Dismal investment record

Despite having a highly-skilled, English-speaking workforce, a favorable geographical location in a region that has seen the fastest growth rates in the world, and efforts to improve the ease of doing business in the country, the Philippines still placed second to last among 14 Asia-Pacific economies in terms of attractiveness to foreign direct investments (FDIs), as ranked by the UK-based think tank Oxford Economics.

In the latest FDI attractiveness scorecard released last Oct. 11, the Philippines was ahead only of Taiwan. In first place was China, followed by Vietnam. Oxford Economics cited only the country’s weak infrastructure and competitiveness for the low inflow of FDIs. The Philippines scored poorly in infrastructure and business environment, with Oxford Economics specifically citing the latest Global Competitiveness Report where the Philippines ranked 92nd out of 140 countries in infrastructure quality.

The Philippines, together with Indonesia, also scored poorly in terms of ease of doing business. “According to the World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business Report 2020, they are both ranked 70 or above out of 190 countries, comparing unfavorably to the advanced Asian economies and several of their regional peers,” said Oxford Economics.

The numbers support this assessment. Data released by the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas showed that the Philippines received $7.93 billion in FDIs in 2016. This rose to $10 billion in 2017, then fell to $9.8 billion the following year. This declined again in 2019 to $8.67 billion and, with the economic recession caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, FDI inflows to the Philippines shrank to $6.54 billion in 2020, the lowest since 2015. For the first half of 2021, FDIs grew by 40.7 percent to $4.3 billion.

For perspective, the Asean Investment Report 2020-2021 released last September said FDIs into the Association of Southeast Asian Nations amounted to $137 billion in 2020, of which the Philippines attracted only $6.54 billion. The year before, the amount was at an all-time high of $182 billion, of which the Philippines got only $8.67 billion. The three biggest recipients were Singapore with $114.2 billion in 2019 and $90.6 billion in 2020; Indonesia, $23.9 billion and $18.6 billion; and Vietnam, $16.1 billion and $15.8 billion.

Other factors may figure into why foreign investors are anxious about investing in the Philippines. After winning the 2016 elections, then President-elect Rodrigo Duterte sought to calm the business community’s fears about his blunt style of governance by laying out an eight-point economic plan to sustain the country’s growth. One of these was to attract more foreign investors by stamping out corruption to improve the ease of doing business, lifting restrictions on foreign ownership in certain economic sectors, and joining regional trade blocs.

More than five years later and less than a year before the end of the Duterte administration, however, the level of FDIs has remained dismally low despite measures to help attract foreign investments, including the passage of laws on fostering ease of doing business and cutting corporate income tax rates.

A big stumbling block appears to be the government’s failure to open more economic sectors to foreign ownership. In 2016, the Asian Development Bank (ADB) already noted that the decision of foreign investors to put money in a particular area depended to a great extent on the investment policy regime and domestic regulations of the host economy.

“Domestic regulations in many economies — including the People’s Republic of China, India, and the Philippines — limit foreign ownership in various industries to joint ventures, therefore erecting high barriers for greenfield FDI,” the ADB said.

While Congress had shown some interest by approving bills to relax the Foreign Investments Act, the Retail Trade Liberalization Act, and the Public Service Act to open more sectors to foreign ownership, none has been passed into law.

Another major hurdle dampening foreign investor interest was pointed out by former economic planning secretary Cielito Habito in his Sept. 14, 2021 column in this paper: the bad state of governance in the country. “When dealing with government from the top leadership down to local governments is — to put it kindly — fraught with risk and uncertainty, a potential foreign investor would simply move on and look elsewhere in the neighborhood,” wrote Habito.

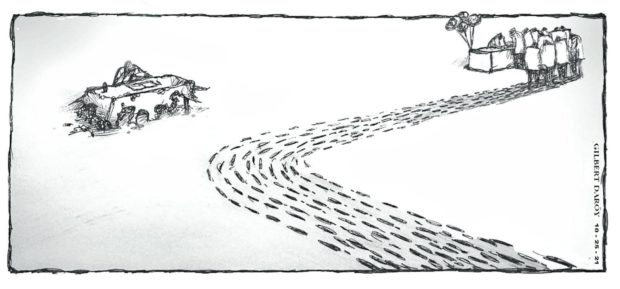

The Asean neighborhood has indeed reaped much of what the Philippines has failed to attract and develop; over five years of the Duterte administration’s efforts have not been enough to swing the tide the country’s way. The next administration to take over in 2022 has a paramount economic task: Prioritize measures to resolve all such impediments and issues if it is to succeed in luring in more foreign investments and lifting the country out of its laggard status in the region.