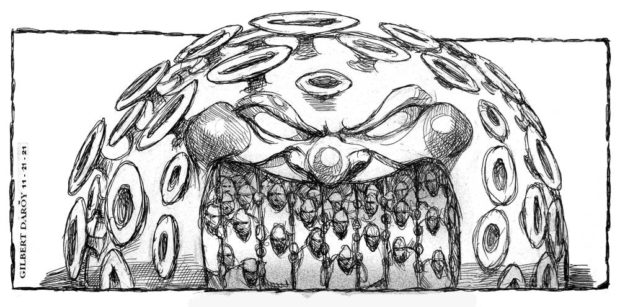

Editorial cartoon

Philippine jails are among the most overcrowded in the world. So, imagine the situation under this pandemic, which requires avoiding the three Cs: closed spaces, crowded places, and close-contact settings—all impossible in the country’s hellishly congested prisons.

Worsening the situation is the fact that only a fraction of the country’s inmates in the jails and penal facilities have been vaccinated against COVID-19, making them extremely vulnerable to the virus.

Two months ago, Kapatid, an advocacy group for political prisoners, already called on the government to allocate more vaccines for persons deprived of liberty (PDLs), citing that only a few of them have received their jabs. This was based on the annual audit report released last August where the Commission on Audit noted the low vaccination rate in facilities managed by the Bureau of Jail Management and Penology (BJMP) and the Bureau of Corrections (BuCor).

As of August, BJMP had vaccinated only 10,939 of its inmates—barely even 10 percent of its 119,692 PDLs, while BuCor had vaccinated only a little over 5 percent or 2,684 of about 48,000 convicts in its facilities. Just this week, or three months later, reports bared that only 4,173—not even 10 percent of the total PDLs in BuCor’s facilities—have already received their vaccine shots.

As of Nov. 9, there has been little improvement in the vaccination numbers. BuCor, which takes charge of the seven national jail and penal facilities under the Department of Justice, reported that only 10 of the more than 28,000 PDLs at the New Bilibid Prison (NBP) in Muntinlupa City have received their COVID-19 vaccines, while NONE of the 17,329 convicts at the NBP’s maximum security compound has been inoculated.

“What happened to [DOJ Secretary Menardo Guevarra’s] statement that his office will seek the inclusion of PDLs from the Bureau of Corrections and the [Bureau of Jail Management and Penology] in the government’s list for vaccination?” Kapatid spokesperson Fides Lim asked in September. She said the government should include the PDLs’ prompt vaccination and “directly allocate financial resources for their immunization instead of engaging in a policy spree of arrests, including politically motivated arrests, which only worsen jail congestion.”

The Commission on Human Rights (CHR) also reminded the government of its humane duty to uphold the right to health of PDLs detained in jails in the country. “CHR recalls that under Mandela Rules, all PDLs must enjoy health care with similar standards to those available in the community and should have access to necessary health-care services free of charge and without discrimination,” it said in a statement.

On top of the slow vaccination rate, the current population at BJMP’s facilities far exceed the ideal capacity of 34,893 inmates — by a staggering 403 percent. Per the COA, this is “way beyond the accepted standards” of the United Nations. The congestion rate was based on the 115,336 inmates in BJMP facilities as of end-2020, but the number has since increased by at least 4,000 as of August, which means it is even more cramped now—a scary situation where COVID-19 is concerned.

To decongest the crowded jails, authorities released more than 81,000 inmates from March to October last year. In June 2020, reports said more than 700 PDLs had contracted the virus, while 21 had died from it including nine high-profile PDLs (one of them Jaybee Sebastian, a drug convict and state witness in the case against Sen. Leila de Lima).

A paper published by the Oxford University Press in December last year, “Philippine prisons and ‘extreme vulnerability’ during COVID-19,” called the country’s inmates and detainees as the “hidden victims of the COVID-19 pandemic,” given their “locked away” situation as well as the shortage of resources and non-compliance with minimum health standards inside the facilities. “What the pandemic uncovers—even in prisons—is the ‘existence of underlying unfair social and economic structures that are tightly bound to unfair health outcomes,’” it said.

The response to the pandemic in prisons and other detention places, according to the World Health Organization, requires a whole-of-society approach, noting that efforts to control the spread of the virus are likely to fail if prevention and control measures, testing, treatment, and care are not carried out in these places. “Prison health is part of public health so that nobody is left behind,” it said.

The wheels of justice may grind exceedingly slowly for many of these PDLs, but the rollout of vaccines for them should not be as glacially paced, now that the government has revved up its inoculation program.