Build ‘coastal greenbelts’

Siargao became known to the world for its surfing sites but, in the aftermath of Supertyphoon Odette, another feature of the island is getting the spotlight: its mangroves, which have been credited with helping protect adjacent communities from the severest impact of the storm.

According to reports from those who survived the destruction that Odette brought to the Visayas and Mindanao regions several days before Christmas, Siargao’s mangrove forests protected residents from a storm surge headed toward Del Carmen, one of the nine municipalities in the island. The municipality boasts of the largest mangrove forest in the Philippines, covering 4,871 hectares. Siargao is also the largest protected area under the National Integrated Protected Area System Act due to its 8,620-hectare mangrove forest.

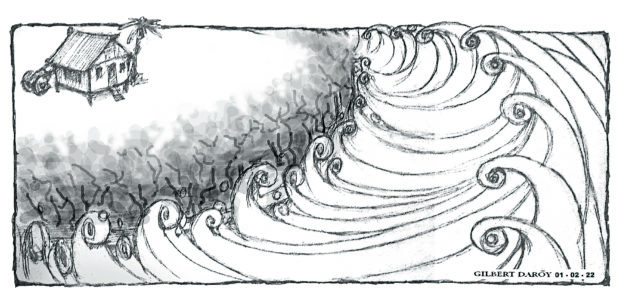

Article continues after this advertisementMangroves, which serve as a natural coastal defense against violent storm surges and floods, can protect communities from sea-level rises and severe weather events caused by climate change, because they can absorb or reduce wave energy by up to 60 percent. These mangroves are especially crucial for a country like the Philippines where 60 percent of the population live in coastal areas.

In 2013, Barangay Parina in Giporlos, Eastern Samar, was saved by its mangroves from the storm surge generated by Supertyphoon Yolanda. Two large mangrove forests about nine hectares in size that sandwich the barangay served as its protective cover when water surged inland.

On the other hand, Bacjao, another barangay nearby but located outside the mangrove area, was completely destroyed when the storm surge swamped the village, according to an Inquirer report in November 2014. A local official recounted back then that the rush of water in Parina was not strong and slowly receded within five to 10 minutes, while the flooding in Bacjao destroyed even those houses built with sturdier materials.

Article continues after this advertisementYolanda, however, also wreaked havoc on the mangrove forest in Eastern Samar. Only 30 percent remained intact after the storm, and the forest had to be rehabilitated and maintained. It is not the only mangrove area in the country that has faced degradation or outright destruction. The United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction had noted that many of the Philippines’ mangrove ecosystems “are severely degraded and efforts to restore them often fail.”

In April 2015, it was reported that efforts to rehabilitate mangroves after Yolanda only wasted government funds because the wrong species were planted and even the process of identifying the locations where the program was to be implemented was riddled with corruption, such as attempts to bloat the coverage area to justify bigger budgets.

Extreme storms like Odette and Yolanda highlight the need for building what Mindanao marine scientist Jurgenne Primavera calls “coastal greenbelts.” Primavera, recognized by Time magazine as a “Hero of the Environment” in 2008 for her work on mangrove ecosystem conservation, has called for legislation that would create a belt of mangrove forests across the Philippines to protect coastal communities from severe disasters. This undertaking is even more urgent since—as the World Economic Forum warned in 2019—over a third of the world’s mangroves have disappeared, and they are being cleared faster than tropical rainforests due to land reclamation for agriculture, industrial development, and infrastructure projects.

Not many know that there are mangroves in the country’s capital, but the little patches that are left in Manila Bay have been chronically choking in plastic pollution. Experts from the UP Diliman Institute of Biology offered to help the government last year implement a science-based rehabilitation program for the polluted bay that would include replanting mangroves along the coast. Instead, the government opted to spend millions on its controversial dolomite beach, which it needs to top up regularly because of erosion especially during typhoons.

“We have to move from disaster response to resilience, specifically coastal resilience … for a country yearly blighted by 20 storms which make landfall where the sea meets the sand, meaning on the beach lining most of our 36,300-km long coastlines,” Primavera appealed on Facebook last Dec. 23. Several bills have been filed in Congress since 2016 to establish such a “national coastal greenbelt,” but the proposals have yet to prosper.

In her Facebook post, Primavera also shared several photos showing the devastation that Odette wrought on coastal communities, noting how they could have been saved, or would have sustained minimal damage, had they been covered by mangroves and beach forest trees.

“We needed them decades ago,” Primavera said of this natural coastal protection. Continued inattention by the government, she warned, means “hundreds more die with each typhoon.”