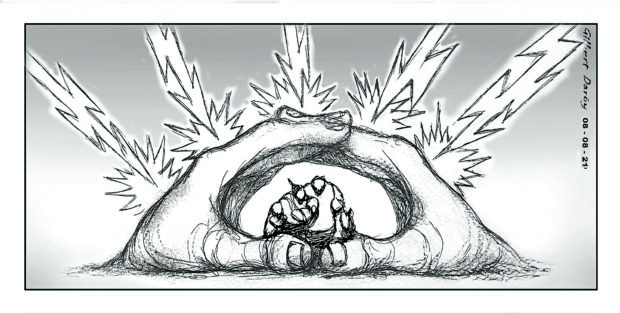

Enhanced by monsoon rains, Typhoon Fabian lashed the country last month and caused floods that resulted in the evacuation of more than 20,000 in the National Capital Region and other provinces. Amid the Fabian deluge, a 6.6-magnitude earthquake hit Calatagan, Batangas. While there was no damage reported from the tremor, these series of events were a reminder of the country’s vulnerability to natural calamities, complicated this time by the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

These are indeed no ordinary times to be dealing with natural disasters. “In the Philippines, COVID-19 is adding another layer of complexity in what is already a difficult year…” the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UN OCHA) said in a report in December last year. It noted how the country had to deal with a “triple crisis” in the last quarter of 2020: COVID-19 and two supertyphoons, “Rolly” and “Ulysses.” In between the two supertyphoons, tropical storms also affected the country, destroying property and agriculture and causing more misery to communities already fearful of the deadly virus.

On the average, the Philippines is visited by 20 typhoons a year (the weather bureau forecasts that two or three more typhoons will hit the country this month, and about 10 for the rest of the year), which makes evacuations in crowded shelters a recurring episode for many Filipinos. But with COVID-19 and its more contagious Delta variant, such situations where physical distancing, hygiene, sanitation, and proper ventilation are practically impossible could make things even worse for a health care system already overstretched.

The National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council recently issued a reminder referencing its memorandum last year that provided guidance on how to prepare for the rainy season amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Earlier, the Office of the Civil Defense (OCD) also emphasized the need for more localized preparedness and response efforts, reminding local government units (LGUs) to ensure stockpiles of food and non-food items, available facilities that could be used for quarantine, and evacuation plans catering to the specific needs of their constituents including persons with disabilities or comorbidities, the elderly, and pregnant women.

To be sure, there is no dearth of initiatives from both the public and private sectors in improving the country’s disaster management and response system. International humanitarian organization Care Philippines released last year a “contingency planning checklist,” containing recommendations to guide LGUs and other stakeholders in better managing risks and increasing response capacities in the face of pandemic-era typhoons and other disasters. Among its recommendations: ensuring food security and livelihood assistance to affected communities, as it noted that millions of Filipinos have lost their jobs due to the socioeconomic consequences of quarantine measures. “In some cases, aid is the only thing that separates families from hunger. The evolving needs of communities must be taken into consideration in the planning process to ensure relevance and appropriateness of assistance,” said the organization.

The Philippine Disaster Resilience Foundation (PDRF) also recently launched its Disaster Operations Center—the first ever in the region run by the private sector—that will integrate climate and disaster-related data. The PDRF, through this initiative, said it wants to bridge the lag time in the government’s response to any disaster as seen in previous calamities such as Typhoon “Yolanda.”

Last July 16, the Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology launched GeoMapperPH, a new web and mobile application designed to collate data on hazards, exposure, vulnerability, and coping capacity. Though limited to government entities and accredited nongovernment organizations for now, the database is envisioned to be helpful in providing crucial information on disasters and their immediate impact on specific locations.

As for individuals, the OCD has urged the public to prepare a “go bag” containing food packs, clothes, whistle, flashlight, batteries, and other important emergency items. Given the pandemic, however, the necessities must also include such items as disinfectant wipes and spray, bar or liquid soap, hand sanitizer with at least 60 percent alcohol, and multiple clean masks that should at least be two-ply.

All these public and private initiatives put together can help improve the country’s disaster response and protect Filipinos from hardships brought by calamities and exacerbated by the health crisis. As UN OCHA stated: “In the Philippines, a country with an average of 25 typhoons per year, 21 active volcanoes, and regular earthquake threats, addressing natural hazards requires a whole-of-society approach.”