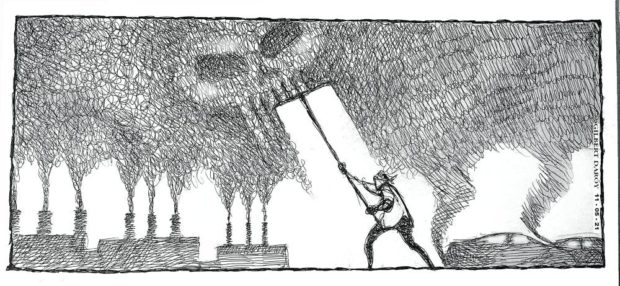

Killer air

A week into the initial COVID-19 lockdown in March last year, residents of Metro Manila, the country’s economic hub, looked out of their windows and saw clear, blue skies and pronounced skylines they hadn’t seen in decades. With people locked inside their homes after public and private vehicles were banned from the roads, and business operations such as factories and construction activities halted, the metropolis’ notoriously noxious air cleared for once.

But it wasn’t for long, because as soon as restrictions were partially lifted in May 2020, the polluted air returned. A recent report corroborates what experts have been warning for decades: Air pollution is a silent killer, and the impact on the Philippines has been grim.

Article continues after this advertisementPer the report “Aiming Higher: Benchmarking the Philippine Clean Air Act,” approximately 66,000 premature deaths every year in the Filipino populace are linked to PM2.5 and NO2 pollution (defined below) in the country. The report launched this week by the Center for Research on Energy and Clean Air (Crea) and the Institute for Climate and Sustainable Cities estimated the economic cost, meanwhile, at $87.6 billion (P4.5 trillion) annually — 23 percent of the country’s GDP in 2019—as a result of air pollution-related health illnesses, disabilities, and even death.

The breakdown of the estimated economic loss caused by air pollution is as alarming as the Pharmally billions: P24.7 billion from work absences; P21.6 billion from childhood asthma; P90 million from emergency room visits due to asthma episodes among adults and children; P53 billion from years lived with disabilities arising from diabetes, chronic respiratory diseases, and stroke, which significantly lower the quality of life and economic productivity of people affected and cause substantial health care costs; P29 billion from preterm births as a result of additional maternal and neonatal care; P4.43 trillion from cases of premature deaths or deaths that could have been avoided with better air quality.

“The growing scientific understanding that air pollution is more dangerous to human health than originally estimated, and the widened gap between the World Health Organization’s ‘safe levels’ of air quality in 2021 and the Philippine National Ambient Air Quality Guideline Values (NAAQGV), means that allowable concentrations for pollutants are almost 5 times higher than recommended for the full protection of Filipinos’ health,” the report stated.

Article continues after this advertisementThe WHO’s annual recommended limit (updated last September) for PM2.5, or fine particulate matter that are 2.5 micrometers or smaller in diameter, is 5 micrograms per cubic meter (μg/m3); while that for NO2 or nitrogen dioxide is 10 μg/m3. Examples of PM2.5 are those that come from vehicles, construction equipment, exhausts, dust, etc. — so small that they easily pass through the throat and nose and enter the lungs, causing respiratory diseases. Last year, the Philippines’ PM2.5 went down to an average of 14.78 μg/m3 from 17.6 μg/m3 in 2019, the decrease mainly due to the COVID-19 restrictions. But even so, this was still above the WHO’s previously recommended level of 10 μg/m3 set in 2005. In addition, data from a Crea and Greenpeace report released in June last year showed a nasty rebound—a 75-percent jump in NO2 levels in Pasig and Makati within a week after restrictions were eased in May 2020.

Needless to say, in a lingering pandemic where the population has to constantly protect itself from an airborne disease, maintaining air quality is critical to make people less vulnerable to COVID-19 and other respiratory illnesses.

To address the problem of air quality on a long-term basis would entail a review of the Philippines’ NAAQGV so they could be consistent with the WHO’s newest recommendations, the Crea report stressed. This would also require an update and more efficient implementation of Republic Act No. 8749 or the Clean Air Act, enacted in 1999. The law mandates, among others, that the Environmental Management Bureau review the NAAQGVs every year—a time- and resource-consuming task that may need to be revisited, since other countries like the US, Indonesia, and China review theirs every five years. The report also identified other issues such as lax emission standards and very low penalties imposed on polluting facilities; and inconsistent data collection mainly due to lack of equipment.

Still, the threat of killer air (it causes seven million premature deaths globally a year, according to WHO) requires more than merely adjusting NAAQGVs, because what is the point of increasing the standards without taking a look at related issues in urban planning, transport, industry, infrastructure, population distribution, etc.? Here, in other words, is another urgent, extraordinarily tangled social problem the next administration will have to wrestle with.