So President Duterte has signed into law a new tax on Philippine offshore gaming operators (Pogos). Big deal. Are Filipinos afflicted by the economic and other effects of the COVID-19 pandemic heartened, even if, as Republic Act No. 11590 states, 60 percent of the revenues to be derived will fund the Universal Health Care Act, the health facilities enhancement program of the Department of Health (DOH), and the fulfillment of Sustainable Development Goals as determined by the National Economic and Development Authority? Shocking details are emerging from the Senate blue ribbon inquiry into how the undercapitalized Pharmally Pharmaceutical Corp. has benefited from the DOH transfer of P42 billion in taxpayer money to the Procurement Service of the Department of Budget and Management. It’s likely that news on the new Pogo tax law is coming across as mere yada yada.

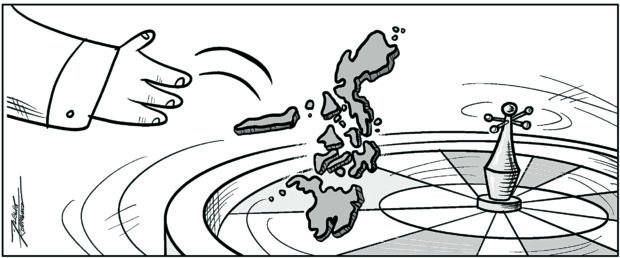

For one, the law comes too late, a big number of the mostly Chinese-run Pogos having flown the coop. For another, it’s perceived as too soft on the enterprises that, although banned in China, had flourished in this country under the tender ministrations of the Philippine Amusement and Gaming Corp. (Pagcor). Senate Minority Leader Franklin Drilon and Senators Risa Hontiveros and Francis Pangilinan voted against the passage of the tax bill as it stood. And apart from initiating inquiries into the crimes that arose alongside the Pogos (bribery, prostitution, and kidnapping, among others), Hontiveros has asked the crucial question: “Why were debts by Pogos allowed to get this big?”

The Bureau of Internal Revenue has long admitted the Pogos’ tax delinquency. The Commission on Audit reported that as of Dec. 31, 2020, Pagcor had P1.382 billion in overdue receivables; of that amount, P1.365 billion was owed by 15 Pogos, only three of which were still operating as of Jan. 12. That’s on top of the privileged bubble created for Chinese Pogo workers, which allows them to thumb their noses at even the rules governing homeowners’ associations.

“Pagcor needs to go after them,” Hontiveros said, correctly. “Not only do they owe more than a billion, they have also brought in crime. Pogos, pay your dues and get out of the Philippines.”

Not that it would be easy to root out these gambling enterprises that brought sleaze and crime but also windfalls to the property, restaurant, and related sectors. It’s said that at their peak, Pogos were bringing in an estimated P551 billion in annual revenues, enriching the gambling culture in place. Recently Mr. Duterte turned around from his “I hate gambling” stance of 2018 and approved the resumption of casino operations on world-famous Boracay in Malay, Aklan, ostensibly because his administration needed money and would get it even from gambling. Per Pagcor chair Andrea Domingo, this meant the green light for two pending casino projects under the aegis of Andrew Tan’s Megaworld and the Macau-based Galaxy Entertainment Group.

Here in stark terms are the two faces of development in a Third World country where poverty flourishes and the work of regulatory agencies are patchy at best. She needed prodding to reply categorically, but Tourism Secretary Bernadette Romulo Puyat is not fighting the lifting of the ban on casinos on one of the Philippines’ top tourist destinations — a position also taken by the Boracay Inter-Agency Task Force, which manages the island’s rehabilitation. It wasn’t too long ago when Puyat’s Department of Tourism, along with the Department of Environment and Natural Resources, firmly backed the ban, the better to safeguard Boracay’s carrying capacity and its selling point as a family-oriented destination.

Of course, it’s true that Boracay residents dependent on tourism are gripping the knife’s edge. Malay Mayor Frolibar Bautista was heard saying that the townsfolk, having grappled with financial difficulties brought by the pandemic-induced slump in tourism, should keep an open mind. He cited an existing management system, as well as the 5-percent cut off Pagcor’s income from casino operations that the local government would supposedly receive.

But the group Natives of Boracay and Business Stakeholders Inc. is “extremely dismayed and disappointed” at the President’s move, and has urged the government to address the island’s major concerns — overcrowding, solid waste management, sewerage, and stable water and power supply—“before allowing more developments to sprout on [it].”

On Saturday a protest caravan wended its way from the capital town of Kalibo to Malay to dramatize the residents’ opposition to renewed casino operations and the creation of a corporate body to manage Boracay. Kalibo Bishop Jose Corazon Tala-oc has added his voice to the resistance, saying gambling “foments a culture contrary to the demands of sound reason.” Etc.

Can the government hear the songs of angry men?