A virus, not a vaccine

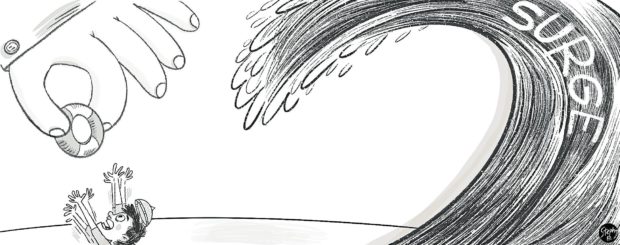

With COVID-19 cases in Metro Manila surging to a new record high since the pandemic began in 2020 — at least 28,707 cases as of Sunday — people are desperately clinging to any assurance that the end to this crippling health crisis is in sight.

This might explain why a statement on the Omicron variant of the virus, describing it as the “beginning of the end of the pandemic,” immediately gained traction, no matter how presumptive and irresponsible the claim is, according to health experts.

On Jan. 5, OCTA Research fellow Fr. Nicanor Austriaco issued a controversial statement on the variant in a Go Negosyo Forum.

“We have to realize that Omicron is the beginning of the end of the pandemic because Omicron is going to provide the kind of population immunity that should stabilize our societies and allow us to reopen,” he declared. Omicron, Austriaco said, will be a “natural vaccine’’ that can provide the population with antibodies that will protect them from all COVID-19 variants.

“This is the hope and the prayer. The Omicron is actually a blessing. It will be hard for one month, but afterwards, it should be a blessing because it should provide the population protection that we need everywhere,” he added.

Thankfully, other health experts immediately debunked Austriaco’s fantastical statement to stem the damage it might have caused an unsuspecting public.

In a Palace press briefing, Health Undersecretary and spokesperson Maria Rosario Vergeire warned the public against willingly getting themselves infected with the Omicron variant because of Austriaco’s statement.

“The higher the infections, the higher the chance of the virus to replicate — which is their cycle — and they can reproduce,’’ Vergeire added.

“The Omicron is a virus, not a vaccine,” succinctly stated Dr. Edsel Salvana, a member of the Department of Health (DOH) Technical Advisory Group (TAG) and director of the Institute of Molecular Biology and Biotechnology at the National Institutes of Health at the University of the Philippines-Manila.

Even Austriaco’s fellow at OCTA, Dr. Guido David, distanced the group from the claim. “Not a statement by OCTA. He is sharing his perspective. It is not my perspective or that of OCTA,’’ David said in a tweet.

While it is commendable for the DOH and OCTA Research to clarify Austriaco’s alarming statement that could set up unrealistic expectations and encourage complacency among a pandemic-weary populace, it is high time for the government to take a more proactive stance since the virus keeps mutating. Though the global health crisis is now entering its third year, herd immunity is far from being achieved in the country, and citizens are still left on their own to cope with the difficulties of being infected.

Take the need for self-administered COVID-19 antigen test kits which became more pronounced as the surge in infections overwhelmed public and private testing laboratories, with results released three or four days later instead of the customary 24 to 48 hours. Unable to access this more affordable testing option, asymptomatic individuals could unwittingly be transmitting the virus, while the undue delay in the release of results could affect the recovery prospects of those infected.

More than two years into the pandemic and antigen test kits for home use have yet to be registered with the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) despite their availability from online sources. Couldn’t the FDA and the DOH have taken their cue early on from other countries which made these test kits available to the public—some for free—and facilitated registration of these test kits instead of just waiting for importers to apply?

Then there’s the current shortage in paracetamol attributed to a spike in demand, as people experiencing flu-like symptoms resort to self-medication in the absence of more accessible testing means. Some pharmacies had to import the medication to meet local demand as the government seems unable to control possible hoarding among consumers.

More disappointingly, the government has yet to achieve its vaccination target despite the availability of COVID-19 vaccines in storage facilities around the country. Instead of threatening sanctions including arrest for those who refuse to be jabbed, why not offer incentives to encourage anti-vaxxers to get their shots? A more concerted barangay-level information drive could also go a long way to shatter misconceptions about the risks and effects of the vaccine that may still be prevalent especially in remote areas.

Seeing the government exhaust all means to protect Filipinos from the virus would be a real blessing—and an assurance that people won’t fall prey to such dangerous notions as Omicron being the “blessing” we’ve all been waiting for.