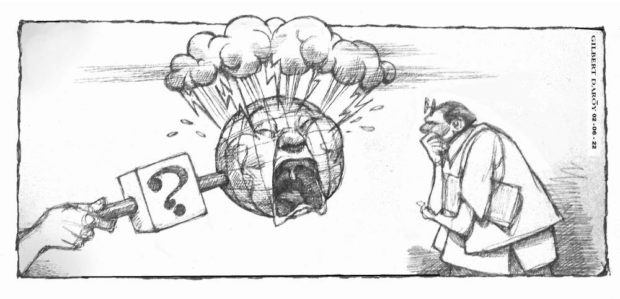

There’s a question that has been rarely posed to candidates running for president but is equally important: What is their disaster risk reduction and management plan?

Examining a presidential aspirant’s disaster-related program is necessary because the Philippines sits along the Pacific’s typhoon belt and the “Ring of Fire,” making it vulnerable to natural disasters: an average of 20 typhoons hit every year and there are 53 active volcanoes scattered across the archipelago including Mount Pinatubo that’s considered among the world’s most dangerous. The recent volcanic eruption in Tonga, an archipelago like the Philippines, has shown that disaster preparedness saves lives, and should be a salient feature in the platform of anyone applying for the highest position of the land.

The world’s strongest storm in 2021, Supertyphoon “Odette,” hit the country last December, killing at least 400 people and damaging more than P23 billion worth of infrastructure and agriculture. In 2020, Taal Volcano, one of the country’s most active volcanoes, erupted after 42 years, sending an ash column as high as one kilometer and placing the surrounding area under alert level 3. Last month, the volcano recorded phreatomagmatic eruptions that were considered “very weak” with the Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology (Phivolcs) assuring nearby communities that any future eruptions will not be as severe as the one in 2020 even as the area continues to remain under alert level 2.

But nature is highly unpredictable as shown by the recent eruption of Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai, Tonga’s underwater volcano that has been inactive since 2014. The volcano erupted on Dec. 20, 2021, but was declared dormant last Jan. 11 after volcanic activity on the island decreased. On Jan. 14, a large eruption happened, followed by an even larger one the following day, with the explosion echoing to as far as Samoa, Fiji, Vanuatu, and New Zealand, where the so-called sonic boom was heard about two hours after the event. It triggered tsunami warnings across the Pacific and waves were recorded for thousands of miles away, as far as the United States’ West Coast, Peru, New Zealand, and Japan.

Now scientists have pointed out that existing forecasting models and warning systems were unable to account for the boosting effects of the shockwave from Tonga’s volcanic eruption, thus information on when the waves would hit land was not accurately timed. Following what happened, experts have pointed out the need to re-evaluate tsunami hazards for other volcanoes around the world, keeping in mind that tsunami warning systems are programmed to prioritize seismic events more than volcanic activities since volcano-triggered tsunamis are rare.

Tsunamis are just as rare in the Philippines but they could be devastating—an earthquake along the Cotabato trench generated a tsunami whose waves went as high as nine meters in August 1976, killing 8,000 people. In more recent memory, there was the storm surge brought by Supertyphoon “Yolanda” in November 2013. More than the rain, it was the surge that damaged 90 percent of structures in Tacloban City and caused about half of the 6,000 deaths because residents, despite evacuation orders, did not understand the danger. Thus, there is much to learn from Tonga which provides regular tsunami drills so that Tongans knew what to do when disaster struck last month. The Polynesian kingdom of more than 170 islands has been described as a flat land with no tall structures or mountains to slow down or block the oncoming waves so people, particularly those on the main island Tongatapu that bore the brunt of the calamity, had to run inland to save themselves. Yet despite reporting that 84 percent of its population was affected by the disaster, deaths were kept down to five.

In 2018, Phivolcs director Renato Solidum Jr. reiterated that Filipinos should prepare not only for earthquakes but other hazards like tsunamis. “The next disaster strikes after we have forgotten the last one,” Solidum said, quoting an old Japanese proverb. The institute reported in September last year that the country now has a total of 111 facilities in its seismic network, including 75 satellite-telemetered seismic stations; 29 staff-controlled seismic stations; and seven volcano observatories. But disaster monitoring work never ends and covers not just earthquakes but typhoons, too. It also entails regular updates of expensive state-of-the-art equipment as well as continuous research and development—this would require much-needed funding support from the national government.

Given this and the risks that the country’s geographic conditions pose, disaster risk reduction and management should be an important element in the ongoing scrutiny of candidates applying to be president. How do they plan to improve the country’s disaster response and reduce the impact of natural calamities, especially for Filipinos who find themselves in the eye of danger?