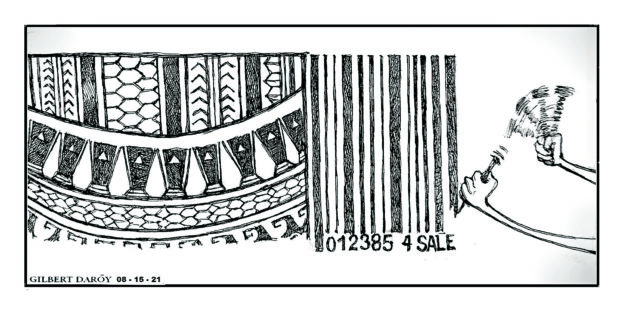

Creating a whirlwind of controversy over issues like cultural appropriation and the commercialization of traditional indigenous practices, the confrontation between supporters and spokespersons of Kalinga tattoo artist Whang-Od (or Whang-Ud), and Israeli vlogger Nuseir Yassin of Nas Daily, unwittingly became a highlight of the observance last Monday of the International Day of the World’s Indigenous Peoples.

A niece of Whang-Od claimed that deception and exploitation were employed when Nas Daily had the “mambabatok,” the traditional term for a creator of traditional tattoos, “sign” a contract (with her thumbprint) to make available tutorial sessions over the internet. For a fee of P750 per session, subscribers would be allowed to observe the 104-year-old National Living Treasure at work and presumably pick up the art and the craft of Kalinga tattooing.

“Learning it via clickable, paid content devalues batok (as the practice is called) and the people identified with the practice,” Analyn Salvador Amores, a professor of anthropology at UP-Baguio, wrote in this paper. The body marks were traditionally meant “to convey social status as well as political, religious, and social affiliation—a social biography of an individual.” But the tattoos have become individualized forms of self-expression ever since they captured the imagination of thrill seekers and tattoo lovers, so different from the original communal art and craft that was protected by a silent social contract among the Butbut, the tribe to which Whang-Od belongs.

Appropriating an indigenous tradition for purposes of profit is but one form of oppression that indigenous peoples (IPs) everywhere have had to put up with. Even deadlier is the systematic marginalization and exploitation of IPs by parties casting a moist eye on the natural resources on and underneath unexplored areas that have been proclaimed “ancestral domain.”

On the 23rd anniversary of the Indigenous Peoples Rights Act in October last year, Commission on Human Rights spokesperson Jacqueline de Guia called for revisiting the law that continues to be violated, often by state parties. De Guia said the CHR has seen “first-hand how IPs still endure abuse and other challenges” despite the existence of the law, and how “a lot of IPs still fall victim to land-related harassment, as businesses seek to take control of ancestral land for their own purposes.” Worse is how in some instances, “the problems stem from state enforcers themselves.”

Corollary to this harassment is the campaign against organized groups of IPs who are “Red-tagged” and accused of being members of the communist New People’s Army (NPA) or else as sympathizers if not supporters.

Just last month, two Aeta men, accused by the military of engaging in a firefight that left one soldier dead, were ordered released from jail. The two—Japer Gurung and Junior Ramos, the first to be charged under the Anti-Terrorism Act—said they had been tortured by the military. They were ordered released by an Olongapo court for the failure of the prosecution to identify the two as the perpetrators of the crime.

But that is but one victory in a series of attacks on IPs, often taking place in obscurity and isolation.

There was the violent operation last Dec. 30, 2020 that saw operatives of the Army, the police, and the Criminal Investigation and Detection Group swooping down on villages of Tapaz, Capiz and Calinog, Iloilo. When the dust settled, the police reported that nine people had died, while 17 were taken into custody. The targets were members of the Tumandok indigenous community who, authorities said, were suspected NPA, and those killed had resisted arrest.

But supporters of the Tumandok, including the local bishop, vehemently denied the accusation. The villagers, they said, were organizing to protest the construction of a dam that would have destroyed their ancestral lands.

Incidents like this have led Amnesty International to raise an alarm over what it called a “series of escalating attacks” against IPs. The organization has called on the government “to put a stop to violence, arrests, and harassment perpetrated against indigenous people,” and to “take concrete steps to ensure the protection, security, and well-being of all indigenous peoples, including those risking their lives to call attention to human rights violations in their communities and fight for indigenous peoples’ rights.”

IPs are under siege—from those who would exploit their ancestral art and culture for profit, to those eyeing the wanton exploitation of natural resources their communities safeguard, and those who see them as “other” and thus unworthy of respect, equality, or rights. It’s time to put deeper meaning and meaningful action to the work of protecting our indigenous peoples.