Racking up debts

It’s bad enough that Filipinos are saddled with a national debt that had risen to record highs ostensibly to help the Philippines recover from the devastation wrought by the lingering COVID-19 pandemic.

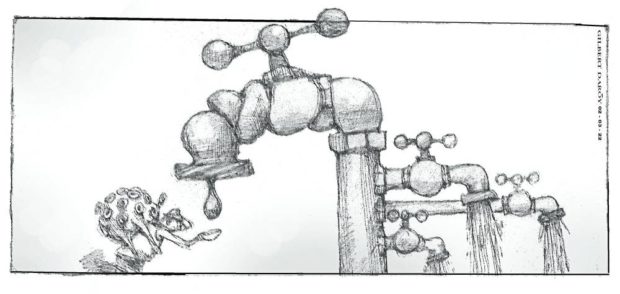

But what’s making the burden more difficult to bear is the growing likelihood that a part of the borrowings may have been lost to corruption, based on the Senate blue ribbon committee’s report on the questionable P11.5 billion worth of contracts for pandemic supplies won by Pharmally Pharmaceutical Corp. in 2020 and 2021.

And those are just the contracts that fortunately caught the attention of the Commission on Audit.

How about the rest that had been awarded since March 2020 when the COVID-19 pandemic first hit the Philippines and subsequently triggered unprecedented public health and economic crises from which the Philippines is still struggling to recover?

While the extent of the corruption behind the COVID-19-related contracts is a matter of speculation at this point, what is certain is that the Philippines continues to rack up a debt bill that is in danger of going beyond the point that credit rating agencies consider sustainable or manageable.

ING Bank Manila senior economist Nicholas Mapa said last year that it was “quite clear that debt watchers are now increasingly concerned about the medium-term growth prospects for the Philippines, suggesting that the so-called ‘solid fundamentals’ are now being questioned.”

The Department of Finance reported that as of Jan. 14 this year, total foreign borrowings and grants devoted to COVID-19 response from March 2020 has reached $25.79 billion or P1.32 trillion.

This includes the $1.2 billion it borrowed from the World Bank, the ADB, and the China-led Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank in March 2021 to buy vaccines, plus another $800 million from the same three development banks in December to purchase booster and pediatric shots.

With the country still firmly in the stubborn pandemic’s grip, especially with the most recent surge in cases caused by the Omicron variant that brought with it a fresh round of mobility restrictions, more will definitely be added to the tally.

Only recently, the government already said it would borrow another $400 million from the World Bank to support “policy reforms” for sustainable recovery from the pandemic. At the end of 2021, the Bureau of the Treasury said the country’s outstanding debt already reached P11.73 trillion, 19.7 percent more than the 2020 level. This puts the ratio of debt to gross domestic product or total domestic economic output at 60.5 percent, the highest in 16 years and also the first time it returned to the 60-percent level since 2005.

If the ratio will stay above the 60 percent level and the rating agencies conclude that it is unsustainable—Fitch’s outlook on the Philippines already deteriorated to negative from stable—then a downgrade of the Philippines’ sovereign rating may not be far behind and that means it will become more expensive for the Philippines to borrow money to finance needed programs including infrastructure development.

The Duterte administration’s economic managers have long argued, however, that the rising debt level was not just manageable but necessary for the country to ably respond to the challenges brought about by the pandemic and put it in a position to rebound from the unprecedented crises it has spawned.

As the economic team rightly pointed out, other countries in the region have likewise taken on more debt than usual because of the pandemic. However, while the economies of neighboring countries are firmly on their way back to their pre-pandemic vigor, the Philippines is expected to bring up the rear. It has likewise earned the unwanted distinction of being the most vulnerable to COVID-19 among 56 advanced and emerging markets covered by the January 2022 scorecard of UK-based think tank Oxford Economics. The Philippines was likewise once again ranked the worst in COVID-19 resilience among 53 countries evaluated by Bloomberg, the third time it was named the cellar dweller in just the last five months, raising burning questions over the soundness of the programs that these borrowings are supposed to be for. “Difficulties administering vaccines in remote areas continue to be a vulnerability as the country sees an Omicron surge worse than other Southeast Asian countries like Malaysia, Indonesia and Thailand,” Bloomberg said in its latest report.

Fortunately, the worst of the Omicron surge seems to be over, but the debt burden is here to stay and, as Finance Secretary Carlos Dominguez III said, a major issue that the next Philippine president will have to address if the Philippine economy is to return to the pink of health.

But more than arguing over the wisdom of taking on more debt, what is more important for pandemic-weary Filipinos is the reassurance that the debt that they will eventually pay for goes to effective pandemic response strategies and will not end up bankrolling failed programs or worse, lining the pockets of unscrupulous government officials and their cohorts.