As the country grapples with record hunger and unprecedented economic difficulties in the shadow of the COVID-19 pandemic, it is now paying the price for its long neglect of the agriculture sector. Despite the country’s fertile soil and seas rich in resources, farmers and fisherfolk are still among its poorest, most marginalized citizens. Hunger, especially in the rural areas, is not only widespread but has worsened with the prolonged or recurring lockdowns, while bottlenecks and disruptions in the supply chain to urban centers have forced consumers to pay higher prices for their food.

From a big contributor to the growth of the Philippine economy, agriculture has declined markedly through the decades. Latest estimates of the Department of Agriculture showed that the farm sector would grow this year by 2-2.5 percent. Finance Secretary Carlos Dominguez III earlier said that agriculture must expand by at least 2.5 percent to keep up with the food demand of an increasing population. Over the past five years, however, agriculture grew by an average of only 0.9 percent. In the first quarter of this year, it even contracted by 3.3 percent due to the significant drop in the output of poultry and livestock.

Even before COVID-19 struck, the country was already in the grip of a food security crisis. According to a United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) report released in July 2020, the Philippines had the most number of food-insecure people in Southeast Asia from 2017 to 2019—some “59 million Filipinos suffering from moderate to severe lack of consistent access to food,” per a CNN dispatch on the UN data.

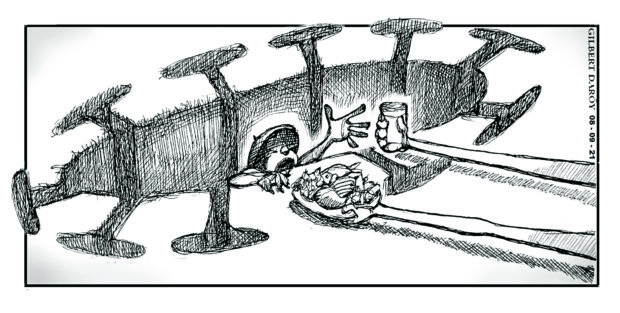

The pandemic since 2020 has only aggravated the problem. A study by several UN agencies released last week highlighted the need to ensure a reliable and functioning food supply in times of crisis, more so with Metro Manila and nearby provinces again going into lockdown. Part of the problem has to do with bringing farm produce to the market, especially to urban centers; there are not enough farm-to-market roads and transport facilities for agricultural products. The series of lockdowns since last year has, meanwhile, pushed many food producers to the brink of collapse.

With the closure of nonessential establishments in Metro Manila, thousands of jobs would be lost again, which is in turn expected to lower the demand for farm products. “Although our production is already low, the consumption and demand are much lower. In meat, we have an oversupply [that is being] worsened by the arrival of imports,” said United Broilers Raisers Association president Bong Inciong. “Everyone’s problem is demand because people don’t have the money to buy anymore.”

In their study “Assessing the Impact of COVID-19 on Food Systems and Adaptive Measures Practiced in Metro Manila,” the FAO, the United Nations Development Programme, the World Food Programme, and the International Fund for Agricultural Development noted how COVID-19 has caused severe disruptions to food markets and systems, directly affecting farming and fisheries workers.

These gaps, they warned, have resulted in considerable economic damage and food insecurity: “Small-scale food producers are considered less resilient to COVID-19 shocks, particularly in terms of restricted mobility and travel suspensions, due to farm operations requiring intensive labour, from planting, growing and harvesting to delivering farm produce.” Food supply and distribution, on the other hand, were hit by “disorganized and badly disrupted” supply chains due to restrictions on vehicle movement, depriving consumers of fresh and cheaper food sources.

A solution suggested by the UN agencies is for local government units to expand food security programs. Quezon City’s example could be emulated: It is supporting 166 urban farms within its jurisdiction to become stable food sources especially for the poor during the pandemic. Other LGUs must likewise develop local food spaces to make them less dependent on sources that are too far or too prone to disruptions.

Three months ago, former agriculture secretary Leonardo Montemayor wrote a comprehensive article on food security. Noting that farmers, food processors, traders, and consumers continued to face food security problems, he suggested that a summit be held on a common food security framework to bring stakeholders into a better understanding of the situation. That is a call certainly worth pursuing by the government. As the UN study highlighted, there is a need for a common understanding of the roles of the national and local governments in agricultural development and food governance—shared ground that is often missing at this time in their disparate and sometimes conflicting programs and projects meant to address the unyielding, elemental demand of adequate food for the people.