Unforgettable was that time at the start of the pandemic in March 2020 when the government abruptly announced a lockdown in Metro Manila, resulting in untold numbers of people milling in the streets, unable to get to their workplaces, and taxi drivers, among others, bewildered at being pulled over and threatened with arrest by cops, unaware that an order had come down banning public transport operations.

In the tumult two figures stood out, their images capturing the grim ironies of life in these parts—an irate “influencer” demanding to know what these “motherf*ckers” were doing outdoors and an elderly cabbie near tears and wondering how else he and his fellows could get by with work getting harder by the day.

The influencer, apparently apprised of her ignorance of how the majority lives, later apologized to those she had insulted (not that it mattered in the long run); the cabbie doubtless went on lamenting his fate. But in the course of the lengthy ban on public transport imposed by the task force that to this day holds the lives of millions of Filipinos in its hands, drivers of public utility vehicles were driven to penury and to literally beg for crumbs in the streets. Many of them have yet to fully recover from that terrible time.

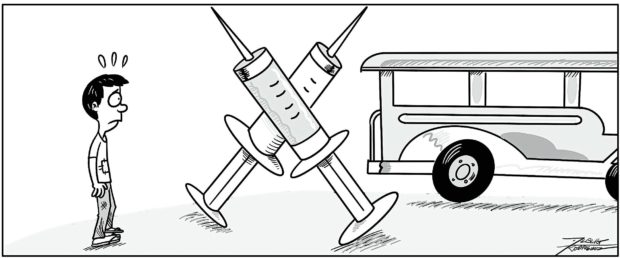

On Jan. 17, on the eve of yet another oil price increase, one more threat to their livelihood was dealt by the Department of Transportation (DOTr) through its “no vax, no ride” policy that only those fully inoculated against COVID-19 will be allowed access to all modes of public transport in Metro Manila. The policy directly impacts not only members of the low-income class who have no vehicles of their own but also the drivers/owners of the public utility vehicles they patronize; it directly ignores Section 12 of Republic Act No. 11525 (the COVID-19 Vaccination Program Act) stating that a vaccination card is not a requirement for educational, employment, and government-transaction purposes.

Many Filipinos refuse to be jabbed for personal, medical, and other reasons, including the not unfounded idea that COVID-19 vaccines are being used for emergency purposes and carry certain fatal risks no matter how small (the waiver that prospective vaccine recipients are required to sign before they are jabbed proves this). They are fearful of the effects of a COVID-19 vaccine on their physical constitution and claim (correctly) that it is their own body at stake—but they forget that other bodies are at stake as well.

Physicians will agree that vaccinated (and boostered) and unvaccinated persons are equally capable of being infected by the virus and passing it on to others. It is thus not an exaggeration to say that the “no vax, no ride” policy is discriminatory to the unvaccinated poor who have no means to get to their workplaces or do their errands, even if they have to get up at the crack of dawn to take their place in a winding queue of commuters. In their private vehicles, the unvaccinated wealthy do not have to put up with any such aggravation (although they now have to contend with restrictions).

The government is not lacking in suggestions from a concerned public in addressing vaccine hesitancy. But its approach is, as always, more coercive than compassionate, more harsh than helpful. It could be better spending its energies mounting information campaigns in several languages on the virtues of vaccination for vulnerable sectors, or strengthening public testing along with the overall public health system. But already it has warned about fines and other penalties to be imposed on the unvaccinated venturing out of their homes, and on drivers of jeepneys allowing them on board. The DOTr’s idea of deploying secret enforcers or “mystery passengers” to ensure that drivers and passengers are complying with its policy is another hairy provocation.

Having been assigned near-criminal status, however, the unvaccinated may be finding it even more difficult to get to a jab center even with the exemption it offers from the “no vax, no ride” policy. (The warm bodies crowding such centers are said to be pushing the surge in infections—a classic Catch-22 situation.)

Senate President Vicente Sotto III suggests the designation of specific spaces in trains and buses for the unvaccinated, pointing out that there are “other ways to fight the pandemic” than “destabilizing” the people’s means of transport. Indeed there are, if the government would for a moment drop its militarist mindset.

Exasperation with the government’s discriminatory policy drove “Diane,” an employee who was barred from taking the bus as she was only partially vaccinated (her second dose is set for February), to tears. Her lament, as reported in 24 Oras newscast, says it for all: “Nakakapagod yung ginagawa nila … Napagod na ako, Diyos ko.’’