It is so difficult being an Ampatuan these days,” lamented a woman community leader a few years after the arrest and detention of her relatives in connection with what has become known as the Maguindanao massacre of 2009.

The case, in which 58 people were killed, including 32 media workers, had earned front-page headlines and the lead spot in radio-TV and online news for days, weeks, and months. Two years ago, about 10 years after their trial began, the most prominent of the accused were found guilty by Quezon City Judge Jocelyn Solis-Reyes. The alleged mastermind behind the massacre, former Maguindanao governor Andal Ampatuan Sr., died behind bars in 2015 due to illness. But his sons—Zaldy Ampatuan, former governor of the defunct Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao; Andal “Datu Unsay” Ampatuan Jr., former mayor of Datu Unsay town; and Anwar Ampatuan, former mayor of Shariff Aguak town—were still around to serve the sentence.

In all, 28 defendants, some of them police personnel, were found guilty and ordered to indemnify the survivors of the victims. But more than a hundred other accused were either acquitted, or went missing and 75 are still at large today. Indeed, the case is still far from settled, haunting the families of the deceased and casting a shadow over the people of Maguindanao and over all journalists in the country.

The Maguindanao massacre, after all, has been deemed the worst election-related incident of violence in the country and the deadliest attack on the working press in the world.

But, no, the lamenting woman member of the Ampatuan clan was wrong. It is not so difficult, it seems, to belong to her still-powerful family network these days. Proof is the “raised-arm” photo of presidential candidate Sen. Manny Pacquiao and Yasser Ampatuan, who is running for governor of Maguindanao province. A witness has placed Ampatuan at the dinner in 2009 where the candidacy of Esmael “Toto” Mangudadatu for governor was allegedly discussed and the decision to mount an operation to stop him was made.

And to add drama to the tableau, Yasser is running for governor against none other than the original target of the assassination attempt: Mangudadatu, who lost his wife and sister in the ambush-massacre of 2009 along with a number of woman relatives and media members. He had hoped, mistakenly it turns out, that the party of women relatives and media would be left alone to file his certificate of candidacy in accordance with Muslim tradition and in fear of the media’s “power.”

No wonder the families orphaned by the heinous killings have yet to, in the reprehensible language of historical deniers, “move on.” Members of one family in particular have said they cannot forgive or forget. They are the loved ones of Bebot Momay, a photojournalist of the Midland Review based in Tacurong City, Sultan Kudarat. He was almost certainly part of the motorcade, since his identification card was found among the debris in the site. But his remains have yet to be found, and he continues to be listed as “missing” in official records.

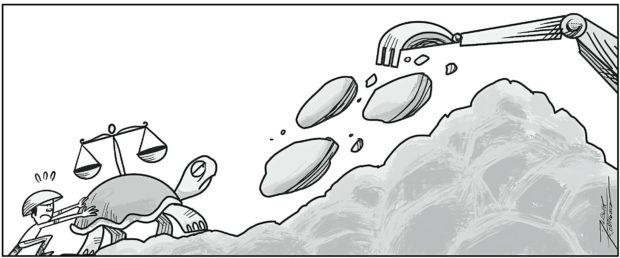

The families and their lawyers are concerned over the continuous appeals that the convicted and accused have filed before the courts. Jonathan de Santos, chair of the National Union of Journalists of the Philippines, has warned that continuing vigilance is needed since the appeals may still produce developments favorable to the defendants. Ivy Orina, whose brother Jephon Cadagdagan was among those killed, voiced out the grief and frustration of those still waiting for justice: “It has been 12 years already and we still have not seen justice. If the accused keep on appealing, what are we to do?”

The fate of the journalists who took part in the Mangudadatu motorcade is also a lingering specter for members of the press struggling in the present atmosphere of intimidation and confrontation against media critics. More media workers have been killed during the almost six years of the Duterte administration than in any other administration (yes, including during the Marcos dictatorship). Couple this with the “weaponizing” of the law on libel/cyberlibel and of regulations on the ownership of the media, the most prominent of which were trained on the online media outfit Rappler and broadcasting giant ABS-CBN, and you effectively have some media members who are forced to be wary, cowed, controlled, and silenced, to the detriment of the public welfare and the nation’s already much-bruised democracy.