The bishops’ bold move

.

There was a time, dating as far back as the 15th century, when church leaders engaged in the sale of indulgences. As defined, an indulgence was “a way to reduce the amount of punishment one has to undergo (to atone) for one’s sins,” most commonly by way of donations of cash, property, jewelry, and other precious items to the church.

The practice of selling salvation and forgiveness of sins became quite common, especially among the wealthy and the privileged who used their advantage to escape guilt and responsibility for their transgressions. The use of indulgences, it was said, “supposedly absolved one of past sins and/or released one from purgatory after death.”

Article continues after this advertisementThe abuse of indulgences was what led a scholar named Martin Luther to take action against one Johann Tetzel, a Dominican friar, who was said to have preached that “the purchase of a letter of indulgence entailed the forgiveness of sins.” Incensed, Luther drafted a document called “Ninety-five Theses” (lore has it that he posted a copy on the door of a cathedral) calling attention to clergy abuses and leading to the Reformation. This, in turn, led to the establishment of breakaway Christian churches, including the Lutheran church.

The Council of Trent (1545-1563), while asserting the right of the Roman Catholic Church to grant indulgences, nevertheless laid out strict guidelines on the use of this power and cautioned moderation in its use. With the Council describing it as “a most prolific source of abuses among the Christian people,” Pope Pius V abolished the sale of indulgences in 1567.

Through the years, indulgences have fallen by the wayside, as the use of money and/or influence to buy one’s way to salvation was looked upon as unseemly and yes, unchristian. But there exists today a form of “indulgence” in which rich folks, politicians, big businesses or establishments, perhaps out of the goodness of their hearts, or probably by way of their desire to exert influence or improve their public profile, make huge donations to local churches in support of their charitable programs. In exchange, a few influential individuals have been granted Papal Awards and other forms of recognition, while currying favor with local church leaders.

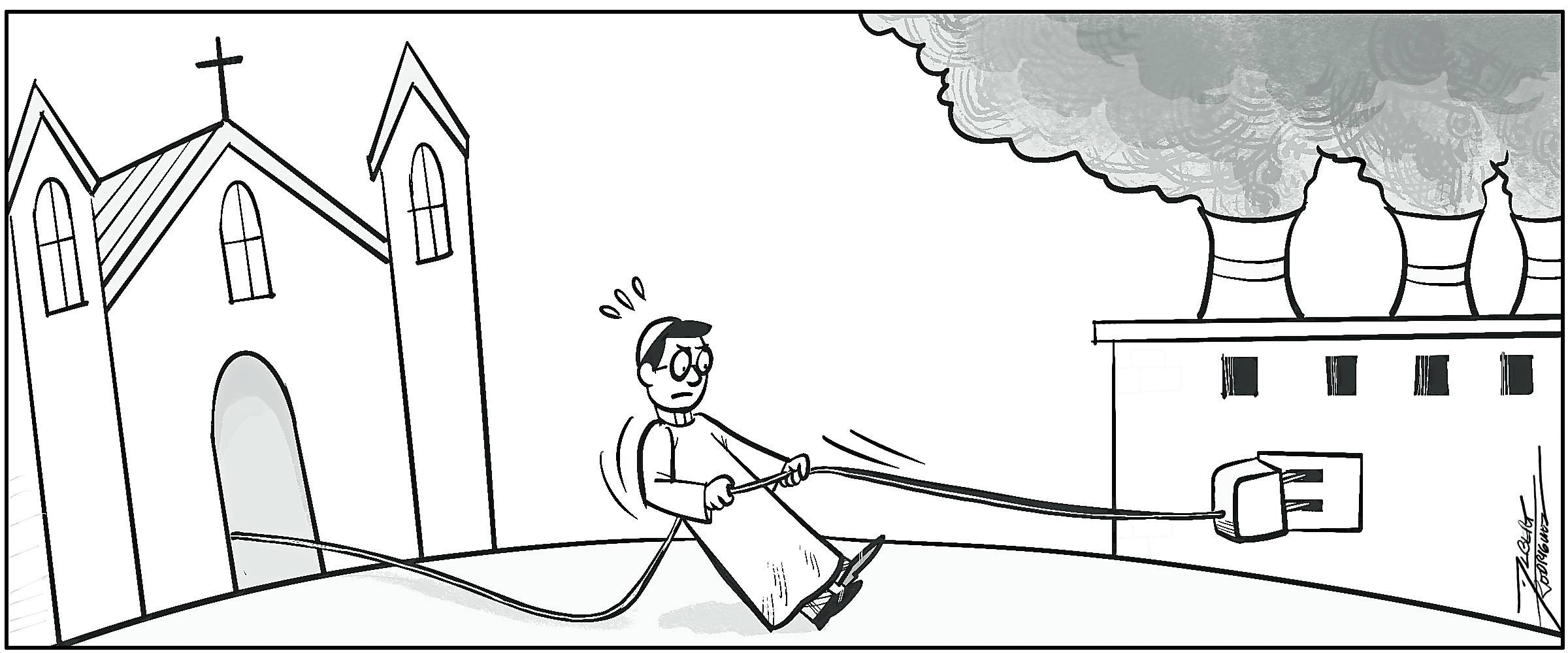

Article continues after this advertisementJust last week, however, the plenary assembly of the Catholic Bishops’ Conference of the Philippines (CBCP) adopted a stance that would surely prove controversial and perhaps even put in peril the Church’s financial security. The bishops, headed by CBCP President Bishop Pablo Virgilio David, decided that henceforth local churches would no longer accept donations from enterprises that are “destructive” to the environment, such as fossil fuel production, mining, and logging. The CBCP statement also urged Church organizations to withdraw, “not later than 2025,” Church resources from banks and other financial institutions “without clear commitments… to divest from fossil fuels.”

Among the goals articulated in the CBCP statement are “to disable the coal industry,” as it described coal as “the dirtiest of all fossil fuels;” establish a timeline for reducing reliance on fossil fuels; reject nuclear power, and set “ambitious” targets for renewable energy development and efficiency by 2050.

As the struggle to undo decades of environmental abuse and exploitation rages, the bishops said they are “saddened that many of our faithful and partners taking peaceful actions toward ecological conversion are also experiencing increasing harassment and violence.”

The policy adopted by the CBCP, the bishops said, was in line with a 2019 pastoral letter encouraging divestment from industries destructive of the environment, and with Pope Francis’ 2015 encyclical “Laudato Si’, Mi’ Signore” (Praise Be to You, My Lord), which called on the faithful to “Care for Our Common Home.”

Facing the media, Bishop David urged the faithful, especially parish priests, to be “very critical,” urging them to study the sources of their funding so that those providing donations are not engaged in enterprises that are “destructive to our environment, that is very contradictory to our mission.” For their part, the bishops said they would form institutions and task groups to study the links between industries and global warming, and lead the way in reducing the carbon footprint of schools, institutions, and offices associated with the Church while defending laypeople who find themselves threatened by armed groups, including the military or police, for their work on behalf of the environment.

While a powerful institution, the Church cannot do this alone. It’s about time then for Catholic Filipinos to join the fight to save our Mother Earth and thereby secure our common future.